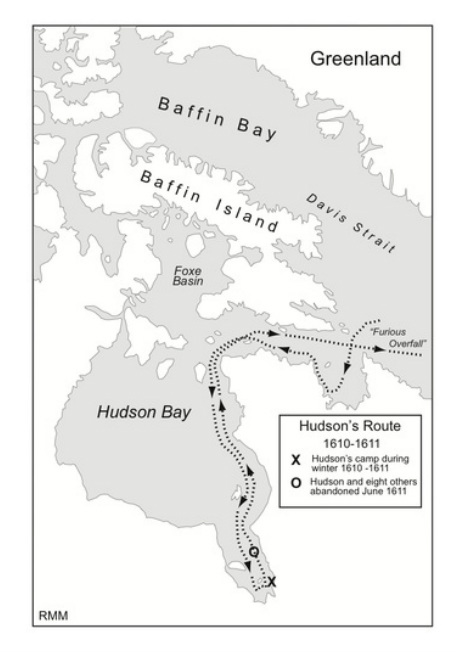

Route of Hudson's fourth voyage.

Route of Hudson's fourth voyage. Roger M. McCoy

After his voyage to New York Bay in 1609 and having claimed that area for the Dutch, Henry Hudson was prohibited by the king of England from sailing again for a foreign country. In a few months, however, he again had the attention of investors and King James I. Hudson no doubt learned quickly that success often depends on saying what people most want to hear, and what they wanted to hear was the possibility of a water passage through the American continent.

Hudson had knowledge of a “furious overfall” near latitude 60˚N that had been reported by explorer John Davis in 1587. Some evidence suggests that Hudson had been with Davis on that voyage. What they had seen was a strong turbulence in mid-ocean. Such a disturbance often indicates the presence of a current strong enough to make standing waves, whereas normal waves in the ocean are typically traveling. Hudson surmised that the current was a powerful tidal flow from a far western ocean through a narrow opening into the Davis Strait arm of the Atlantic Ocean. He concluded that he had only to sail through this “furious overfall,” through the narrow opening, and into the “Oriental Sea.” That was the hook that sold the deal. In fact, the tidal flow was coming from Hudson Bay, which happens to be big enough to produce a tidal flow through Hudson Strait.

By June of 1610 Hudson’s craft, the Discovery, arrived at the “furious overfall” and proceeded westward through a strait (Hudson Strait) against a current beset with ice floes and icebergs. Arctic sailing was unfamiliar and frightening to the crew, especially after seeing the dangerous wave produced when an iceberg suddenly toppled nearby. At the west end of the strait they entered the expanse of water that is now called Hudson Bay. Hudson estimated their longitude and determined they had sailed farther west into this new continent than any previous European.

By now some of the crew had had enough of the Arctic and wanted to head home. Sensing discontent among the crew and fear of the hazards of sailing among ice floes and icebergs, Hudson asked if they wanted to proceed farther. This democratic gesture was unusual for a ship’s captain then... as it would be today.. Despite some men wanting to turn around, Hudson decided to continue as planned.

At this time they stopped to go ashore on the treeless tundra where they gathered an abundance of “scurvy grass” and sorrel, both known at that time to prevent scurvy. Scurvy grass is not actually a grass, but is a low growing plant of the cabbage family, now known to be rich in vitamin C. They turned southward along the east coast of the bay and eventually came to an embayment now called James Bay. It soon became clear that they had reached a dead end. Hudson sailed the Discovery around the small embayment, and would not leave it, even long after it became clear that no passage existed in the area.

To understand what happened aboard the Discovery, it is necessary to look into the complicated character of three principal men; Henry Hudson, Robert Juet, and Henry Greene.

Robert Juet had sailed previously with Hudson as first mate and was a skilled navigator. Juet was a source of unrest among the crew by making disparaging remarks about Hudson’s competence. He predicted at the very beginning of the voyage that bloodshed and violence would probably occur. His steady forceful complaining combined with his higher rank made him a significant source of discord among the crew.

Henry Greene was a last minute addition to the crew and is believed to have had some prior association with Hudson. He proved to be a disagreeable young man whom the crew quickly came to dislike. They even suspected, at Juet’s suggestion, that Greene was put on board by Hudson to spy on the rest of the crew.

On one occasion Hudson showed favoritism toward Greene following the death of a crewman, by decreeing that a part of the dead man’s garments should go to Greene, rather than be auctioned as was customary. Later Hudson had an altercation with the ship’s carpenter who refused to build a shelter on shore for the winter. Later when the carpenter went ashore to hunt, Greene went with him. Hudson considered Greene’s association with the belligerent carpenter to be disloyal and reneged on giving him the dead man’s garment. Greene reacted badly to this switch and became vehement himself in stirring discontent among the rest of the crew.

Hudson tolerated these two trouble makers with a stern warning and agreed not to punish them if they would stop creating unrest. For a ship’s captain, he seemed to be remarkably indecisive and lenient to troublemakers. These traits gave the impression of incompetence and poor leadership to crewmen accustomed to captains in firm control with swift punishment for wrongdoing. Hudson did replace Juet with Robert Bylot as first mate, but allowed Juet to stay on deck as an ordinary seaman, rather than removing him to some place of confinement below decks. Juet was angered by this demotion, and continued to be a negative influence on the crew.

For no apparent reason Hudson kept the Discovery in James Bay long after determining there was no passage. By November ice had begun to form in James Bay, making the ship immobile. The voyage had begun in May with enough provisions to last through November, which means that they intended to be home by that time. They had supplemented the food supply by hunting the thousands of ptarmigans and an abundance of fish. But now the birds had migrated and ice prevented fishing. The ship would be icebound until late spring, and the remaining provisions must be stretched to last. Not surprisingly, this dangerous situation put the crew in an unhappy state.

They all made it through the winter without starvation, and their stockpile of scurvy grass prevented that debilitating and deadly scourge. Hudson distributed the last of the food, which consisted mainly of bread and cheese. At one point, Hudson was convinced that some men were hoarding food, and ordered a search of men’s personal sea chests. Although he found some bread, his action further incensed the men. Ice began to open up in early June, and the men later claimed that Hudson still was showing no inclination to begin the voyage home. Thus began a series of events that led to one of the most dastardly deeds that can befall a ship’s captain: mutiny.

After his voyage to New York Bay in 1609 and having claimed that area for the Dutch, Henry Hudson was prohibited by the king of England from sailing again for a foreign country. In a few months, however, he again had the attention of investors and King James I. Hudson no doubt learned quickly that success often depends on saying what people most want to hear, and what they wanted to hear was the possibility of a water passage through the American continent.

Hudson had knowledge of a “furious overfall” near latitude 60˚N that had been reported by explorer John Davis in 1587. Some evidence suggests that Hudson had been with Davis on that voyage. What they had seen was a strong turbulence in mid-ocean. Such a disturbance often indicates the presence of a current strong enough to make standing waves, whereas normal waves in the ocean are typically traveling. Hudson surmised that the current was a powerful tidal flow from a far western ocean through a narrow opening into the Davis Strait arm of the Atlantic Ocean. He concluded that he had only to sail through this “furious overfall,” through the narrow opening, and into the “Oriental Sea.” That was the hook that sold the deal. In fact, the tidal flow was coming from Hudson Bay, which happens to be big enough to produce a tidal flow through Hudson Strait.

By June of 1610 Hudson’s craft, the Discovery, arrived at the “furious overfall” and proceeded westward through a strait (Hudson Strait) against a current beset with ice floes and icebergs. Arctic sailing was unfamiliar and frightening to the crew, especially after seeing the dangerous wave produced when an iceberg suddenly toppled nearby. At the west end of the strait they entered the expanse of water that is now called Hudson Bay. Hudson estimated their longitude and determined they had sailed farther west into this new continent than any previous European.

By now some of the crew had had enough of the Arctic and wanted to head home. Sensing discontent among the crew and fear of the hazards of sailing among ice floes and icebergs, Hudson asked if they wanted to proceed farther. This democratic gesture was unusual for a ship’s captain then... as it would be today.. Despite some men wanting to turn around, Hudson decided to continue as planned.

At this time they stopped to go ashore on the treeless tundra where they gathered an abundance of “scurvy grass” and sorrel, both known at that time to prevent scurvy. Scurvy grass is not actually a grass, but is a low growing plant of the cabbage family, now known to be rich in vitamin C. They turned southward along the east coast of the bay and eventually came to an embayment now called James Bay. It soon became clear that they had reached a dead end. Hudson sailed the Discovery around the small embayment, and would not leave it, even long after it became clear that no passage existed in the area.

To understand what happened aboard the Discovery, it is necessary to look into the complicated character of three principal men; Henry Hudson, Robert Juet, and Henry Greene.

Robert Juet had sailed previously with Hudson as first mate and was a skilled navigator. Juet was a source of unrest among the crew by making disparaging remarks about Hudson’s competence. He predicted at the very beginning of the voyage that bloodshed and violence would probably occur. His steady forceful complaining combined with his higher rank made him a significant source of discord among the crew.

Henry Greene was a last minute addition to the crew and is believed to have had some prior association with Hudson. He proved to be a disagreeable young man whom the crew quickly came to dislike. They even suspected, at Juet’s suggestion, that Greene was put on board by Hudson to spy on the rest of the crew.

On one occasion Hudson showed favoritism toward Greene following the death of a crewman, by decreeing that a part of the dead man’s garments should go to Greene, rather than be auctioned as was customary. Later Hudson had an altercation with the ship’s carpenter who refused to build a shelter on shore for the winter. Later when the carpenter went ashore to hunt, Greene went with him. Hudson considered Greene’s association with the belligerent carpenter to be disloyal and reneged on giving him the dead man’s garment. Greene reacted badly to this switch and became vehement himself in stirring discontent among the rest of the crew.

Hudson tolerated these two trouble makers with a stern warning and agreed not to punish them if they would stop creating unrest. For a ship’s captain, he seemed to be remarkably indecisive and lenient to troublemakers. These traits gave the impression of incompetence and poor leadership to crewmen accustomed to captains in firm control with swift punishment for wrongdoing. Hudson did replace Juet with Robert Bylot as first mate, but allowed Juet to stay on deck as an ordinary seaman, rather than removing him to some place of confinement below decks. Juet was angered by this demotion, and continued to be a negative influence on the crew.

For no apparent reason Hudson kept the Discovery in James Bay long after determining there was no passage. By November ice had begun to form in James Bay, making the ship immobile. The voyage had begun in May with enough provisions to last through November, which means that they intended to be home by that time. They had supplemented the food supply by hunting the thousands of ptarmigans and an abundance of fish. But now the birds had migrated and ice prevented fishing. The ship would be icebound until late spring, and the remaining provisions must be stretched to last. Not surprisingly, this dangerous situation put the crew in an unhappy state.

They all made it through the winter without starvation, and their stockpile of scurvy grass prevented that debilitating and deadly scourge. Hudson distributed the last of the food, which consisted mainly of bread and cheese. At one point, Hudson was convinced that some men were hoarding food, and ordered a search of men’s personal sea chests. Although he found some bread, his action further incensed the men. Ice began to open up in early June, and the men later claimed that Hudson still was showing no inclination to begin the voyage home. Thus began a series of events that led to one of the most dastardly deeds that can befall a ship’s captain: mutiny.