Roger M McCoy

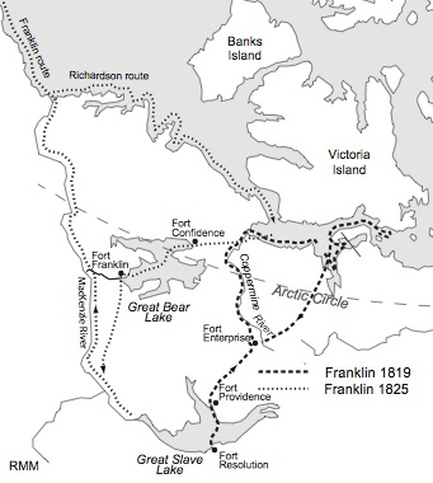

In 1844, Sir John Barrow, Second Secretary of the Admiralty, planned one more effort to find the Northwest Passage before his imminent retirement. Any ambitious naval officer would have been eager to lead such an expedition. After lengthy consideration of their experienced officers, the Admiralty chose Sir John Franklin, leader of two prior expeditions (Explorer’s Tales, 9/2/2015) , to plan and execute this expedition.

The ships Erebus and Terror were refitted with railroad steam engines as an aid in pushing through ice-choked waters when winds were calm or adverse. Franklin claimed, with questionable wisdom, that twenty-horsepower steam engines could be installed along with the necessary coal without destroying the ships’ capacity for stores and provisions. They installed screw-type propellers that could be raised out of the water while the ships were under sail. An enormous amount of planning and ship refitting went into the preparations. In all there were to be 129 officers and men aboard the two ships, with provisions and supplies for three years, including ample supplies of lemon juice, canned vegetables, and canned meat. The inevitable infamous sea biscuit steadfastly remained, baked months in advance by naval bakeries and were often infested with weevil larvae by the time they were loaded on the ship. (French ships reportedly carried flour and baked their bread on board.) It was without doubt the most thoroughly prepared expedition up to that time. An interesting aside is that the Terror took part in the British bombings of Fort McHenry in the Battle of Baltimore in 1814, during which Francis Scott Key wrote a poem about the flag that was still there.

On May 19, 1845 the two ships sailed down the Thames to begin the most elaborately planned and provisioned expedition ever to search for the Northwest Passage. The exploration of the Arctic had captured the interest of the British public but this expedition, perhaps more than any other, carried the aspirations and best wishes of all Britain. The men of the expedition had complete confidence in Franklin because of his past experience and good rapport with his officers. The ships had everything deemed necessary for a successful voyage, and failure seemed impossible.

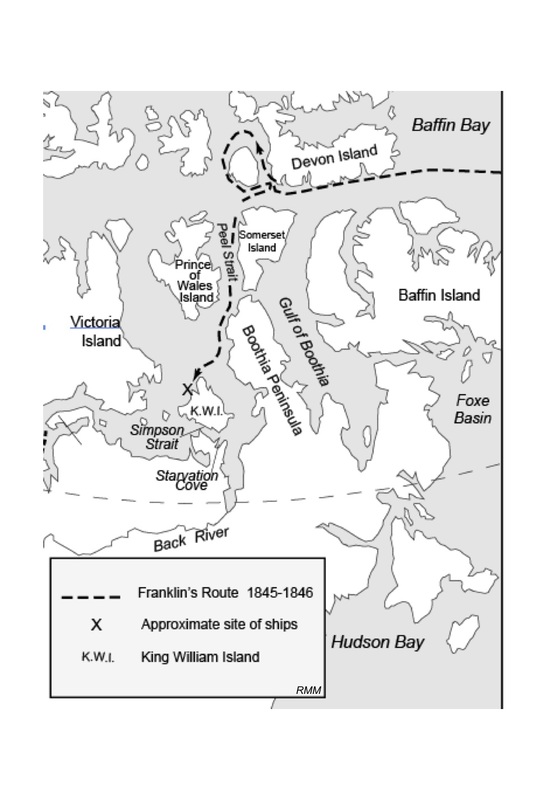

Near the end of July,1845 two British whaling ships reported sighting the Erebus and Terror progressing westward in Baffin Bay in excellent condition, but the ships and men of the Franklin expedition were never seen again.

The Search Begins

Sir John Ross, a naval officer with Arctic experience, expressed his misgivings about the suitability of the Erebus and Terror before Franklin had even departed in 1845. Ross’s previous heroic experience with Arctic survival led him to believe the two ships were too large, the drafts too deep (nineteen feet), the crews were too large (a potential problem if short rations became necessary), the steam engines and coal added too much weight, making them ride low in the water, and the steam engines and coal took space that could better be used for provisions. Ross’s convictions on these issues prompted him to advise Franklin to leave frequent cairns along the way with notes telling his intended direction of travel, and to leave food caches at intervals in case he should lose the ships and have to walk out as Ross had done. Further, he told Franklin that he would be prepared to lead a rescue party if Franklin’s whereabouts were not known by February, 1847. All these well-founded misgivings were ignored by both Franklin and the Admiralty in their conviction that they had made all the best decisions. Optimism ruled everyone’s thinking, and the Admiralty felt they had planned a fail-proof expedition.

In the spring of 1848 the expedition was declared missing and a large search and rescue project began from three directions. Two ships, the Enterprise under James Ross and Investigator under Edward Bird approached from the east into Lancaster Sound. One ship, under the command of Captain Henry Kellett, was sent around Cape Horn to approach through Bering Strait. Richardson and Rae traveled overland down the Mackenzie River and eastward along the coast looking for signs of Franklin. Unsurprisingly they found nothing. The route Franklin was expected to have taken two years earlier was blocked by ice when the searchers arrived, so they assumed Franklin could not have gone that route. Unfortunately, the naval officers were not yet familiar with significant year-to-year variations in the location of ice floes during the summer season. The result was that they initially searched only in ice-free areas—most of which were not part of Franklin’s planned route.

The Admiralty was considering ending the search when pressure from naval officers persuaded them to prolong the search. In the spring of 1850 a veritable armada of ships set out to look for Franklin, and the Admiralty offered a prize of £20,000 for the rescue of Franklin and £10,000 for finding his ships. Two ships approached the Arctic from the west through Bering Strait and thirteen ships made an eastern approach into Lancaster Sound. One ship was financed by Lady Jane Franklin, along with private subscriptions, and two American ships joined the fleet. All they found were three graves on Beechey Island, next to Devon Island, with names of men known to be part of Franklin’s crew. At that site searchers also found a quantity of empty food containers suggesting a layover during the expedition’s first winter. They found rock cairns that strangely contained no message indicating where the ships might have gone. At the end of summer most of the search ships stayed through the winter for another attempt the following summer.

Lady Jane Franklin differed with the Admiralty on the likely place to look for Franklin, pressing them to expand the search south of Lancaster Sound where the expedition originally intended to go. The Admiralty repeatedly sent expeditions to the north and west, even though they were unlikely to find Franklin by repeating the same mistake. It made no difference to her that on January 19, 1854 the British Government officially pronounced the men of the expedition dead. She was determined to find them dead or alive, in part to vindicate her husband as the one who completed the Northwest Passage. Lady Jane spent much of her personal money on three unsuccessful expeditions searching for her husband. She was frustrated that so many ships were sent in what she thought was the wrong direction.

Ultimately her intuition proved to be right. In 1857 Lady Jane arranged for Francis Leopold M’Clintock to sail the Fox, a ship she financed with £2,000 of her own money plus public subscription. M’Clintock knew the techniques for overland travel and survival in the Arctic, and his skills and persistence helped him learn what had happened to the Franklin expedition. In Part 3 we will see the ghastly outcome of M’Clintock’s search.

In 1844, Sir John Barrow, Second Secretary of the Admiralty, planned one more effort to find the Northwest Passage before his imminent retirement. Any ambitious naval officer would have been eager to lead such an expedition. After lengthy consideration of their experienced officers, the Admiralty chose Sir John Franklin, leader of two prior expeditions (Explorer’s Tales, 9/2/2015) , to plan and execute this expedition.

The ships Erebus and Terror were refitted with railroad steam engines as an aid in pushing through ice-choked waters when winds were calm or adverse. Franklin claimed, with questionable wisdom, that twenty-horsepower steam engines could be installed along with the necessary coal without destroying the ships’ capacity for stores and provisions. They installed screw-type propellers that could be raised out of the water while the ships were under sail. An enormous amount of planning and ship refitting went into the preparations. In all there were to be 129 officers and men aboard the two ships, with provisions and supplies for three years, including ample supplies of lemon juice, canned vegetables, and canned meat. The inevitable infamous sea biscuit steadfastly remained, baked months in advance by naval bakeries and were often infested with weevil larvae by the time they were loaded on the ship. (French ships reportedly carried flour and baked their bread on board.) It was without doubt the most thoroughly prepared expedition up to that time. An interesting aside is that the Terror took part in the British bombings of Fort McHenry in the Battle of Baltimore in 1814, during which Francis Scott Key wrote a poem about the flag that was still there.

On May 19, 1845 the two ships sailed down the Thames to begin the most elaborately planned and provisioned expedition ever to search for the Northwest Passage. The exploration of the Arctic had captured the interest of the British public but this expedition, perhaps more than any other, carried the aspirations and best wishes of all Britain. The men of the expedition had complete confidence in Franklin because of his past experience and good rapport with his officers. The ships had everything deemed necessary for a successful voyage, and failure seemed impossible.

Near the end of July,1845 two British whaling ships reported sighting the Erebus and Terror progressing westward in Baffin Bay in excellent condition, but the ships and men of the Franklin expedition were never seen again.

The Search Begins

Sir John Ross, a naval officer with Arctic experience, expressed his misgivings about the suitability of the Erebus and Terror before Franklin had even departed in 1845. Ross’s previous heroic experience with Arctic survival led him to believe the two ships were too large, the drafts too deep (nineteen feet), the crews were too large (a potential problem if short rations became necessary), the steam engines and coal added too much weight, making them ride low in the water, and the steam engines and coal took space that could better be used for provisions. Ross’s convictions on these issues prompted him to advise Franklin to leave frequent cairns along the way with notes telling his intended direction of travel, and to leave food caches at intervals in case he should lose the ships and have to walk out as Ross had done. Further, he told Franklin that he would be prepared to lead a rescue party if Franklin’s whereabouts were not known by February, 1847. All these well-founded misgivings were ignored by both Franklin and the Admiralty in their conviction that they had made all the best decisions. Optimism ruled everyone’s thinking, and the Admiralty felt they had planned a fail-proof expedition.

In the spring of 1848 the expedition was declared missing and a large search and rescue project began from three directions. Two ships, the Enterprise under James Ross and Investigator under Edward Bird approached from the east into Lancaster Sound. One ship, under the command of Captain Henry Kellett, was sent around Cape Horn to approach through Bering Strait. Richardson and Rae traveled overland down the Mackenzie River and eastward along the coast looking for signs of Franklin. Unsurprisingly they found nothing. The route Franklin was expected to have taken two years earlier was blocked by ice when the searchers arrived, so they assumed Franklin could not have gone that route. Unfortunately, the naval officers were not yet familiar with significant year-to-year variations in the location of ice floes during the summer season. The result was that they initially searched only in ice-free areas—most of which were not part of Franklin’s planned route.

The Admiralty was considering ending the search when pressure from naval officers persuaded them to prolong the search. In the spring of 1850 a veritable armada of ships set out to look for Franklin, and the Admiralty offered a prize of £20,000 for the rescue of Franklin and £10,000 for finding his ships. Two ships approached the Arctic from the west through Bering Strait and thirteen ships made an eastern approach into Lancaster Sound. One ship was financed by Lady Jane Franklin, along with private subscriptions, and two American ships joined the fleet. All they found were three graves on Beechey Island, next to Devon Island, with names of men known to be part of Franklin’s crew. At that site searchers also found a quantity of empty food containers suggesting a layover during the expedition’s first winter. They found rock cairns that strangely contained no message indicating where the ships might have gone. At the end of summer most of the search ships stayed through the winter for another attempt the following summer.

Lady Jane Franklin differed with the Admiralty on the likely place to look for Franklin, pressing them to expand the search south of Lancaster Sound where the expedition originally intended to go. The Admiralty repeatedly sent expeditions to the north and west, even though they were unlikely to find Franklin by repeating the same mistake. It made no difference to her that on January 19, 1854 the British Government officially pronounced the men of the expedition dead. She was determined to find them dead or alive, in part to vindicate her husband as the one who completed the Northwest Passage. Lady Jane spent much of her personal money on three unsuccessful expeditions searching for her husband. She was frustrated that so many ships were sent in what she thought was the wrong direction.

Ultimately her intuition proved to be right. In 1857 Lady Jane arranged for Francis Leopold M’Clintock to sail the Fox, a ship she financed with £2,000 of her own money plus public subscription. M’Clintock knew the techniques for overland travel and survival in the Arctic, and his skills and persistence helped him learn what had happened to the Franklin expedition. In Part 3 we will see the ghastly outcome of M’Clintock’s search.