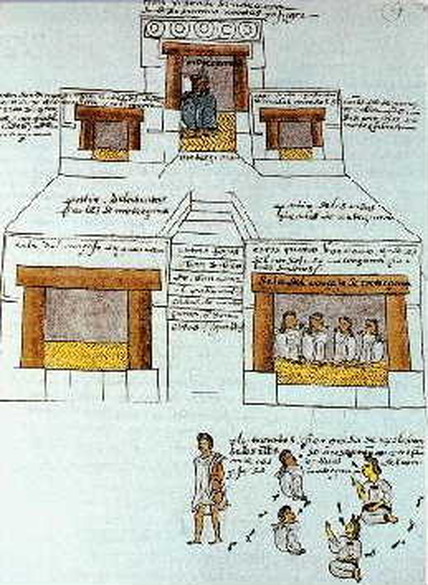

Montezuma's Palace. Mendoza, 1542. Wikipedia

Montezuma's Palace. Mendoza, 1542. Wikipedia Roger M. McCoy

During the fifty years after discovery of the New World, Spain’s empire grew to an area larger than the Romans had acquired in 500 years. First the Spanish established colonies on major islands in the Caribbean, i.e., Hispaniola, Cuba, Jamaica. They then explored the gulf coast and the coast of Central America searching for a through passage...to no avail. Balboa crossed the isthmus, sighted, and claimed the Pacific Ocean. Ponce de Leon explored and died in Florida, and the east coast of South America was explored as far south as the Rio de la Plata, now Argentina. Trade of gold ornaments from Indians along the coast of Central America suggested great riches in the interior of these lands, and the inland exploration movement began. The smell of gold induced the viceroy of Cuba to select a promising young man who had helped conquer Cuba as the one who should push into the unknown lands of Mexico, so in 1518 Hernán Cortés undertook the conquest.

This effort was so shockingly easy for 600 soldiers, fifteen horsemen, and fifteen cannon that it is considered nothing short of miraculous. If you recall the story of Kipling’s The Man Who Would be King, you will have some idea of the strategy Cortés followed. He started with only a minimal force of trained, well-armed soldiers and pressed his defeated foes to join the fight against the next enemy. The army grew larger as they conquered successive cities and eventually the cities simply received the Spaniards with no resistance.

This rapid success came partly by force in the beginning, but by the time Cortés and his army reached Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Aztec empire and the largest city in the Americas, cultural factors gave a decided edge to the Spanish. The Europeans brought a combination of things unknown to the Aztecs: horses were totally new and thought to be godly; the Spaniard’s gleaming armor and their noisy, harquebuses were terrifying. These sights alone were enough to convince the Aztecs that these strangers were children of the Sun God. These unusual items however were only a part of the Spanish advantage over the Aztecs. It helped that the Aztec religious culture was already anticipating a major change in the near future.

Bernal Díaz, who was with Cortés, wrote, “As a result of our victories, which God granted us, our fame spread through the surrounding country and reached the ears of the great Montezuma. When the news came that so few of us had conquered such a huge force, terror spread through the whole land.” Montezuma soon sent emissaries to negotiate an annual tribute of gold. The emissaries told Cortés that Montezuma merely wanted to save them the hardships of crossing a “rough and sterile” land to reach the capital city. Cortés ignored their pleas and forged ahead to the riches.

Cortés entered the capital city, which Bernal Díaz calls Mexico, accompanied by three powerful caciques (chieftains) through streets crowded with people from far away who came to see the unknown spectacle of horses and strange light-skinned men. Montezuma sent men to greet Cortés and “as a sign of peace they touched the ground with their hands and kissed it.”

When Cortés met Montezuma he proceeded to give a speech about “how we are all brothers, the children of one mother and father called Adam and Eve; and how a brother, our great Emperor, grieved for the perdition of so many souls and sent us to tell him this that they might give up the worship of idols and taking human sacrifices.”

Surprisingly, Montezuma’s reply was that he was already familiar with much that Cortés was telling him. He said, “Regarding the creation of the world, we have held the same belief for many ages, and are certain you are those who our ancestors foretold would come from the direction of the sunrise.” Montezuma then gave Cortés items of gold as a token of welcome.

Montezuma, ninth ruler of the Aztecs, had interpreted several natural events involving earthquakes, a comet, and a temple fire as omens of the coming end of the Fourth Age of the Aztecs and the beginning the Fifth Age. Also a short time before the arrival of Cortés an unusual light had appeared in the east. When Cortés and his men arrived, Montezuma felt certain they were sent by the feathered deity Quetzalcoatl to begin the Fifth Age.

Coincidentally the Aztec’s religion also had several similarities with the practices of the Franciscan priests with Cortés. The Aztecs revered a cross, which was the emblem of their rain god, they practiced a form of baptism by water, and in their origin story believed a story of virgin birth, and the Aztec priests practiced flagellation and self-mortification similar to that of the Franciscans. These congruencies all reinforced their conviction that they should obey the Spaniards. Combining all these factors with the sense of racial and spiritual superiority held by the Spanish, we can understand why the conquest of Mexico succeeded so quickly. The conquest of Mexico by Cortés proved to be extremely profitable but the conquerers proved to be harsh masters.

Cortés admonished Montezuma for the Aztec’s continued worship of idols and Montezuma was driven to a fury by the insult to his gods. Cortés did not persist immediately, but gradually the amicable relations began to crumble. Montezuma began to place restrictions on the Spaniards’ proposed religious changes. When some Aztecs attacked and defeated a contingent of Spaniards, Cortés and his captains arrested Montezuma. At the confrontation Cortés said, “Lord Montezuma, I am greatly astonished that you, a valiant prince, should have ordered your captains to take up arms against my Spaniards stationed near Tuxpan.” After further protests of indignation Cortés announced, “Everything will be forgiven provided you will now come quietly with us to our quarters with no protest. But if you cry out, or raise any commotion, you will be immediately killed by my captains, whom I have brought for this sole purpose.”

Montezuma was dumbfounded, replying that he had never ordered his people to take up arms, and asked that his own captains be brought in to learn the truth and determine if they should be punished. He further added that no one could give him orders and he did not wish to leave his palace against his will. Bernal Díaz wrote that “Cortés answered him with excellent arguments, which Montezuma countered with even better.” But in the end Montezuma had no choice but to submit to the Spaniards.

During his captivity Montezuma continued to be cared for by his servants, and emissaries from other tribes came to pay him tribute. Soon the Aztec captains confessed their guilt but said that Montezuma had given the order to attack. The guilty captains were burned to death before the royal palace and Montezuma was bound in chains during the execution. After some time a large band of Aztecs, led by a potential successor of Montezuma, began to attack the city. When Montezuma was brought to the parapets to persuade the attackers to stop fighting, a mass of stones and darts came flying through the air and killed Montezuma. This only complicated things for the Spaniards who were low on ammunition and now had no allies to help defend against the attackers. They beat a hasty retreat from the city in the dark of night carrying as much gold as their army and horses could manage. (Note: Aztec versions of this story say the Spaniards killed Montezuma as they fled the city.) In a few months Cortés rebuilt his army and recaptured Mexico, continuing the confiscation of its wealth. Incidentally, one of the captains with Cortés was a young man named Francisco Pizarro who later made a similar conquest of Peru.

The Spanish conquerers committed massacres, torture, and forced conversions in their stated goal of stopping idol worship and human sacrifice among the Aztecs. One must remember, however, that the rationale for going to Mexico in the beginning was gold.

The Spaniards’ glut of gold taken in Mexico set high expectations for all future explorations, not only for the Spanish, but other Europeans as well. The Spanish felt there must be other places equally rich in gold and silver, and heard many rumors of the seven golden cities of Cibola to the north. A medieval legend held that seven Portuguese bishops sailed across the ocean and founded seven cities on the mythical island of Antilla. The seven cities notion reappears centuries later in the Cibola myth. Much exploration was motivated by myths and legends, and a blog here on the power of mythology is in the works.

The idea of seven golden cities of Cibola was given further credibility by Cabeza de Vaca. He arrived in Mexico after an eight-year overland odyssey from Florida to Mexico, survived by only four men. After hearing Cabeza de Vaca’s report, Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza wanted to launch an expedition to the north to investigate these intriguing stories of seven faraway cities of gold. This task eventually fell to Coronado. But a multilingual African slave, Esteban, who had accompanied Cabeza de Vaca, was sent ahead on a reconnaissance in 1539, a year ahead of Coronado. His tale rivals that of Coronado. (to be continued)

References

Díaz, Bernal. The conquest of New Spain. New York: Penguin Books. 1963. Original book published as The true history of the conquest of New Spain. 1568.

Shoumatoff, Alex. Legends of the American Desert. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1997.

During the fifty years after discovery of the New World, Spain’s empire grew to an area larger than the Romans had acquired in 500 years. First the Spanish established colonies on major islands in the Caribbean, i.e., Hispaniola, Cuba, Jamaica. They then explored the gulf coast and the coast of Central America searching for a through passage...to no avail. Balboa crossed the isthmus, sighted, and claimed the Pacific Ocean. Ponce de Leon explored and died in Florida, and the east coast of South America was explored as far south as the Rio de la Plata, now Argentina. Trade of gold ornaments from Indians along the coast of Central America suggested great riches in the interior of these lands, and the inland exploration movement began. The smell of gold induced the viceroy of Cuba to select a promising young man who had helped conquer Cuba as the one who should push into the unknown lands of Mexico, so in 1518 Hernán Cortés undertook the conquest.

This effort was so shockingly easy for 600 soldiers, fifteen horsemen, and fifteen cannon that it is considered nothing short of miraculous. If you recall the story of Kipling’s The Man Who Would be King, you will have some idea of the strategy Cortés followed. He started with only a minimal force of trained, well-armed soldiers and pressed his defeated foes to join the fight against the next enemy. The army grew larger as they conquered successive cities and eventually the cities simply received the Spaniards with no resistance.

This rapid success came partly by force in the beginning, but by the time Cortés and his army reached Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Aztec empire and the largest city in the Americas, cultural factors gave a decided edge to the Spanish. The Europeans brought a combination of things unknown to the Aztecs: horses were totally new and thought to be godly; the Spaniard’s gleaming armor and their noisy, harquebuses were terrifying. These sights alone were enough to convince the Aztecs that these strangers were children of the Sun God. These unusual items however were only a part of the Spanish advantage over the Aztecs. It helped that the Aztec religious culture was already anticipating a major change in the near future.

Bernal Díaz, who was with Cortés, wrote, “As a result of our victories, which God granted us, our fame spread through the surrounding country and reached the ears of the great Montezuma. When the news came that so few of us had conquered such a huge force, terror spread through the whole land.” Montezuma soon sent emissaries to negotiate an annual tribute of gold. The emissaries told Cortés that Montezuma merely wanted to save them the hardships of crossing a “rough and sterile” land to reach the capital city. Cortés ignored their pleas and forged ahead to the riches.

Cortés entered the capital city, which Bernal Díaz calls Mexico, accompanied by three powerful caciques (chieftains) through streets crowded with people from far away who came to see the unknown spectacle of horses and strange light-skinned men. Montezuma sent men to greet Cortés and “as a sign of peace they touched the ground with their hands and kissed it.”

When Cortés met Montezuma he proceeded to give a speech about “how we are all brothers, the children of one mother and father called Adam and Eve; and how a brother, our great Emperor, grieved for the perdition of so many souls and sent us to tell him this that they might give up the worship of idols and taking human sacrifices.”

Surprisingly, Montezuma’s reply was that he was already familiar with much that Cortés was telling him. He said, “Regarding the creation of the world, we have held the same belief for many ages, and are certain you are those who our ancestors foretold would come from the direction of the sunrise.” Montezuma then gave Cortés items of gold as a token of welcome.

Montezuma, ninth ruler of the Aztecs, had interpreted several natural events involving earthquakes, a comet, and a temple fire as omens of the coming end of the Fourth Age of the Aztecs and the beginning the Fifth Age. Also a short time before the arrival of Cortés an unusual light had appeared in the east. When Cortés and his men arrived, Montezuma felt certain they were sent by the feathered deity Quetzalcoatl to begin the Fifth Age.

Coincidentally the Aztec’s religion also had several similarities with the practices of the Franciscan priests with Cortés. The Aztecs revered a cross, which was the emblem of their rain god, they practiced a form of baptism by water, and in their origin story believed a story of virgin birth, and the Aztec priests practiced flagellation and self-mortification similar to that of the Franciscans. These congruencies all reinforced their conviction that they should obey the Spaniards. Combining all these factors with the sense of racial and spiritual superiority held by the Spanish, we can understand why the conquest of Mexico succeeded so quickly. The conquest of Mexico by Cortés proved to be extremely profitable but the conquerers proved to be harsh masters.

Cortés admonished Montezuma for the Aztec’s continued worship of idols and Montezuma was driven to a fury by the insult to his gods. Cortés did not persist immediately, but gradually the amicable relations began to crumble. Montezuma began to place restrictions on the Spaniards’ proposed religious changes. When some Aztecs attacked and defeated a contingent of Spaniards, Cortés and his captains arrested Montezuma. At the confrontation Cortés said, “Lord Montezuma, I am greatly astonished that you, a valiant prince, should have ordered your captains to take up arms against my Spaniards stationed near Tuxpan.” After further protests of indignation Cortés announced, “Everything will be forgiven provided you will now come quietly with us to our quarters with no protest. But if you cry out, or raise any commotion, you will be immediately killed by my captains, whom I have brought for this sole purpose.”

Montezuma was dumbfounded, replying that he had never ordered his people to take up arms, and asked that his own captains be brought in to learn the truth and determine if they should be punished. He further added that no one could give him orders and he did not wish to leave his palace against his will. Bernal Díaz wrote that “Cortés answered him with excellent arguments, which Montezuma countered with even better.” But in the end Montezuma had no choice but to submit to the Spaniards.

During his captivity Montezuma continued to be cared for by his servants, and emissaries from other tribes came to pay him tribute. Soon the Aztec captains confessed their guilt but said that Montezuma had given the order to attack. The guilty captains were burned to death before the royal palace and Montezuma was bound in chains during the execution. After some time a large band of Aztecs, led by a potential successor of Montezuma, began to attack the city. When Montezuma was brought to the parapets to persuade the attackers to stop fighting, a mass of stones and darts came flying through the air and killed Montezuma. This only complicated things for the Spaniards who were low on ammunition and now had no allies to help defend against the attackers. They beat a hasty retreat from the city in the dark of night carrying as much gold as their army and horses could manage. (Note: Aztec versions of this story say the Spaniards killed Montezuma as they fled the city.) In a few months Cortés rebuilt his army and recaptured Mexico, continuing the confiscation of its wealth. Incidentally, one of the captains with Cortés was a young man named Francisco Pizarro who later made a similar conquest of Peru.

The Spanish conquerers committed massacres, torture, and forced conversions in their stated goal of stopping idol worship and human sacrifice among the Aztecs. One must remember, however, that the rationale for going to Mexico in the beginning was gold.

The Spaniards’ glut of gold taken in Mexico set high expectations for all future explorations, not only for the Spanish, but other Europeans as well. The Spanish felt there must be other places equally rich in gold and silver, and heard many rumors of the seven golden cities of Cibola to the north. A medieval legend held that seven Portuguese bishops sailed across the ocean and founded seven cities on the mythical island of Antilla. The seven cities notion reappears centuries later in the Cibola myth. Much exploration was motivated by myths and legends, and a blog here on the power of mythology is in the works.

The idea of seven golden cities of Cibola was given further credibility by Cabeza de Vaca. He arrived in Mexico after an eight-year overland odyssey from Florida to Mexico, survived by only four men. After hearing Cabeza de Vaca’s report, Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza wanted to launch an expedition to the north to investigate these intriguing stories of seven faraway cities of gold. This task eventually fell to Coronado. But a multilingual African slave, Esteban, who had accompanied Cabeza de Vaca, was sent ahead on a reconnaissance in 1539, a year ahead of Coronado. His tale rivals that of Coronado. (to be continued)

References

Díaz, Bernal. The conquest of New Spain. New York: Penguin Books. 1963. Original book published as The true history of the conquest of New Spain. 1568.

Shoumatoff, Alex. Legends of the American Desert. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1997.