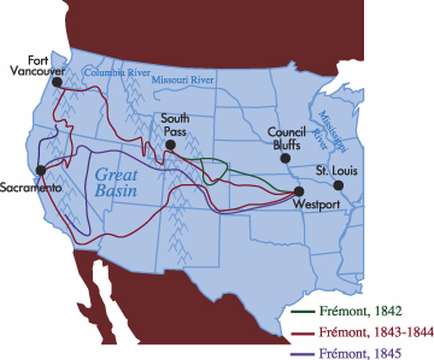

First three Fremont expeditions.

First three Fremont expeditions. Roger M McCoy

Although the Lewis and Clark expedition had explored a portion of the vast interior of North America by 1806, there was still much unexplored land between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Ocean. A strong feeling existed among many Americans that all that land should be part of the United States although much of it belonged to Mexico. Some people were already considering a move into the west even though so little was known. To this end the U.S. Government began a series of western surveys to establish possible routes, inventory resources, and most of all maintain a presence in the Louisiana Purchase lands, and even the lands still owned by Mexico.

Five such surveys from 1842 to 1854 were led by an army officer named John C. Frémont. Between surveys Frémont served as Military Governor of California (before statehood) and a very short term as one of the two first senators from California (after statehood in 1850). After the surveys Frémont became the first presidential candidate for the newly formed Republican Party but lost to James Buchanan in 1856. He was a man of many parts involved in politics, land acquisitions, and gold mining, but our focus for the moment is his exploration surveys.

In 1842 Frémont met Kit Carson, a well-known frontiersman, and arranged for him to act as guide on the first expedition. Also on that expedition was a dour German cartographer, Charles Preuss, who made no secret of the fact that he hated the wilderness but he went with Frémont repeatedly. Frémont and twenty-five men journeyed for five months exploring the land between Missouri and the Rocky Mountains. A few excerpts of journals written during that first trip show a remarkable difference between the enthusiastIc Frémont and the morose Preuss, who obviously had little respect for Fremont.

Near the site of present day Manhattan, Kansas, Frémont wrote of the beautiful prairies and streams. People in Kansas today will readily verify his description of the beauty of the land and the intensity of its storms.

June 22,1842. Our route the next morning lay up the valley, which bordered by hills and graceful slopes looked uncommonly beautiful. The stream [the Little Blue] was about fifty feet wide and three or four feet deep, fringed by cottonwood and willow with frequent groves of oak tenanted by wild turkeys. Elk were frequently seen in the hills and now and then an antelope bounded across our path or a deer broke from the groves.

After thirty-one miles a heavy bank of black clouds in the west came on us in a storm preceded by a violent wind. The rain fell in such torrents that it was difficult to breathe facing the wind, the whole sky was tremulous with lightning; now and then illuminated by a blinding flash, succeeded by pitchy darkness.

Charles Preuss during that same period of the trip wrote:

June 6, 1842. Annoyed by that childish Frémont. During the night a lot of rain, which made me get up; everything wet. What a disorder in this outfit. To be sure, how can a foolish lieutenant [Frémont] manage such a thing?

June 12, 1842. A lot of rain at night; slept in a poor tent.

Eternal prairie and grass with occasional groups of trees. Frémont prefers this to every other landscape. To me it is as if someone would prefer a book with blank pages to a good story. The ocean has its storms and icebergs, the beautiful sunrise and sunset. But the prairie? To the deuce with such a life.

June 19, 1842. Our big chronometer has gone to sleep. That is what always happens when the egg wants to be wiser than the hen. So far I can’t say that I have formed a very high opinion of Frémont’s astronomical manipulations. Now he has started to botanize.

Had a remarkably bad night. First came a thunderstorm with torrential rain which drenched us thoroughly in our miserable tents. Then it became so warm that the mosquitoes were as if possessed by the devil, and I could not sleep a minute. The others lay safely under their nets; mine had been forgotten because of Frémont’s negligence.

Preuss would be surprised to know that many plants of the west have fremontii as their species or sub-species name today because Frémont first collected them. One well-known example is the southwestern cottonwood tree, Populus fremontii.

At the end of the first expedition Frémont wrote an account of the expedition titled, A Report on an Exploration of the Country Lying between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains on the Line of the Kansas and Great Platte Rivers. This report became very popular reading and was reproduced in newspapers across the country. The public became captivated with the vision of the west as an inviting land beckoning to be settled. Frémont was an instant celebrity and an enthusiastic promoter of westward movement much to the satisfaction of his expansionist father-in-law, Senator Thomas Hart Benton, uncle of the American artist by the same name. Frémont's success led to a second expedition the following summer.

The second expedition in 1843 again included Kit Carson as well as Charles Preuss, who continued to produce excellent topographic maps of all terrain they passed through. Their route took them along the Snake River to the Columbia River into Oregon—a route that became the Oregon Trail. They reached the Cascade Mountains, turned south into California, and became the first to see and describe Lake Tahoe, then turned west to the site of Sacramento. The published report and map from this expedition became a guide for thousands of immigrants who came to Oregon and California.

The third expedition in 1845 filled in a major void in the Great Basin of Utah and Nevada. The cumulative effect of these first three surveys of the west was to establish routes that became known as the Oregon Trail, California Trail through Nevada and across the Sierra Mountains (think Donner party), and the Applegate Trail from Oregon south to California.

Frémont certainly became famous for his expeditions and an admired public figure. But no praise was higher than that of his companion Kit Carson. Carson came to admire Frémont for his success with his own men on the expeditions. Carson wrote,

I was with Frémont from 1842 to 1847. The hardships through which we passed I find impossible to describe, and the credit which he deserves I am incapable of doing justice in writing. I can never forget his treatment of me when in his employ and how cheerfully he suffered with his men while undergoing the severest hardships. His perseverance and willingness to participate in all that was undertaken, no matter whether the duty was rough or easy, is the main cause of his success. And I say without fear of contradiction that none but him could have surmounted and succeeded through as many difficult services as his was.

Sources

Egan, Ferol. Frémont: Explorer for a Restless Nation. Reno: University of Nevada Press. 1977.

Bergon, F. and Papanikolas, Z., eds. Looking Far West: The Search For The American West. New York: The New American Library. 1978