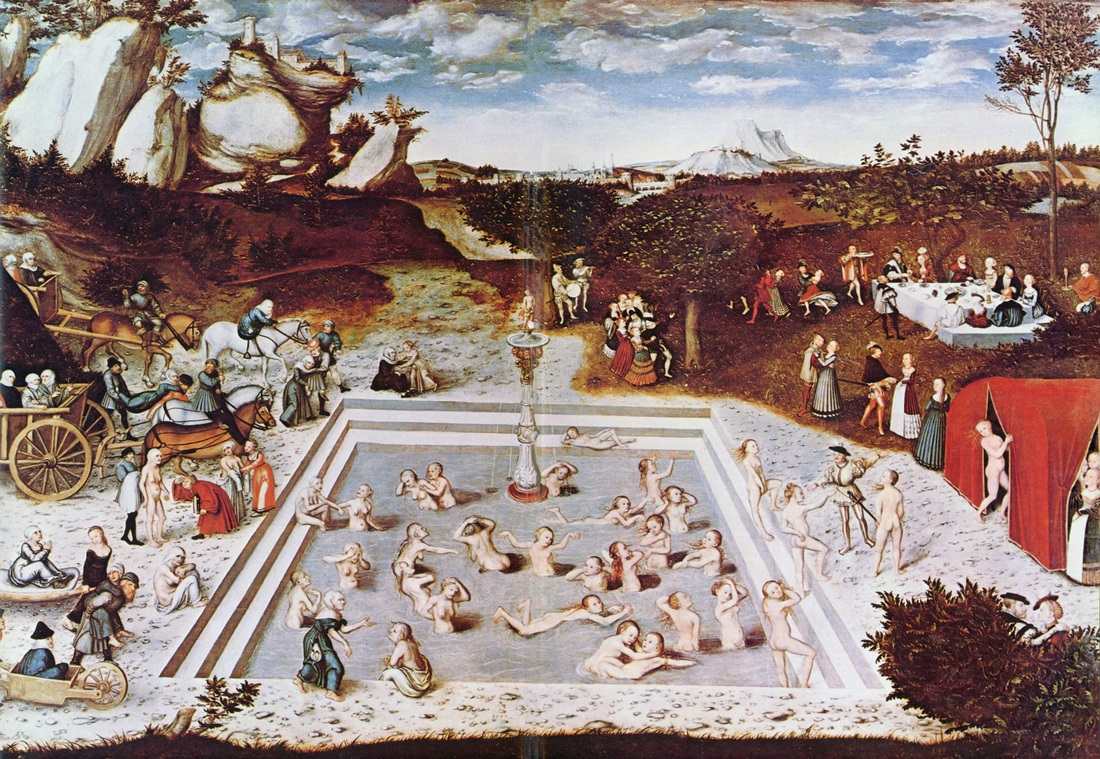

Cranach's depiction of the fountain of Youth, 1546. Wikipedia Commons

Cranach's depiction of the fountain of Youth, 1546. Wikipedia Commons Roger M McCoy

Tales, rumors, and myths about the rejuvenating power of waters from certain springs have appeared in writings as early as the fifth century B.C. Initially the location was an undefined Eurasian place where people retained a youthful virility indefinitely. Crusaders in the eleventh and twelfth centuries hoped to find such springs in their travels. A similar myth existed among the indigenous people of the New World, and arriving Europeans began to hear of a mystical island with youth-restoring waters.

In his history of the New World, sixteenth century historian Peter Martyr wrote that such waters existed north of Cuba on an island named Boiuca or Bimini, in “a spring of running water of such marvelous virtue that the water thereof being drunk, perhaps with some diet, makes old men young again.” It was said, moreover, that “on a neighboring shore might be found a river gifted with the same beneficent property.” Another historian, Antonio de Herrera, wrote in 1601 that an old man with barely enough strength to endure the journey was so completely restored as to resume “all manly exercises...take a new wife and beget more children.” Herrera added that natives had searched every “river, brook, lagoon, or pool” for a rejuvenating drink and bath in this miraculous water.

Underlying these myths was the eternal hope of avoiding death, but in the New World there was a strong element of hope among aging men to restore their failing sexual ability. The conquistadors in the New World apparently found a severe shortage of unicorn horn.

Then along came Juan Ponce de León, and every schoolchild learns that he looked for the Fountain of Youth. Although his real search was for wealth, especially from gold, his search for youth was an afterthought that became the main story. Ponce de León first came to the New World as one of 200 “gentleman volunteers” on the second voyage of Columbus in 1493. He and others left the expedition at the island of Hispaniola (the island occupied today by Haiti and Dominican Republic) with the hope of making their fortune there. Ponce de León assisted in a ruthless massacre and conquest of the native Taino kingdom of Higuey and was rewarded for his effort with a governorship of the Higuey Province in eastern Hispaniola.

As provincial governor Ponce de León had occasion to meet with the Tainos who visited his province from neighboring Puerto Rico. They told him stories of a fertile land with much gold to be found in the many rivers, and when he was shown a gold nugget from Puerto Rico he vowed to conquer it. With permission of the king of Spain he took a hundred soldiers ashore at Añasco Bay Puerto Rico in the summer of 1506. Within a year he subdued the Taino tribesmen living in the western half of the island with relatively little actual fighting. The Spanish crown confirmed his conquest by appointing him governor in 1509.

In Puerto Rico he soon realized his ambition of wealth by extorting gold from the Taino. Ponce de León parceled out the enslaved native Taínos among himself and other settlers using a system of forced labor. The natives were put to work growing food crops and mining for gold, and the Europeans grew wealthy. Variations of this abusive practice, repeated in many places, provides the unsavory conquistador aspect of Europeans’ arrival in the New World that casts a shadow over the present annual Columbus Day holiday. In the mindset of the sixteenth century European, however, there was nothing wrong with exploiting non-Christian populations.

Reports of great riches in lands to the north of Puerto Rico induced Ponce de León to obtain permission to find and claim the land of Bimini. The driving element in this new venture for Ponce de León himself was the agreement that he could keep one-tenth of all the wealth derived from his discoveries.

In March 1513 he sailed from Puerto Rico with three ships and 200 men. In early April he anchored offshore what he thought was an island and a most pleasant place. The banks of the inlet were filled with wild flowers in bloom and sent a fragrance to the ships. As Ponce de León made his claim, he named the land La Florida for its verdant growth, and also because it was then the Passover season called, Pascua Florida (Floral Passover). Ponce de León took possession in the name of King Ferdinand II of Aragon, who also just happened to be the king of Sicily, king of Naples, and king of Castile and León (It’s nice to be the king.)

One probable location of this landfall is believed to be far up on the Florida peninsula at an inlet near Daytona Beach about 50 miles south of St. Augustine. In the process of trying to return and sail south they encountered a current so strong that it pushed them backwards and forced them to seek anchorage. Their smallest ship was carried away and lost for two days. The expedition had accidentally found the Gulf Stream. For later European ships returning from the Caribbean, the Gulf Stream gave a useful boost northward into the westerly wind belt. The expedition sailed around the south end of Florida and the Keys and up the west coast as far as Charlotte Harbor.

On a second voyage to Florida in 1521 Ponce de León included a large contingent of settlers intending to establish a farming colony. An attack from native Calusa tribesmen fatally wounded Ponce de León, and the colonists abandoned the site. Ponce de León was buried in Puerto Rico.

Although stories of vitality-restoring waters were known on both sides of the Atlantic long before Ponce de León, the story that he was searching for the Fountain of Youth did not appear until after his death. While he may well have heard of the Fountain myth and believed in it, his name was not associated with the legend until later writings. The connection was made in Oviedo’s Historia General y Natural de las Indias of 1535, in which Oviedo wrote that Ponce de León was looking for the waters of Bimini to regain youthfulness. Gradually his real objective of finding gold was replaced with the more romantic sounding search for the Fountain of Youth.

References

Horowitz, Tony. A voyage long and Strange: Rediscovering the New World. New York: Henry Holt & Co. 2008.

Morison, S. E. The European discovery of America: The northern voyages, New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.