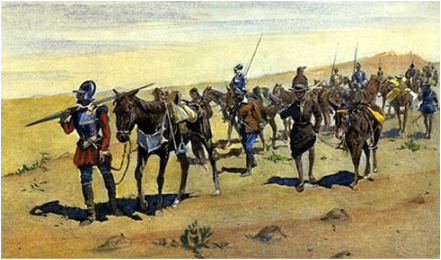

Coronado's Trek. Artist, F. Remington

Coronado's Trek. Artist, F. Remington Visions of wealth pulled many explorers beyond the horizon to the New World. Although they initially sought new trade routes to Asia, they soon saw the potential for wealth in the two new and unknown continents standing in the way. Much of their search for wealth in the New World often had no basis in fact so they relied on some variation of the following myths.

Cities of Gold

The notion that cities of gold existed on islands far to the west of Europe began in classical antiquity with the lost island of Atlantis. In the late middle ages the imaginary island of Antillia was believed to have seven cities of gold established by seven Christian bishops who fled the Islamic invasions that began in the year 712. Maps placed the island of Antillia in the middle of the Atlantic until ships began to sail routinely through the supposed location without finding it. This discrepancy did not kill the myth but merely moved the presumed location farther west to the islands near North America. Around the middle of the sixteenth century the search for Antillia ended but the notion of seven cities of gold was reborn and relocated in the interior of North America. The name Antillia was forgotten except for the group of Caribbean islands called the Antilles.

The idea that seven cities of gold were waiting to be found was too good to die and the myth reemerged as the golden cities of Cibola in present day northwest New Mexico and Quivira somewhere in Kansas. Cabeza de Vaca and the slave Esteban (Explorer’s Tales, 6/13/2015) reported that the Indians told them of these far-away cities of gold. No one knows what the Indians actually told them or what motives the Indians may have had. Also no one knows exactly what questions the Europeans asked to elicit such responses. Explorers in the Arctic learned that the Inuits often gave answers they thought the Europeans wanted to hear. I assume the same cultural trait may have induced the Indians to tell the Spaniards about cities of gold. On the other hand, maybe the Indians just wanted to get rid of the intruders by sending them away.

In 1540 Francisco Coronado began a search for these cities and upon reaching what he thought was Quivira, wrote, "The province of Quivira is 950 leagues from Mexico. Where I reached it is in the 40th degree. The country itself is the best I have ever seen for producing all the products of Spain, for besides the land itself being very fat and black and being well watered by the rivulets and springs and rivers, I found prunes like those of Spain, and nuts, and very good sweet grapes and mulberries. I had been told that the houses were made of stone and were several storied; they are only of straw, and the inhabitants are as savage as any that I have seen.” (“In the 40th degree” could imply between 39˚ and 40˚. The north border of Kansas is 40˚.)

Coronado learned a lot about southwest North America, but found no wealth whatsoever. As a result New Spain ignored its vast northern lands and eventually lost them.

In the Amazon basin of South America another supposed city of gold eluded discovery by the Spanish as well as the English. One searcher was Gonzalo Pizarro, half-brother of Francisco Pizarro who conquered the Incas. He was drawn by the story of a tribe high in the Andes mountains in what is now Colombia. When a new chieftain rose to power his rule began with a ceremony at Lake Guatavita. Accounts consistently say the new ruler was covered with gold dust and that golden objects and precious jewels were thrown into the lake to appease a god that lived underwater. This gold-covered chieftain was call El Dorado (The Gilded One). Later the name was applied to the place where he lived. Spaniards and other Europeans had found so much gold among the natives along the South American continent's northern coast that they understandably believed there had to be a place of great wealth somewhere in the interior. The Spaniards found Lake Guatavita in1545 and tried to drain it. They lowered its level enough to find hundreds of gold items along the lake's edge. This discovery supported the story of gold in the lake, but no city of El Dorado was found.

Sir Walter Raleigh made two trips to Guiana to search for El Dorado. During his second trip in 1617 he sent his son, Watt Raleigh, with an expedition up the Orinoco River. But Walter Raleigh, then an old man, stayed behind at a base camp on the island of Trinidad. The expedition was a disaster, and Watt Raleigh was killed in a battle with Spaniards. Raleigh returned to England, where King James the First ordered him beheaded for, among other things, disobeying orders to avoid conflict with the Spanish.

Mountains of Silver

The Sierra de la Plata (Silver Mountains) was a mythical source of silver in the interior of South America. The legend began in the early 16th century when shipwrecked sailors heard stories of a mountain of silver in an inland region. The first European to lead an expedition in search of it was Aleixo Garcia, who crossed almost the entire continent to reach the Andean altiplano. Survivors of that ill-fated expedition brought some precious metals back with them, but future expeditions ended in failure. Place names such as Argentina, from the Latin word for silver, argentum, and Rio de la Plata (River of Silver) are reminders of the mountain of silver myth.

The Strait of Anián

After Magellan’s ships returned in 1522 it was established that an end run could be made at the far south end of the huge land mass. Cosmographers generally thought the Earth was created with balance and symmetry. Therefore logically there must be a passage in the northern hemisphere as well. The belief in a passage led cartographers to insert a passage on their maps for the simple reason that it should exist. They even named it the Strait of Anián, yet it eluded all searchers. However failure to find such a passage did not prove it did not exist—there was always another inlet or bay that might have been overlooked. This was myth with a grain of truth, but based largely on faulty science and creative cartography.

The name Anián, first documented around 1560, probably took its name from Ania, a Chinese province mentioned in a 1559 edition of Marco Polo’s book. The imaginary strait was variously mapped extending from Hudson Bay to one of several different bays on the west coast ranging from San Diego to Cook’s Inlet in Alaska.

Three expeditions In the eighteenth century conclusively disproved the existence of the Strait of Anián. Samuel Hearne traveled overland in 1770 from Hudson Bay to the Arctic Ocean without encountering a water passage (Explorer’s Tales, 9/15/2014). Alexander MacKenzie had the same result on a trip from south to north across Canada in 1789 (Explorer’s Tales, 3/15/2015). Captain James Cook sailed up the west coast of North America in 1776 -79 investigating many sites, including Cook’s Inlet. Cook’s voyage continued to Hawaii where he lost his life in a skirmish with natives (Explorer’s Tales, 8/1/2014). Despite the supposed death of the Strait of Anián myth, it continued into the nineteenth century before its final demise.

Eventually a northern water passage was found, but much of it was locked in ice even in the summer. This Arctic passage was not traversed until 1906 by Roald Amundsen, more than 400 years after the search began. The cosmographers’ certainty of a northern passage was correct, but for the wrong reasons.

Fountain of Youth

The myth of a fountain of youth existed for at least 2000 of years, first appearing in the fifth century BCE. Ponce de Leon is often believed to have sought the Fountain of Youth on his fatal expedition to Florida, but scholars have found no evidence in his writings that his objective was youth restoring waters. One historian suggests that a member of the Spanish court may have introduced the idea of the Fountain of Youth as a political maneuver to discredit Ponce de Leon. Courtier Gonzalo Oviedo described Ponce as a gullible, foolish, and dull-witted man who was trying to find waters to restore his youth. Even in the sixteenth century this was considered a silly idea. This popular myth appears not to have been a motive for exploration even though we may have learned otherwise.

Myths were often used to sell an exploration project to investors who could be hooked by the idea of sudden wealth. Investors could imagine great returns, and explorers could expect fortune, fame, and political power. Myths survived simply because they sounded plausible, and men passionately wanted them to be true. In the end, however, they went the way of all things that sound too good to be true.

References

Drye, W. El Dorado legend snares Sir Walter Raleigh. National Geographic (no date given). retrieved from science.nationalgeographic.com/science/archaeology/el-dorado/

Gough, Barry M. Strait of Anian. Canadian encyclopedia, February, 2006. retrieved from www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/strait-of-anian/

Preston, Douglas. Cities of Gold: A journey across the American southwest. University of New Mexico Press, 1999.

Shaer, Matthew. Ponce de Leon never searched for the Fountain of Youth. Smithsonian Magazine, June, 2013.