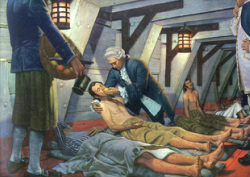

James Lind treating scurvy (Tauss Marine)

James Lind treating scurvy (Tauss Marine) Roger M. McCoy

It is impossible to read about the early explorers without confronting the main problem they all faced: scurvy. Almost no explorer’s voyage escaped without some presence of this dreaded disease. Sometimes it debilitated almost the entire ship’s crew.

Although people held several beliefs about its causes, and a few happened onto effective preventive measures, there was no attempt to understand the disease until the mid-eighteenth century…the beginnings of modern science. The cause of scurvy was variously believed to be bad air, e.g. foul odors from the bilges of ships, or spoiled food, which was abundant but eaten despite spoilage. Attempts at a remedy came when early voyagers to the Orient saw sailors eating certain foods believed to prevent scurvy. In many places sailors found antiscorbutic (scurvy preventing) plants such as sorrel or scurvy grass.

Sorrel (sometimes called spinach dock) is found in many temperate and arctic areas near salt marshes along coasts. Scurvy grass (a member of the cabbage family) also has a wide distribution. A problem was that these plants were not always present where the men happened to go ashore. Apparently not all sailors were aware of their value, or if they were, they simply did not bother to use them. Hardtack and dried meat was the standard. Different foods, like different ideas, are usually adopted very slowly. Therefore, the problem of scurvy persisted among sailors through the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century.

About six weeks into a voyage the first symptoms of scurvy might begin. Before any visible symptoms appear, a sailor would begin to feel easily fatigued and listless. Early indications were tenderness and festering of old, healed wounds. Later the gums would begin to bleed and teeth loosen. Old sailors often had missing teeth as a reminder of their scurvy past. Soon black blotches began to appear on gums and skin. Later the muscles became weak and unable to move...total lethargy sets in. If nothing is done, death is inevitable. Fortunately, all symptoms could disappear within three days if proper diet was restored.

The importance of diet was demonstrated on Jacques Cartier’s voyage to the St. Lawrence River in 1535. Eight of his crew died and fifty others were totally disabled by scurvy until the local natives gave them a tea brewed with foliage and bark of the Eastern Arborvitae twice a day. The recovery was so rapid and complete that Cartier declared a miracle had been performed.

In 1747 a surgeon of the Royal Navy, James Lind, completed a study in which he observed and treated victims of scurvy with various foods, especially limes and lemons. In 1753 (a six year lag) he published his results, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in which he described all aspects of the disease and its remedies, with speculation of possible causes. Lind concluded that scurvy had two probable causes; cold damp conditions and deficiency of fresh vegetables. He wrote that scurvy “may be occasioned by an intense degree of cold, during a severe winter, and nothing so effectually relieves the patient as the return of warm weather. Also when it [scurvy] is produced by a long abstinence from green vegetables, it is often soon removed by a plentiful use of them.” No doubt the return to warm weather was accompanied by a better diet.

Lind’s recommendation was that lemon juice be carried aboard British ships at all times. Forty-two years after this recommendation the Royal Navy finally made such a requirement. More than 150 years before Lind’s study, Admiral Sir Richard Hawkins of the Royal Navy had made the same recommendation. The wheels of change move very slowly.

Finally, in the nineteenth century a few explorers began to notice that Inuits inhabited the Arctic all through the winter with no vegetables in their diet and with no sign of scurvy. John Rae, an employee of the Hudson Bay Company, followed the Inuit customs and carried almost no food provisions when he traveled overland in the winters of the 1850’s. He and his crew subsisted on fresh meat, such as caribou and seal, for months at a time. By eating both muscle meat and organs such as liver they maintained a diet that prevented scurvy.

The disease was particularly difficult to understand because sailors on long voyages could still get scurvy even with regular use of citric juices. Unknown to them at the time was the problem that citric juices became ineffective against scurvy after months of storage. Captain William Parry confronted this problem on his voyage to the Arctic in 1821-1823 by taking mustard and cress seed to grow fresh greens during the long winters locked in ice. He placed the seed beds near heating ducts running through the ship. By spring his plantings had produced more than one hundred pounds of greens.

After many hard lessons on survival in the Arctic, everyone felt confident that the scurvy menace had been solved. Then in 1875 the George Nares expedition left for a scientific survey of the north coast of Ellesmere Island...and a push to reach the North Pole. They thought they were prepared to meet all the difficulties, but in fact they ignored most of the valuable experiences of previous explorers. Among many lapses, they did not bother with rum in the lime juice and the kegs froze solid. Soon men began to complain of fatigue and other early signs of scurvy. Illness became such a problem for the sledge party headed for the Pole that they had to turn back. Before long most men were being carried on sledges rather than helping pull them, and by the time they returned to the ship only three of fifteen men could still walk. Other sledge parties had the same experience. Men manning the base ship during this time fell ill also. Only nine out of fifty-three were able do the necessary work. The expedition was aborted a year early, and the ship returned to England amid a storm of criticism for failing to reach the Pole. The Nares expedition had sufficient knowledge to survive in the Arctic, but ignored everything and carried on in the traditional manner. Such attitudes set back practices for the prevention of scurvy by fifty years.

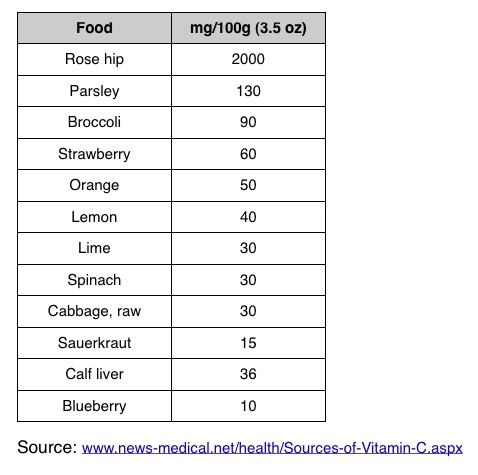

Until the early twentieth century vitamins were unknown, and not until 1928 was vitamin C identified and recognized as the antiscorbutic that made citrus fruit so important to explorers. James Lind guessed that the acidity of lemons prevented scurvy, but could not explain why other acids had no similar effect. After the discovery of vitamin C, researchers sought to determine the vitamin C concentration of all foods and the minimum amount that humans needed to prevent scurvy. A sample of their results shows a wide range of sources for vitamin C as seen in the table below. The minimum needed for prevention of scurvy in humans averages about 60 mg/day. Good diet and diet supplements have made scurvy a rare disease today.

It is impossible to read about the early explorers without confronting the main problem they all faced: scurvy. Almost no explorer’s voyage escaped without some presence of this dreaded disease. Sometimes it debilitated almost the entire ship’s crew.

Although people held several beliefs about its causes, and a few happened onto effective preventive measures, there was no attempt to understand the disease until the mid-eighteenth century…the beginnings of modern science. The cause of scurvy was variously believed to be bad air, e.g. foul odors from the bilges of ships, or spoiled food, which was abundant but eaten despite spoilage. Attempts at a remedy came when early voyagers to the Orient saw sailors eating certain foods believed to prevent scurvy. In many places sailors found antiscorbutic (scurvy preventing) plants such as sorrel or scurvy grass.

Sorrel (sometimes called spinach dock) is found in many temperate and arctic areas near salt marshes along coasts. Scurvy grass (a member of the cabbage family) also has a wide distribution. A problem was that these plants were not always present where the men happened to go ashore. Apparently not all sailors were aware of their value, or if they were, they simply did not bother to use them. Hardtack and dried meat was the standard. Different foods, like different ideas, are usually adopted very slowly. Therefore, the problem of scurvy persisted among sailors through the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century.

About six weeks into a voyage the first symptoms of scurvy might begin. Before any visible symptoms appear, a sailor would begin to feel easily fatigued and listless. Early indications were tenderness and festering of old, healed wounds. Later the gums would begin to bleed and teeth loosen. Old sailors often had missing teeth as a reminder of their scurvy past. Soon black blotches began to appear on gums and skin. Later the muscles became weak and unable to move...total lethargy sets in. If nothing is done, death is inevitable. Fortunately, all symptoms could disappear within three days if proper diet was restored.

The importance of diet was demonstrated on Jacques Cartier’s voyage to the St. Lawrence River in 1535. Eight of his crew died and fifty others were totally disabled by scurvy until the local natives gave them a tea brewed with foliage and bark of the Eastern Arborvitae twice a day. The recovery was so rapid and complete that Cartier declared a miracle had been performed.

In 1747 a surgeon of the Royal Navy, James Lind, completed a study in which he observed and treated victims of scurvy with various foods, especially limes and lemons. In 1753 (a six year lag) he published his results, A Treatise on the Scurvy, in which he described all aspects of the disease and its remedies, with speculation of possible causes. Lind concluded that scurvy had two probable causes; cold damp conditions and deficiency of fresh vegetables. He wrote that scurvy “may be occasioned by an intense degree of cold, during a severe winter, and nothing so effectually relieves the patient as the return of warm weather. Also when it [scurvy] is produced by a long abstinence from green vegetables, it is often soon removed by a plentiful use of them.” No doubt the return to warm weather was accompanied by a better diet.

Lind’s recommendation was that lemon juice be carried aboard British ships at all times. Forty-two years after this recommendation the Royal Navy finally made such a requirement. More than 150 years before Lind’s study, Admiral Sir Richard Hawkins of the Royal Navy had made the same recommendation. The wheels of change move very slowly.

Finally, in the nineteenth century a few explorers began to notice that Inuits inhabited the Arctic all through the winter with no vegetables in their diet and with no sign of scurvy. John Rae, an employee of the Hudson Bay Company, followed the Inuit customs and carried almost no food provisions when he traveled overland in the winters of the 1850’s. He and his crew subsisted on fresh meat, such as caribou and seal, for months at a time. By eating both muscle meat and organs such as liver they maintained a diet that prevented scurvy.

The disease was particularly difficult to understand because sailors on long voyages could still get scurvy even with regular use of citric juices. Unknown to them at the time was the problem that citric juices became ineffective against scurvy after months of storage. Captain William Parry confronted this problem on his voyage to the Arctic in 1821-1823 by taking mustard and cress seed to grow fresh greens during the long winters locked in ice. He placed the seed beds near heating ducts running through the ship. By spring his plantings had produced more than one hundred pounds of greens.

After many hard lessons on survival in the Arctic, everyone felt confident that the scurvy menace had been solved. Then in 1875 the George Nares expedition left for a scientific survey of the north coast of Ellesmere Island...and a push to reach the North Pole. They thought they were prepared to meet all the difficulties, but in fact they ignored most of the valuable experiences of previous explorers. Among many lapses, they did not bother with rum in the lime juice and the kegs froze solid. Soon men began to complain of fatigue and other early signs of scurvy. Illness became such a problem for the sledge party headed for the Pole that they had to turn back. Before long most men were being carried on sledges rather than helping pull them, and by the time they returned to the ship only three of fifteen men could still walk. Other sledge parties had the same experience. Men manning the base ship during this time fell ill also. Only nine out of fifty-three were able do the necessary work. The expedition was aborted a year early, and the ship returned to England amid a storm of criticism for failing to reach the Pole. The Nares expedition had sufficient knowledge to survive in the Arctic, but ignored everything and carried on in the traditional manner. Such attitudes set back practices for the prevention of scurvy by fifty years.

Until the early twentieth century vitamins were unknown, and not until 1928 was vitamin C identified and recognized as the antiscorbutic that made citrus fruit so important to explorers. James Lind guessed that the acidity of lemons prevented scurvy, but could not explain why other acids had no similar effect. After the discovery of vitamin C, researchers sought to determine the vitamin C concentration of all foods and the minimum amount that humans needed to prevent scurvy. A sample of their results shows a wide range of sources for vitamin C as seen in the table below. The minimum needed for prevention of scurvy in humans averages about 60 mg/day. Good diet and diet supplements have made scurvy a rare disease today.

Sources

Carpenter, Kenneth. The History of Scurvy and vitamin C. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987

Lind, James. A Treatise on the Scurvy. London: A. Miller. 1757.

McCoy, Roger M. On the Edge: Mapping North America’s Coasts. New York: Oxford University Press. 2012.

Carpenter, Kenneth. The History of Scurvy and vitamin C. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987

Lind, James. A Treatise on the Scurvy. London: A. Miller. 1757.

McCoy, Roger M. On the Edge: Mapping North America’s Coasts. New York: Oxford University Press. 2012.