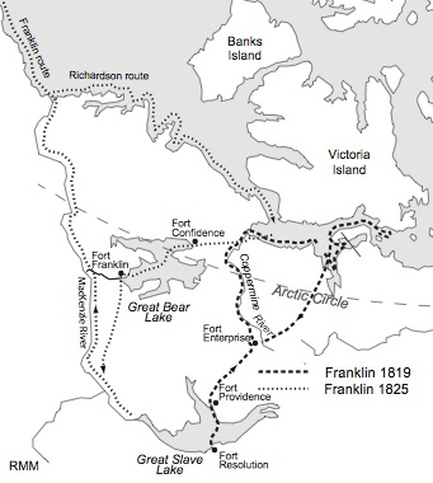

Franklin's routes for his first and second overland expeditions. Hudson Bay is off the map to the right.

Franklin's routes for his first and second overland expeditions. Hudson Bay is off the map to the right. In 1819 the Royal Navy undertook exploration of the Canadian Arctic, and the Admiralty selected Lieutenant John Franklin to command a land expedition to the uncharted Arctic coast. His instruction: trek overland on foot and by canoe from York Factory on Hudson Bay to determine the latitude and longitude of the north coast of North America and the trending of the coast both east and west. Franklin’s expedition was also directed to record temperature, wind and weather, the aurora borealis, and geomagnetic variations. They were to make drawings of the terrain, the natives, and other things of interest along the way.

First Expedition, 1819

Franklin was a naval officer with no experience canoeing, trekking in the tundra, hunting, or back-packing. The Admiralty simply assumed their officers could meet any demand. So they sent him into the wilds with little experience and a minimum of equipment. He was expected to travel five thousand miles by foot and canoe, picking up provisions at trading posts along the way. He was assured that arrangements for provisions had been made.

After only three months planning Franklin and twenty men departed in May, 1819 from York Factory on Hudson Bay. By October they reached Cumberland House trading post where they spent the winter. After the 1820 summer season of travel from Fort Resolution, across Great Slave Lake, and down the Coppermine River the party still had not reached the mouth of the river. Then a serious, unexpected problem arose. Provisions promised by the Hudson’s Bay Company had not been cached at their next winter quarters at Fort Enterprise and the Franklin party was forced to ration their remaining food.

In spring of 1821 they continued to the mouth of the Coppermine River. At the mouth of the river Franklin measured latitude and found the coast to be considerably farther south than Samuel Hearne had measured eighty-two years earlier (see Explorer’s Tales, 9/15/2014). Then the expedition proceeded eastward along the coast by canoe for several hundred miles before starting the return journey. By this time they were desperate for food and had great difficulty with their light-weight canoes traveling in the more turbulent coastal water.

For the return to Fort Enterprise they chose not to follow the river but instead struck off across the barren treeless tundra with no knowledge of the terrain ahead—in what proved to be a disastrous journey. They hoped the shorter more direct route would hasten them to winter quarters where provisions should be waiting. The party was nearly out of food and the winter gales began in early September. They were reduced to eating berries and lichen, hunted for an occasional deer to revive their energy, but also resorted to eating rotting deer carcasses found along the way. Eventually they were eating leather from their buffalo robes and boots. Because there was almost no wood on the tundra for fuel, most of what was eaten was uncooked. Franklin had a narrow escape when he fell into a torrential stream and later began to have fainting spells from exhaustion.

Franklin sent midshipman George Back ahead to find Indians that had agreed to help provide some food. On October 6, 1821 Franklin recorded that the party ate what was left of their old shoes (meaning moccasins of untanned leather) and any other leather they could find. They were now within a few days of Fort Enterprise where they expected to find a cache of food carried in over the summer by agents of the North West Company.

Several men stopped to rest because they were too weak to go on. Only Franklin, four voyageurs from the North West Company, and a handful of mariners reached Enterprise. Their intention was to take food and supplies to the men left behind. To their horror they found that no provisions had been brought to Fort Enterprise. All they found were some deerskins, which they roasted over a fire made from floorboards of the log house. For the next weeks they were kept alive on a diet of deer hide, lichen, and an occasional partridge bagged on their hunts.

Meanwhile at the camp of those left behind, arguments and shootings resulted in two men being killed. The survivors from that group arrived at Fort Enterprise only to find Franklin and the others in a sad state of emaciation.

Three Indians sent by George Back finally arrived in November with some meat. The starved group wolfed down the meat while the Indians built a fire and began caring for the starving men as though they were children. Franklin wrote that “the Indians treated us with the utmost tenderness, gave us their snowshoes, keeping by our sides that they might lift us if we fell.” Of the original party of twenty, eleven had died (two shot, nine starved)—a record held until his third expedition, which was far worse. In July, 1822 Franklin arrived safely in York Factory after having traveled 5,550 miles over land, river, and sea to map 350 miles of the north coast of North America. Franklin arrived home to public acclaim and became a hero. An admiring London press dubbed him, “The man who ate his boots.”

Second Expedition, 1825

Franklin made a second overland journey in 1825. This trip canoed down the Mackenzie River following the route of Alexander Mackenzie. At the mouth of the river his party split to survey the coast in both directions to connect with their previous survey in the east and to reach Icy Cape, Alaska, previously surveyed by Captain Cook in 1778, in the west. Dr. John Richardson, who had been on the first expedition as naturalist and surgeon, volunteered to conduct the survey of the eastern portion, and Franklin would lead the western survey. Lieutenant George Back, who had helped save the first expedition, was also selected for the second trip. That both Richardson and Back volunteered to go with Franklin again after the near disaster of the first trip is strong testimony to their confidence in him. Just as they prepared to leave Franklin received word that his ailing wife in England, Eleanor, had died from tuberculosis, and that one of his sisters looked after the baby, Eleanor. His wife of less than two years had urged him to go on this expedition despite her ill health. Although grieved by this loss, Franklin proceeded on the trip inland from York Factory.

This second trip was thoroughly planned and everything went well. No starvation, no deaths, and Franklin did not fall in the river. He had bigger and stronger canoes built to withstand travel and surveying along the coast near the surf. Provisions were provided along the way as planned. Although the eastern survey completed their objective, the western group, led by Franklin, ran into the end of the season before reaching his objective and turning back in August, 1826.

Although the trip was a success and no one died, it failed to capture the enthusiasm of the public as had the earlier more perilous and deadly journey. Mackenzie had already navigated the river to the coast and Franklin’s second expedition broke little new ground other than adding some coastline to the map. As the expedition suffered no serious hardships to achieve their goal, public interest was minimal. For his genuine achievements, however, John Franklin received honors. He was knighted in April, 1829, awarded an honorary doctorate from Oxford University, and received a gold medal from the Société de Géographie in Paris.

We will see in Part Two that Franklin’s third expedition, although carefully planned, had serious flaws leading to disaster. Some flaws resulted from inappropriate planning and equipment, and others from the mindset of the nineteenth century.

Sources

Berton, Pierre. The Arctic Grail: the Quest for the Northwest Passage and the North Pole, 1818-1909, New York:Viking Penguin, 1988.

Franklin, John. Narrative to the Shores of the Polar Sea, 1819, 1820, 1821, and 1822. London: John Murray, 1828.

Franklin, John. Narrative of a Second Expedition to the Shores of the Polar Sea in the Years 1825, 1826, and 1827, Includes John Richardson. Account of the Progress of a Detachment to the Eastward. Rutland: Charles E. Tuttle. 1971. First printed, 1828

McCoy. Roger M. On The Edge: Mapping North America’s Coasts. New York: Oxford University Press. 2012.