A nineteenth century binnacle. Wikimedia

A nineteenth century binnacle. Wikimedia Roger McCoy

The magnetic compass is among those early world-altering inventions, which Daniel Boorstin identified as the clock, the compass, the printing press, the telescope, and the microscope. The compass used as a navigational tool was certainly the single most important development for world exploration. Despite its importance information on the origin of the compass is sketchy and its adoption was surprisingly slow. European and Asian mariners sailed the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean long before the compass was known and, even after its introduction, it often was used only as a last resort when other methods would not work. Navigation during this time relied on bottom soundings, stars, and written descriptions of currents, shoreline features, and bottom materials. A pilot’s guide might read in part, “…continue sailing until you find soundings of 100 fathoms depth, then veer toward the coast until you find 70 fathoms and a dark ooze, set a course toward the highest hill to reach the port.” After the invention of the compass specific bearings would be added, e.g. “…sail northwest by north until a 70 fathom bottom with a dark ooze is reached…”

During the early period of trade with Egypt, Syria, Turkey, India, and southeast Asia, Europeans knew almost nothing of China. This lack of knowledge about east Asia persisted despite a steady stream of spices, silks, and ceramics brought to Europe by caravan via the Silk Road through central Asia. The first major flow of information about China began when the Italian traveler, Marco Polo, went to China in 1271 and returned three and a half years later. His great contribution at that time was a book, The Description of the World, about his experiences and many observations throughout his trip. Amid the wealth of detail in his book is information about the use of a magnetic compass used by the Chinese for divination, but there is no mention that it was used for navigation. Also there is no evidence that he brought a compass back to Europe.

In Europe the magnetic compass was also used first for divination and later for navigation. Whether it came from China, which is likely, or was developed independently in Europe, the compass finally came into use for navigation in the Mediterranean region in the late thirteenth century.

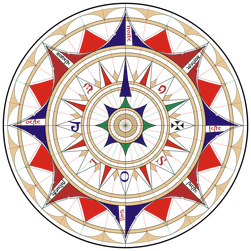

The Mediterranean Sea was already well-charted, with coastal outlines and wind roses to determine direction before the advent of the compass. The wind rose is the familiar direction indicator (see illustration) now considered synonymous with compass. But the wind rose was first aptly named as an indicator of the various wind directions.

The first magnetic compass was a lodestone, usually the mineral magnetite, that aligned itself in a north-south direction if allowed to move freely. An iron needle rubbed against a lodestone would acquire the same properties. The first application of this unexplained and mysterious phenomenon, whether in China or in Europe, was for divination. In China the compass was an important tool for feng shui, the art of maintaining harmony and alignment with nature. Only later was navigation added to the functions of the compass.

The first experiments in making a compass seems to have consisted of sticking a magnetized needle through a piece of straw so it would float on water. This worked in the stable conditions on land, but on a ship was not practical. The next stage was to balance the metal pointer on a pivot and place a wind rose underneath, with the north arrow aligned to the northern constellations. This began to make sense for actual navigation but needed one more improvement—a box, called a binnacle, to enclose the needle and protect it from disturbance by the wind. One last refinement was a candle inside the binnacle to make it visible at night. Eventually gimbals were added to keep the compass level during the pitching and rolling of the ship. All this development happened over a very short time, and the result was very similar to the compass seen on ships of more recent vintage. When iron ships appeared they added compensating magnets outside the binnacle to maintain proper north orientation.

The first known construction of a compass for navigation in Europe occurred in the city-state Amalfi, south of Naples, Italy. Although Amalfi has no significant port today, in 1300 A.D. it was the primary port in Italy. A monument in the city commemorates their claim to fame as the site of the invention of the navigation compass.

In the Mediterranean area the main effect of the compass for navigation was that ships could begin sailing throughout the year. By the end of the thirteenth century the compass was in common use in the Mediterranean and the practice of parking ships for the winter ended. Winter cloudiness was no longer a problem with the compass, and ships could make two or more trips each year between Venice or Genoa and Egypt and other ports in the Levant.

Then in the fifteenth century voyages turned more to the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean. The last decade of the fifteenth century was remarkable for the sudden urge to search for water routes to the Orient. The Portuguese began by gradually feeling their way down the coast of Africa, braving the unknown until they ultimately rounded the Cape of Good Hope and sailed into the Indian Ocean. The first to accomplish this feat and open an all-water route to India was Vasco de Gama in 1497. During the same period Columbus made three of his four voyages to the new world before 1500. John Cabot sailed from England to Newfoundland in 1497. Following those trailblazers inevitably one of them sailed around the world. Ferdinand Magellan was the first to circumnavigate beginning in 1519 but others followed. No one was satisfied they had found the shortest route to the Orient. There must be a passage somewhere and that thought kept exploration active well into the nineteenth century.

The role of the compass in all this new effort was paramount. The fact that all these voyages were in uncharted areas did not deter anyone. What gave them the confidence to go forth into such enormous spaces without a map or a guidebook was the compass. With the compass they knew they could keep track of their location and could eventually return to home port.

A new concern for mariners crossing the Atlantic was that the compass pointed to the west of the north stars. This variation was no problem in Europe where the magnetic deviation (variation from true north) is slight, but the farther west they traveled the more the compass pointed west of the stars. This alarming and unexplained situation at first caused disturbing doubts about the reliability of the compass. Many years passed before anyone knew that the north magnetic was not in the same location as the geographic north pole. Actually they had no understanding of Earth’s magnetism. The navigators compensated for this strange behavior by occasionally noting the difference between compass direction and north star direction and adjusting headings accordingly. For more detail on navigation refer to “Explorer’s Tales” posting on 5/28/2016.

Although much was known about celestial navigation by the fifteenth century, most mariners heading for open seas relied heavily on dead reckoning and the compass. Dead reckoning required a sand glass to measure the time elapsed on a particular course. Multiplying the time by their estimated speed a mariner could compute a distance traveled. A change of course required another estimate of distance, and all this information was carefully recorded on a map-in-the-making. The ultimate result was charts of all the continents and a great amassing of knowledge about the world.

Although the invention of the magnetic compass occurred in China, its world-changing application to exploration began in Italy. The well-known result was the discovery of the New World by European mariners.

Sources

Aczel, Amir D. The riddle of the compass. Harcourt, Inc: New York. 2001.

Gurney, Alan. Compass, A story of exploration and innovation. New York: W.W. Norton. 2004.

Boorstin, Daniel J. Cleopatra’s nose: Essays on the unexpected. New York: Vintage Books. 1994.

May, William E. A History of Marine Navigation, Henley-on Thames: G. T. Foulis and Co., 1973.

Taylor, E. G. R. The Haven Finding Art: A History of Navigation from Odysseus to Captain Cook. London: Abelard - Schuman, Ltd, 1957.

Waters, David. The Art of Navigation in Elizabethan and Early Stuart Times. Greenwich, England: National Maritime Museum, 1978.

The magnetic compass is among those early world-altering inventions, which Daniel Boorstin identified as the clock, the compass, the printing press, the telescope, and the microscope. The compass used as a navigational tool was certainly the single most important development for world exploration. Despite its importance information on the origin of the compass is sketchy and its adoption was surprisingly slow. European and Asian mariners sailed the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean long before the compass was known and, even after its introduction, it often was used only as a last resort when other methods would not work. Navigation during this time relied on bottom soundings, stars, and written descriptions of currents, shoreline features, and bottom materials. A pilot’s guide might read in part, “…continue sailing until you find soundings of 100 fathoms depth, then veer toward the coast until you find 70 fathoms and a dark ooze, set a course toward the highest hill to reach the port.” After the invention of the compass specific bearings would be added, e.g. “…sail northwest by north until a 70 fathom bottom with a dark ooze is reached…”

During the early period of trade with Egypt, Syria, Turkey, India, and southeast Asia, Europeans knew almost nothing of China. This lack of knowledge about east Asia persisted despite a steady stream of spices, silks, and ceramics brought to Europe by caravan via the Silk Road through central Asia. The first major flow of information about China began when the Italian traveler, Marco Polo, went to China in 1271 and returned three and a half years later. His great contribution at that time was a book, The Description of the World, about his experiences and many observations throughout his trip. Amid the wealth of detail in his book is information about the use of a magnetic compass used by the Chinese for divination, but there is no mention that it was used for navigation. Also there is no evidence that he brought a compass back to Europe.

In Europe the magnetic compass was also used first for divination and later for navigation. Whether it came from China, which is likely, or was developed independently in Europe, the compass finally came into use for navigation in the Mediterranean region in the late thirteenth century.

The Mediterranean Sea was already well-charted, with coastal outlines and wind roses to determine direction before the advent of the compass. The wind rose is the familiar direction indicator (see illustration) now considered synonymous with compass. But the wind rose was first aptly named as an indicator of the various wind directions.

The first magnetic compass was a lodestone, usually the mineral magnetite, that aligned itself in a north-south direction if allowed to move freely. An iron needle rubbed against a lodestone would acquire the same properties. The first application of this unexplained and mysterious phenomenon, whether in China or in Europe, was for divination. In China the compass was an important tool for feng shui, the art of maintaining harmony and alignment with nature. Only later was navigation added to the functions of the compass.

The first experiments in making a compass seems to have consisted of sticking a magnetized needle through a piece of straw so it would float on water. This worked in the stable conditions on land, but on a ship was not practical. The next stage was to balance the metal pointer on a pivot and place a wind rose underneath, with the north arrow aligned to the northern constellations. This began to make sense for actual navigation but needed one more improvement—a box, called a binnacle, to enclose the needle and protect it from disturbance by the wind. One last refinement was a candle inside the binnacle to make it visible at night. Eventually gimbals were added to keep the compass level during the pitching and rolling of the ship. All this development happened over a very short time, and the result was very similar to the compass seen on ships of more recent vintage. When iron ships appeared they added compensating magnets outside the binnacle to maintain proper north orientation.

The first known construction of a compass for navigation in Europe occurred in the city-state Amalfi, south of Naples, Italy. Although Amalfi has no significant port today, in 1300 A.D. it was the primary port in Italy. A monument in the city commemorates their claim to fame as the site of the invention of the navigation compass.

In the Mediterranean area the main effect of the compass for navigation was that ships could begin sailing throughout the year. By the end of the thirteenth century the compass was in common use in the Mediterranean and the practice of parking ships for the winter ended. Winter cloudiness was no longer a problem with the compass, and ships could make two or more trips each year between Venice or Genoa and Egypt and other ports in the Levant.

Then in the fifteenth century voyages turned more to the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean. The last decade of the fifteenth century was remarkable for the sudden urge to search for water routes to the Orient. The Portuguese began by gradually feeling their way down the coast of Africa, braving the unknown until they ultimately rounded the Cape of Good Hope and sailed into the Indian Ocean. The first to accomplish this feat and open an all-water route to India was Vasco de Gama in 1497. During the same period Columbus made three of his four voyages to the new world before 1500. John Cabot sailed from England to Newfoundland in 1497. Following those trailblazers inevitably one of them sailed around the world. Ferdinand Magellan was the first to circumnavigate beginning in 1519 but others followed. No one was satisfied they had found the shortest route to the Orient. There must be a passage somewhere and that thought kept exploration active well into the nineteenth century.

The role of the compass in all this new effort was paramount. The fact that all these voyages were in uncharted areas did not deter anyone. What gave them the confidence to go forth into such enormous spaces without a map or a guidebook was the compass. With the compass they knew they could keep track of their location and could eventually return to home port.

A new concern for mariners crossing the Atlantic was that the compass pointed to the west of the north stars. This variation was no problem in Europe where the magnetic deviation (variation from true north) is slight, but the farther west they traveled the more the compass pointed west of the stars. This alarming and unexplained situation at first caused disturbing doubts about the reliability of the compass. Many years passed before anyone knew that the north magnetic was not in the same location as the geographic north pole. Actually they had no understanding of Earth’s magnetism. The navigators compensated for this strange behavior by occasionally noting the difference between compass direction and north star direction and adjusting headings accordingly. For more detail on navigation refer to “Explorer’s Tales” posting on 5/28/2016.

Although much was known about celestial navigation by the fifteenth century, most mariners heading for open seas relied heavily on dead reckoning and the compass. Dead reckoning required a sand glass to measure the time elapsed on a particular course. Multiplying the time by their estimated speed a mariner could compute a distance traveled. A change of course required another estimate of distance, and all this information was carefully recorded on a map-in-the-making. The ultimate result was charts of all the continents and a great amassing of knowledge about the world.

Although the invention of the magnetic compass occurred in China, its world-changing application to exploration began in Italy. The well-known result was the discovery of the New World by European mariners.

Sources

Aczel, Amir D. The riddle of the compass. Harcourt, Inc: New York. 2001.

Gurney, Alan. Compass, A story of exploration and innovation. New York: W.W. Norton. 2004.

Boorstin, Daniel J. Cleopatra’s nose: Essays on the unexpected. New York: Vintage Books. 1994.

May, William E. A History of Marine Navigation, Henley-on Thames: G. T. Foulis and Co., 1973.

Taylor, E. G. R. The Haven Finding Art: A History of Navigation from Odysseus to Captain Cook. London: Abelard - Schuman, Ltd, 1957.

Waters, David. The Art of Navigation in Elizabethan and Early Stuart Times. Greenwich, England: National Maritime Museum, 1978.