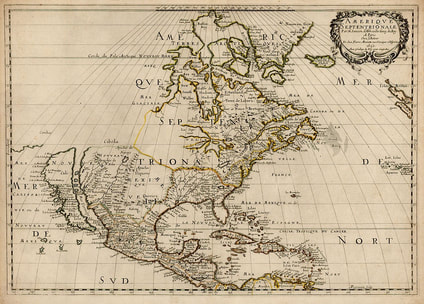

North America drawn in 1650 by Nicholas Sanson (1600-1667). California is shown as an island despite Ulloa’s discovery 111 years earlier. Wikimedia.

North America drawn in 1650 by Nicholas Sanson (1600-1667). California is shown as an island despite Ulloa’s discovery 111 years earlier. Wikimedia. Roger M. McCoy

Wealth, power, and fame were the usual factors driving men to explore unknown lands. Some explorers, however, did not fit this mold. Exceptions include the scientists such as Lewis and Clark, and the company men such as John Rae who went solely to learn everything about a new area. Another exception is the priests who explored new lands with the intention of bringing Christianity to the indigenous people. Although many priests ultimately came, a few stand out for their important discoveries. Two of these are Father Jacques Marquette, who explored the upper Mississippi, and Father Eusebio Kino, who explored and mapped in the southwest deserts.

The Frenchman Jacques Marquette became a Jesuit in 1654 at the young age of seventeen, and stayed in France for several years before being assigned to mission work in the New World. There his task was to create missions and bring Christianity to the indigenous people in the immense area known as New France, which grandly included the St Lawrence River drainage area, the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi valley to the Gulf of Mexico. While among the tribes near La Pointe (Wisconsin) he heard of a great river trade route southward to the oceans. Marquette requested and received permission to join with the French-Canadian Louis Jolliet who was forming an expedition in the Great Lakes region.

Beginning in May, 1673, the expedition traveled on the lakes to the Green Bay of Lake Michigan. Once there they continued up the Fox River toward its headwaters in what is now Wisconsin. Along the way the local natives told them of a short portage (under two miles) to the Wisconsin River, a tributary of the Mississippi. The men of the expedition carried their canoes between rivers and continued to the Mississippi. This portage ultimately became an important route between the east coast and the interior when later a canal with locks was built to handle the traffic.

The expedition traveled down the Mississippi making many contacts with local natives along the way. When they reached the mouth of the Arkansas River (in southern Arkansas) they encountered tribes with European-made trinkets and realized they were approaching Spanish territory. They were only 435 miles from the Gulf, but wanting to avoid a confrontation the expedition turned around and headed back up the Mississippi. They re-entered the Great Lakes at the present site of Chicago after a four month expedition.

Father Marquette returned to the Illinois Territory the next year and died of an illness at St Ignace mission (Michigan) at the age of thirty-seven. Everything learned, from the portage in Wisconsin to the existence of a vast river to the Gulf of Mexico, was all new to the European maps and added to the growing awareness of the immensity of this new continent.

The most remembered priest-explorer in the southwest United States is certainly Father Eusebio Kino (1645-1711), a Jesuit priest of the late seventeenth century. Existing missions or ruins of Kino missions extend across the state of Sonora in Mexico and in southern Arizona. Father Kino’s name is connected to these missions because he arrived in New Spain in 1677 with the assigned task of increasing the presence of Christianity in the region. In fulfilling that commission Kino not only established about two dozen missions but also made important contributions to the map of northern Mexico and southern Arizona.

Born in the northern Italian village of Segno in 1645, Eusebio Kino became a Jesuit at the age of twenty. His preparation for missionary work in the New World included the study of agriculture, animal husbandry, building methods, surveying, cartography, and astronomy; all valuable tools for establishing missions and exploring and mapping new lands. He acquired the skills necessary to show the native people of New Spain how to grow food crops, and raise cattle, goats, and sheep. He came to New Spain with a variety of seeds and starter herds of livestock, which greatly expanded over time. For example, during the course of Kino’s thirty-four year presence in New Spain, his original herd of twenty cattle grew to 70,000.

A priest did not ride in alone unannounced and start building a mission himself. He usually came with a military escort or with priests already known in the area and negotiated with the Indians to convince them to accept the idea of a European coming into their midst. Once established he depended on building a reputation for being of some benefit to the Indians. Then, based on his reputation, he could more easily persuade other groups and tribes to accept him and another new mission would begin. It depended entirely on building a reputation that would precede him as he went to other locations.

Part of the success of a mission depended on providing food, tools, and other supplies to the Indians so they could see how their lives might be improved by learning new methods of agriculture and owning livestock. Those who accepted these innovations could provide a more secure, year-round food supply. The Indians who accepted the mission in their village saw it as a tolerable threat to their way of life, but had little idea how much change they would ultimately have to make. The missionaries saw their work as the only way to bring salvation to the Indians. Hence the mission had different purposes depending on the objectives of the people involved.

Father Kino was not the first missionary into the Pimería Alta region that encompassed today’s states of Sonora and southern Arizona. He was actually building on fifty years work by earlier missionaries. On his arrival in the region he was accompanied by well-known missionaries who introduced him to the Indians. Usually the people of the village knew of the benefits of a missionary in their midst from seeing how well other villages fared by having a mission. Once Kino’s reputation was established, expansion to other villages could be managed without the aid of additional missionaries. During his thirty-four years in New Spain Kino established twenty-four missions in Sonora and Arizona.

Soon after arriving in New Spain 1687, Father Kino traveled to the Baja California peninsula. His map of the area made during that expedition showed that Baja California was a definitely a peninsula and not an island. Although an earlier Spanish expedition by Ulloa in 1539 sailed the Sea of Cortez far enough to map Baja California as a peninsula, by the early 1600’s maps had reverted to showing Baja California as an island. Actually some maps showed all of California as an island. Since Father Kino’s time California has been mapped as part of the mainland. During numerous other expeditions Father Kino mapped over 50,000 square miles of New Spain.

The continuously active San Xavier del Bac mission, standing in a Tohono O’Odham village south of Tucson, Arizona, is a prime example of Spanish Colonial baroque architecture. It serves as a parish church and has a regular schedule of services, led by Franciscan priests. The present building, built in 1785, is within a mile of the original mission site established by Kino in 1692. Most of the other Kino missions have deteriorated to ruins. His earlier studies in architecture and building gave Kino the knowledge to design and oversee the natives’ adobe construction and decoration of these churches.

Many monuments, statues, streets, and geographic features in both Mexico and the United States attest to Father Kino’s importance in the history of the region in the seventeenth century. The towns at eleven Kino mission sites in Mexico, and one in Tumacácori National Historic Park in Arizona, observe Kino festivals with music, dances by local groups, and regional food. Father Kino’s burial site in the city of Magdalena de Kino in Sonora has become a national monument in Mexico.

Sources

Bolton, Herbert Eugene, Rim of Christendom: a biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino, Pacific coast pioneer, Tucson, Ariz.: University of Arizona Press, 1984.

Derleth, August. Father Marquette and the great rivers. New York: Vision Books. 1955.

Polzer, Charles W. Kino: His missions, his monuments. publ. by C.W. Polzer, 1998.

Polzer, Charles W. Kino guide II: a life of Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J., Arizona's first pioneer and a guide to his missions and monuments, Tucson, Ariz.: Southwestern Mission Research Center, 1982.

Shea, John G. Discovery and exploration of the Mississippi Valley. (electronic resource). New York: Redfield. 1852.

Wealth, power, and fame were the usual factors driving men to explore unknown lands. Some explorers, however, did not fit this mold. Exceptions include the scientists such as Lewis and Clark, and the company men such as John Rae who went solely to learn everything about a new area. Another exception is the priests who explored new lands with the intention of bringing Christianity to the indigenous people. Although many priests ultimately came, a few stand out for their important discoveries. Two of these are Father Jacques Marquette, who explored the upper Mississippi, and Father Eusebio Kino, who explored and mapped in the southwest deserts.

The Frenchman Jacques Marquette became a Jesuit in 1654 at the young age of seventeen, and stayed in France for several years before being assigned to mission work in the New World. There his task was to create missions and bring Christianity to the indigenous people in the immense area known as New France, which grandly included the St Lawrence River drainage area, the Great Lakes, and the Mississippi valley to the Gulf of Mexico. While among the tribes near La Pointe (Wisconsin) he heard of a great river trade route southward to the oceans. Marquette requested and received permission to join with the French-Canadian Louis Jolliet who was forming an expedition in the Great Lakes region.

Beginning in May, 1673, the expedition traveled on the lakes to the Green Bay of Lake Michigan. Once there they continued up the Fox River toward its headwaters in what is now Wisconsin. Along the way the local natives told them of a short portage (under two miles) to the Wisconsin River, a tributary of the Mississippi. The men of the expedition carried their canoes between rivers and continued to the Mississippi. This portage ultimately became an important route between the east coast and the interior when later a canal with locks was built to handle the traffic.

The expedition traveled down the Mississippi making many contacts with local natives along the way. When they reached the mouth of the Arkansas River (in southern Arkansas) they encountered tribes with European-made trinkets and realized they were approaching Spanish territory. They were only 435 miles from the Gulf, but wanting to avoid a confrontation the expedition turned around and headed back up the Mississippi. They re-entered the Great Lakes at the present site of Chicago after a four month expedition.

Father Marquette returned to the Illinois Territory the next year and died of an illness at St Ignace mission (Michigan) at the age of thirty-seven. Everything learned, from the portage in Wisconsin to the existence of a vast river to the Gulf of Mexico, was all new to the European maps and added to the growing awareness of the immensity of this new continent.

The most remembered priest-explorer in the southwest United States is certainly Father Eusebio Kino (1645-1711), a Jesuit priest of the late seventeenth century. Existing missions or ruins of Kino missions extend across the state of Sonora in Mexico and in southern Arizona. Father Kino’s name is connected to these missions because he arrived in New Spain in 1677 with the assigned task of increasing the presence of Christianity in the region. In fulfilling that commission Kino not only established about two dozen missions but also made important contributions to the map of northern Mexico and southern Arizona.

Born in the northern Italian village of Segno in 1645, Eusebio Kino became a Jesuit at the age of twenty. His preparation for missionary work in the New World included the study of agriculture, animal husbandry, building methods, surveying, cartography, and astronomy; all valuable tools for establishing missions and exploring and mapping new lands. He acquired the skills necessary to show the native people of New Spain how to grow food crops, and raise cattle, goats, and sheep. He came to New Spain with a variety of seeds and starter herds of livestock, which greatly expanded over time. For example, during the course of Kino’s thirty-four year presence in New Spain, his original herd of twenty cattle grew to 70,000.

A priest did not ride in alone unannounced and start building a mission himself. He usually came with a military escort or with priests already known in the area and negotiated with the Indians to convince them to accept the idea of a European coming into their midst. Once established he depended on building a reputation for being of some benefit to the Indians. Then, based on his reputation, he could more easily persuade other groups and tribes to accept him and another new mission would begin. It depended entirely on building a reputation that would precede him as he went to other locations.

Part of the success of a mission depended on providing food, tools, and other supplies to the Indians so they could see how their lives might be improved by learning new methods of agriculture and owning livestock. Those who accepted these innovations could provide a more secure, year-round food supply. The Indians who accepted the mission in their village saw it as a tolerable threat to their way of life, but had little idea how much change they would ultimately have to make. The missionaries saw their work as the only way to bring salvation to the Indians. Hence the mission had different purposes depending on the objectives of the people involved.

Father Kino was not the first missionary into the Pimería Alta region that encompassed today’s states of Sonora and southern Arizona. He was actually building on fifty years work by earlier missionaries. On his arrival in the region he was accompanied by well-known missionaries who introduced him to the Indians. Usually the people of the village knew of the benefits of a missionary in their midst from seeing how well other villages fared by having a mission. Once Kino’s reputation was established, expansion to other villages could be managed without the aid of additional missionaries. During his thirty-four years in New Spain Kino established twenty-four missions in Sonora and Arizona.

Soon after arriving in New Spain 1687, Father Kino traveled to the Baja California peninsula. His map of the area made during that expedition showed that Baja California was a definitely a peninsula and not an island. Although an earlier Spanish expedition by Ulloa in 1539 sailed the Sea of Cortez far enough to map Baja California as a peninsula, by the early 1600’s maps had reverted to showing Baja California as an island. Actually some maps showed all of California as an island. Since Father Kino’s time California has been mapped as part of the mainland. During numerous other expeditions Father Kino mapped over 50,000 square miles of New Spain.

The continuously active San Xavier del Bac mission, standing in a Tohono O’Odham village south of Tucson, Arizona, is a prime example of Spanish Colonial baroque architecture. It serves as a parish church and has a regular schedule of services, led by Franciscan priests. The present building, built in 1785, is within a mile of the original mission site established by Kino in 1692. Most of the other Kino missions have deteriorated to ruins. His earlier studies in architecture and building gave Kino the knowledge to design and oversee the natives’ adobe construction and decoration of these churches.

Many monuments, statues, streets, and geographic features in both Mexico and the United States attest to Father Kino’s importance in the history of the region in the seventeenth century. The towns at eleven Kino mission sites in Mexico, and one in Tumacácori National Historic Park in Arizona, observe Kino festivals with music, dances by local groups, and regional food. Father Kino’s burial site in the city of Magdalena de Kino in Sonora has become a national monument in Mexico.

Sources

Bolton, Herbert Eugene, Rim of Christendom: a biography of Eusebio Francisco Kino, Pacific coast pioneer, Tucson, Ariz.: University of Arizona Press, 1984.

Derleth, August. Father Marquette and the great rivers. New York: Vision Books. 1955.

Polzer, Charles W. Kino: His missions, his monuments. publ. by C.W. Polzer, 1998.

Polzer, Charles W. Kino guide II: a life of Eusebio Francisco Kino, S.J., Arizona's first pioneer and a guide to his missions and monuments, Tucson, Ariz.: Southwestern Mission Research Center, 1982.

Shea, John G. Discovery and exploration of the Mississippi Valley. (electronic resource). New York: Redfield. 1852.