The success of any expedition, today or 500 years ago, depended upon a supply of food adequate for the rigors of travel at sea or in the wilds of North America. The hard labor of sailing or trekking required high calorie food with sufficient nutrients to maintain good health. This was no easy task in the sixteenth century as may be seen in the list of foods consumed daily. For example, the ships of the Frobisher expedition in 1577 included the following daily allowance per person: one pound of biscuit (hardtack); one gallon of beer; one-quarter pound of butter, one-half pound of cheese; one pound of salt beef or pork on meat days, plus one dried codfish for every four men on fast days; oatmeal and rice were loaded as back-up in case the fish supply ran out. In addition, the ship carried a hogshead (64 gallon barrel) of cooking oil; and a pipe (equal to two hogsheads) of vinegar for cooking purposes, and many bags of dried peas. Fishing line and hooks were taken to supplement the provisions, but not all places on the ocean have plentiful fish. On land the sailors would hope to find some deer or birds to hunt. Although some ships carried livestock to butcher along the way, Frobisher’s voyages had no extra room for animals and their fodder. This quantity of food for fifty men per ship plus extra sails, spars, rope, tar, firewood and water, required all the storage space. Even with this large amount of food there was always danger of severe losses from spoilage, leakage, or consumption by rats.

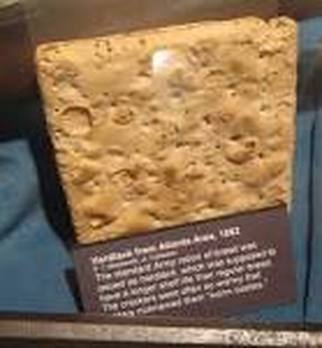

Hardtack, which was their primary carbohydrate, was simply unleavened flour and water, its main advantage was a very long shelf life. The hard dry biscuit had to be moistened with water or beer to make it easier to chew. Usually it already contained weevils even before it was loaded onto the ship, because it was made months in advance and stored. A typical meal for seamen might be: salted meat with peas porridge, consisting of dried fish in a thick mixture of pea soup, accompanied, of course, by a weevily biscuit. This may sound wholesome enough, but as the weeks went by the meat might have spoiled, the butter turned rancid, the beer turned sour, and the biscuits could be reduced to dust by weevils.

Overland journeys were somewhat different. The food had to be packed into smaller containers that could be carried by humans or pack animals. This put a greater reliance on hunting and foraging along the way. Some overland explorers learned so well from the native people that they could travel with minimal provisions and rely primarily on hunting to feed the entire party.

The Samuel Hearne expedition (see blog of Sept 15) traveled on foot with a group of Chipewyans from Hudson Bay to the shore of the Arctic Ocean. He wrote that one of his preferred recipes was,

“...a dish called beeatee, which is most delicious. It is made of blood, a good quantity of fat, (shredded small), some of the tenderest flesh, and the heart and lungs torn into small slivers. All this is put in the deer’s stomach and roasted by being suspended before the fire. When it is sufficiently done it will emit steam, which is as much to say, “Come eat me now!”

Another dish Hearne described was definitely not for squeamish eaters.

“The most remarkable dish known to both the Northern and Southern Indians is made of blood mixed with half-digested food found in the deer’s stomach, and is boiled to the consistency of pease-porridge [thick pea soup]. Some fat and scraps of tender flesh are also boiled with it. To render this dish more palatable, they have a method of mixing the blood with the stomach contents in the paunch itself, and then hanging it up in the heat and smoke near the fire for several days. This puts the whole mass in a state of fermentation, and gives it such an agreeable acid taste, that were it not for prejudice, it might be eaten by those with the nicest palates.

"Some people with delicate stomachs would not be persuaded to partake of this dish if they saw it being prepared, for most of the fat is first chewed by the men and boys in order to break the globules, so that it will all boil out and mingle with the broth. To do it justice, however, to their cleanliness in this particular, I must observe that old people with bad teeth had no hand in preparing this dish.”

Hearne also described the Indians’ method of preparing tripe from the stomachs of deer or buffalo.

“The tripe of the buffalo is exceedingly good and the Indian method of preparing it is infinitely superior to that of the Europeans. They will wash it clean in cold water and strip off the honeycomb and boil it for half or three-quarters of an hour. In that time it is rather tougher than what is prepared in England, but is more pleasant to the taste.”

Few overland expeditions were more thoroughly documented than that of Lewis and Clark in 1804-06, and their extensive journals have been mined for many kinds of information about almost everything. Their food is of particular interest as they chose to carry large quantities of staple items. Because the Lewis and Clark expedition was a U.S. government operation and the two leaders were army officers, it is useful to note what the army considered standard fare for a soldier. In 1787 the Congress made a law defining the basic ration for a soldier. The standard daily ration included one pound of bread, one pound of beef or 3/4 pound of pork, and one gill (4 oz.) of rum. The mainstay of army diet was bread with soup or stew, and beans. The bread was usually unleavened wheat or corn bread. It was understood that an army on the move must rely on foraging, hunting, and fishing for additional food while in the field.

Lewis and Clark took 193 pounds of something they called “portable soup,” which was made by boiling down beef, buffalo, or deer meat with eggs and vegetables to a thick paste, to be used when no other food was available. Perhaps they added water to make a soup. Another staple on their journey was “parchmeal,” made by heating corn kernels until they swell (like corn nuts), then grinding them into meal. Parching corn serves two purposes: 1) heating the corn prevented sprouting and hence spoilage, 2) parching separated the kernel from the hull, which could then be removed by winnowing. Another preparation of corn for backcountry travel involved soaking the kernels in a mixture of water and wood ash (lye) to produce hominy and grits.

The Lewis and Clark expedition carried 1220 pounds of parchmeal, along with 3400 pounds of flour, 560 pounds of biscuit (hardtack), 750 pounds of salt, 3705 pounds of pork, 112 pounds of sugar, 100 pounds of beans and peas, 70 pounds of lard, and 600 pounds of grease (tallow).

The monotony of corn, beans, and hardtack was broken when fresh meat or fruits and berries could be gathered along the way by the hunters in the group. When meat was plentiful and time available they made jerky or pemmican, which is made by pulverizing dried meat and mixing it with tallow. Given the obvious lack of fruits and vegetables in their diets, it was necessary to brew spruce tea whenever possible for the prevention of scurvy.

A major breakthrough in food preservation and storage came with the advent of canning in 1809. This innovation, more than any other, allowed ships to stay over the winter while exploring the Arctic. The story of canning began with a prize offered by the French government under Napoleon to anyone finding a way to preserve food for the army. Some of his military defeats hinged on insufficient food, which forced his army to disperse in order to better forage the countryside. Success, whether for armies or explorers, depends greatly on food.

References

Hearne, Samuel. A journey from Prince of Wales Fort in Hudson’s Bay to the Northern Ocean. Toronto: The Champlain Society. 1911.

McCoy, Roger M. On the edge: Mapping North America’s coasts. New York: Oxford University Press. 2012.

McIntosh, Elaine Nelson. The Lewis and Clark expedition: Food, nutrition, and health. Sioux Falls: The Center for Western Studies. 2003.