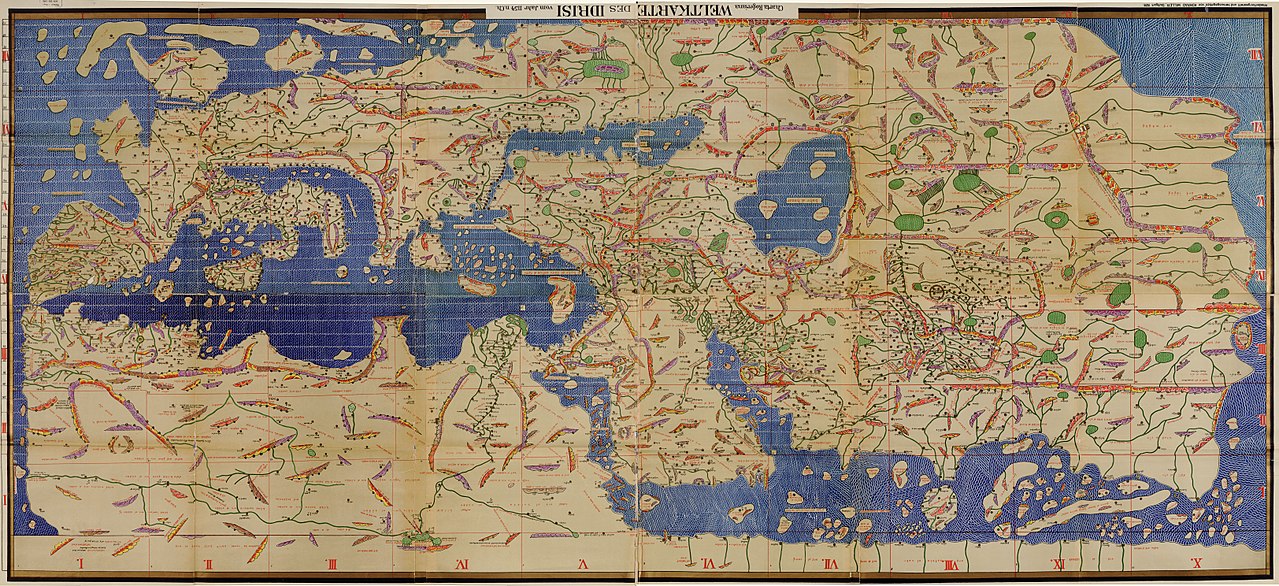

Muhammed al-Idrisi’s interesting world map made in 1154 A.D. This view is inverted as the original map had north at the bottom. Wikimedia Commons

Muhammed al-Idrisi’s interesting world map made in 1154 A.D. This view is inverted as the original map had north at the bottom. Wikimedia Commons Roger M. McCoy

We sometimes think that Columbus was the first to consider sailing westward to Asia in 1492, but we find that others tried many years before Columbus.

In 1154 the Arab geographer and cartographer, Muhammed al-Idrisi, compiled information from travelers and explorers and produced the most accurate map of the known world at the time. Al-Idrisi’s impressive map remained the standard of accuracy until 1507 when Johannes Ruysch and Martin Waldseemüller each produced maps that included the New World. The illustration above of the al-Idrisi map shows that someone who understood the spherical shape of the Earth could hypothesize sailing westward from Europe to reach Asia. In the Middle Ages the estimated circumference of the Earth was significantly less than the actual distance, so a person might also guess that the voyage would not be too long. A few men tried and never returned and several factors probably stalled others from such a venture. One possible reason might be that ships of that time were designed for travel in the Mediterranean and were not sufficiently seaworthy for crossing a large, unknown ocean. Whatever the reason, sailing west to Asia was not yet feasible in the Middle Ages.

By the late thirteenth century Europeans showed an increased interest in exploring the world. Failed attempts seldom make it into the history books, but one little known effort occurred in 1291 by two brothers, Ugolino and Guido Vivaldi. They set out in two small ships sailing westerly in hopes of finding India. Both ships were lost and never returned. There were other similar probes with no luck. The lure of spices and silk fabric urged others to keep trying but with little success.

Around the year 1300 Marco Polo returned from twenty-four years of travel in China and other Asian countries. He immediately wrote a widely- read book of his experience titled Livres des mervbeilles du monde, usually called in English, The travels of Marco Polo. This book had wide appeal to Europeans most of whom had focussed inwardly for centuries with little knowledge of the rest of the world. Although a few others had visited China, Polo was the first to write about it in great detail. His description of silk cloth and exotic spices did much to stimulate interest in travel and exploration outside the bounds of Europe and the Mediterranean Sea. Even Columbus claimed to be inspired by Polo’s book some 190 years after its publication.

A lesser motivation for travel to other parts of the world was the persistent rumor of a Christian king called Prester John, who reigned in an unknown area believed at various times to be in Mongolia, India, and Ethiopia. Adventurers of the twelfth century hoped to find this imaginary ruler.

In the early fifteenth century a Portuguese nobleman, Prince Henry the Navigator, sent ships to explore nearby parts of the Atlantic Ocean and down the west coast of Africa. The African coast was totally unexplored and considered by some sailors to be potentially dangerous with sea monsters, and possibly on the edge of the world. In 1434 one of Prince Henry’s ship captains became the first European to sail southward past Cape Bojador at the western bulge of Africa. Until then no European had sailed beyond that point. By 1462 the Portuguese had explored around the west bulge of Africa and reached the coast that today comprises countries of Sierra Leone and Liberia.

Henry’s expeditions also sailed westward to discover the Madeira Islands and the Azores. Henry documented these discoveries by engaging cartographers to map the newly found places. In another major benefit to sailors, Prince Henry’s navigators discovered the important advantage of using the easterly Trade Winds for sailing west, then sailing north into the Westerlies for sailing eastward back to Europe, thus closing a circuit that navigators continued using until the advent of steam-powered ships. Finally in 1497 Vasco de Gama, sailing for the Portuguese, made it all the way to India around Cape of Good Hope giving Portugal the first all-sea route to the Orient from Europe.

This was all fine for Portugal, but other maritime countries such as Spain were blocked by Portugal from sailing along this route. This led to disputes between Portugal and Spain. The Portuguese King, Alfonso V, entreated Pope Nicholas V to establish specific spheres of influence for their ventures as well as those of the Spanish. The pope obliged in exchange for Portuguese help against the Turks. In 1452 the pope issued a papal bull, titled Dum Diversas, (Until Different). In this bull the pope agreed to sanction Portuguese claims in Africa. The excerpt below shows not only the pope’s support of Portuguese claims, but goes further by sanctioning capture and subjugation of pagans and unbelievers. This is an important document that led to invasions, cruelty, and enslavement of indigenous people by many European explorers. These words of Pope Nicholas V initiated centuries of invasions, massacres, and rapine in the name of Christianity.

We grant you (meaning the kings of Spain and Portugal) by these present documents, with our Apostolic Authority, full and free permission to invade, search out, capture, and subjugate the Saracens and pagans and any other unbelievers and enemies of Christ wherever they may be, as well as their kingdoms, duchies, counties, principalities, and other property ... and to reduce their persons into perpetual servitude.

Two years later the same pope expanded on the previous bull with another called Romanus Pontifex (Roman Pontiff). This bull confirmed that the king of Portugal had dominion over all lands south of Cape Bojador in Africa. In addition to encouraging the seizure of the lands of Saracen Turks and other non-Christians, it also repeated the earlier bull's permission for the enslavement of such peoples. The bull's primary purpose was to prevent other nations from infringing on Portugal's rights of trade and colonization in these regions. The bull stated that the Portuguese may provide the indigenous people “the reward of eternal felicity, and obtain pardon for their souls…and to incite them to aid the Christians against the Saracens …” The Romanus Pontifex became the basis for Christian explorers to “invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue” non-Christian people; to steal “all movable and immovable goods,” and to “reduce their persons to perpetual slavery” in the name of Christianity.

Thus we see the unknown world divided for exploitation between the Portuguese and the Spanish and the stage is set for both conversion and enslavement of non-Christian indigenous people. Other countries were not included in this bull and the countries of northwest Europe chose to ignore the edict. England, France, and the Netherlands claimed land in northern portions of the New World with little or no repercussion from Spain and Portugal.

This brings us to the year 1492 and Columbus’s voyage west to reach the Orient by a route that avoided the Portuguese control of the African route. This venture never reached Asia, but instead rediscovered (see Vikings, May 2017) the New World that attracted many explorers and settlers from western Europe.

Sources

Fried, Johannes. (translated by Peter Lewis) The Middle Ages, Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. 2015.

Rotandaro, Vinnie. Disastrous doctrine had papal roots. Kansas City, MO: National Catholic Reporter. 2015.