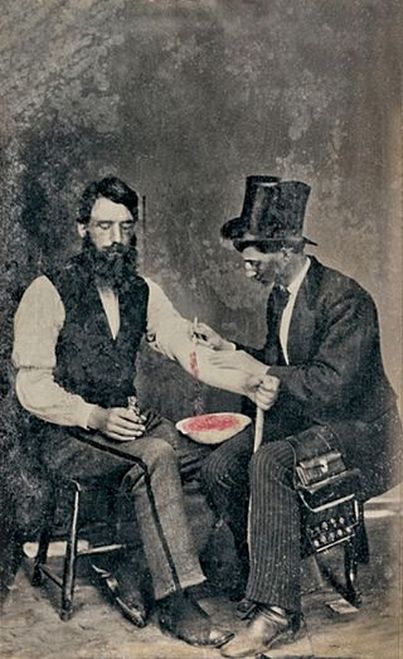

Photograph of bloodletting from 1860. Burns Archive

Photograph of bloodletting from 1860. Burns Archive

From the time of the ancient Greeks through the Renaissance, medicine was dominated by the theory of the four humors or liquids; blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile. Good health depended on their proper balance. All four humors existed in the blood in varying amounts, and if a person had too much of one humor they fell ill. The treatment for most illnesses required removal of certain bodily fluids which contained the humors. For example, if a person had a fever, which included most sicknesses, he must have too much blood. The treatment was to cut the patient and let him bleed. In addition to bleeding, evacuation of fluids in the bowel or stomach were common treatment. These ideas persisted into the Renaissance before changes in medical practices began to appear.

In the Middle Ages people in Europe turned to religion for guidance in all matters of their lives. The view of Christians and Jews during the darkest ages was that illness was usually God’s punishment for sin. (You may have noticed this idea is not yet totally dead.) Care for the sick was considered a noble thing, so Christian groups, often monasteries, set up hospitals. Despite the fact that monks preserved and copied ancient medical books, they made little effort to put the ancient practices to use. Mostly they directed their efforts toward keeping the sick comfortable during their affliction. St. Benedict actually ordered his monks not to study medicine, because he felt that only God could heal the sick. As a result of these practices, the early medical knowledge of the Greeks, Romans, was forgotten in Europe.

Islamic scholars preserved and practiced the ancient medicine, the theory of humors in the blood, translated it into Arabic, and spread it with their empire over North Africa, parts of Spain, and France. They even produced medical encyclopedias that were owned by every practicing physician in the Islamic empire. During the Renaissance medical knowledge made a return to Europe and expanded beyond the works of Galen and other ancients, and a few doctors began to rely more on observations and experiments. Acceptance of this new approach to medicine was slow and required several hundred additional years. This brings us to the time of exploration at the beginning of the sixteenth century.

Explorers had little knowledge of the humors and a physician or surgeon seldom traveled with their expeditions. Their medical practice was often done by a crew member with barbering tools who cut hair, pulled teeth, and performed simple operations such as amputations and setting broken bones. Besides his razors, the designated barber-surgeon also carried saws, pliers, and ointments, and herbal medicines, along with a syringe used to clean wounds with sea water or rum. Internal surgery was a certain way to death by infection and was avoided except by a few daring surgeons.

Sailors in the sixteenth century did extremely hazardous work and injuries were common. Wounds and broken bones headed the list of injuries and amputation was the universal treatment. The greatest danger, however, on long voyages was scurvy. The cause of scurvy was unknown, but sailors were aware that certain foods could cure it. Unfortunately fresh fruits, vegetables, or meat on board were soon consumed, and the rest of the voyage was dangerously deficient of foods containing vitamin C. After about six weeks of salted meat and hardtack the first symptoms of scurvy began to appear—swelling of the gums and loosening of teeth, then blotches on the skin followed by a deep lethargy leading to death. Consumption of vitamin C could quickly correct these symptoms—except for the death part.

It was not until 1747 that a systematic experiment was conducted by James Lind, a British naval physician, to study the effects of citrus fruits on the disease. Lind, like others of his time, believed that scurvy was caused by putrefaction in the body, and that the acidity of citrus fruit corrected it. Even though Lind demonstrated the benefits of citrus, it was not until 1795 that lemon juice was required to be carried on ships of the English navy. In the mid-nineteenth century lemon juice was replaced by lime juice because of lower costs. Also they discovered that limes are only half as effective as lemons for preventing scurvy.

Many theories had been developed about the causes of illness and infections, and the term “fever” covered most illnesses. Ridding the body of unwanted elements involved strong laxatives, bleeding, and sometimes emetics (think vomiting). Nobody knew how much blood was enough, so there was an inclination to take some amount—up to a pint—and if the patient did not improve, draw more. They realized that too much blood loss could lead to death, but they often pushed the limits in an effort to remove enough of the bad element. Another cause of disease was believed to be the foul smelling emanation (miasma) from swamps, rotting organic matter, or raw sewage. Some fevers, particularly malaria, were believed to be related to these miasmas.

In 1803 the Corps of Discovery, headed by Lewis and Clark, was making preparations for the journey up the MIssouri River and to the west coast of the continent. Part of their preparation included planning for medical needs, both for the men on the journey and for Indians they encountered along the way. For this purpose they sought the advice of one of the most respected physicians of the day, Dr. Benjamin Rush. Dr. Rush was a strong advocate of bleeding. To him there was only one kind of fever and one disease, and it was based on imbalance in the vascular system, especially in the brain. Accordingly his advice to Lewis and Clark involved laxatives, emetics, and tools for bleeding. Men on the Lewis and Clark expedition had diets low in fruits, vegetables, and other sources of fiber, so they frequently had need for Dr. Rush’s powerful laxative remedy, which they called “thunderclappers.” Rush also believed in a concept called “heroic medicine” with bleeding to the point of fainting and purging at dosages sufficient for a horse. I think the heroic part was mere survival of the treatment. Surprisingly, patients often said they felt better after a blood draw, even an amount that caused them to faint. In fact Benjamin Rush often advocated bleeding until faintness, then bleeding again the next day. If this was repeated several times, the patient would become severely anemic and require weeks to recover a normal red blood cell count.

An adult male in good health has about 10 pints (4.7 liters) of blood, females slightly less. Removal of 3 pints causes a big drop in blood pressure and fainting. Removal of 4 pints suddenly can be fatal if not replaced quickly. One of the best known examples is the final illness of George Washington on December 14, 1799. He was deathly ill with a severe throat infection and pneumonia. At 7:30 A.M. Washington was bled 14 ounces, almost a pint. At 9:30 he was bled a pint and a half, and again at 11:00 A.M. A short time later Washington felt enough better to get out of bed and walk around the room. At 3 P.M. another 2 pints were removed and at 4:00 P.M. he was given both a laxative and an emetic. Washington again improved briefly but was acutely short of breath to the point that the attending physicians considered a tracheotomy. At 10:20 P.M. Washington died after a total loss of 5 pints of blood in twelve hours. Pneumonia was given as the cause of death, but the treatment must have hastened his passing.

References

McCoy, R.M. On the edge: Mapping North America’s Coasts. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012

Paton, B.C. Lewis and Clark: Doctors in the wilderness. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing. 2001

Yount, Lisa, The history of medicine, San Diego: Lucent Books, 2002