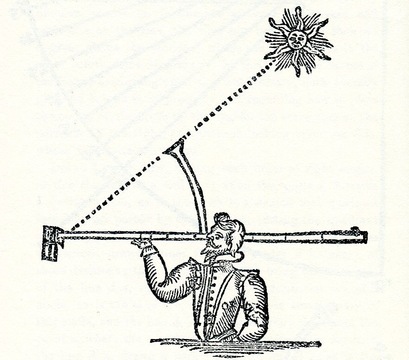

Illustration of the Davis Backstaff from his "Seaman's Secrets."

Illustration of the Davis Backstaff from his "Seaman's Secrets." Roger M. McCoy

Queen Elizabeth I was the first of the Tudors to give a major emphasis to exploration of the New World. Although Henry II had made an effort by sending John Cabot to the discovery of Newfoundland in 1497, he sanctioned no voyages of discovery afterwards. Elizabeth’s reign, however, was noted for it’s skilled mariners/privateers, i.e. sanctioned by the queen to capture and plunder enemy ships.

Elizabethan navigators such as Francis Drake, Martin Frobisher, Walter Raleigh, and Humfrey Gilbert each had a great deal of publicity connected with their exploits, discoveries, wars, and plunder. But in fact each of them could be considered failures in that they failed at their intended objectives. Raleigh’s attempted colony in Virginia failed. Frobisher’s “Northwest Passage” turned out to be an elongated bay, and his shiploads of “gold bearing” rocks, brought home at great cost, proved useless. Gilbert fell short in various ways by failing to make an intended settlement due to an under-provisioned expedition, then running his ship aground with the loss of most of his crewmen, then later managing to sink a ship with all hands. Drake succeeded handsomely in the plunder business, and had a shining reputation as a master mariner, but as an explorer he broke little new ground. A common trait among these mariners, however, was their distinctive panache. Each had a flamboyant style with a powerful self-confidence. Probably, this characteristic contributed much to their fame.

Another Elizabethan mariner, John Davis, although less well

known, also contributed little by his exploration, but he added greatly to navigational science of his day. Unfortunately, the passion of the 1580’s was finding the Northwest Passage. This futile effort doomed scores of expeditions to failure in a task that was as premature as space flight would have been.

Davis, like Drake, was from Devonshire. Although born in 1543, there is little known of him until 1579, when, at the age of thirty-six, he gave up a career as a privateer and undertook a series of three voyages in search of the Northwest Passage. Davis became associated with a group formed by Adrian Gilbert, brother of Humfrey, for the purpose of initiating a search for the Passage. In 1585 the queen granted a patent to Adrian Gilbert and associates allowing them to sail northeastward, northward, or northwestward with as many ships as they chose. They were given a monopoly of trade with newly discovered regions and rights of governmental powers if they created a colony. In short, they could do almost anything they wanted and be handsomely rewarded if successful. It was under this authority that John Davis, already an accomplished navigator and sea captain, made three voyages to the only remaining area where there might be a passage: the Arctic.

His chosen ships were the Sunneshine (50 tons, 23 crew, including a four-man orchestra) and Mooneshine (35 tons, 19 crew). After struggling against strong westerly winds the two ships sailed up the west coast of Greenland to an inlet at the present site of Nuuk (formerly Godthåb). There they decided to entice the natives with their four-piece orchestra.

This led to a scene that was no doubt the most unusual sight the Greenland Inuits had ever witnessed. The crew began announcing their presence by making a “lamentable noyse with great outcryes and skreechings like the howling of wolves.” Then another boat landed with more men and the four-piece orchestra, which played while the officers and sailors danced. As the Inuit’s kayaks approached, the sailors “ allured them by friendly embracings and signes of curtesie.” Not surprisingly, these antics did not induce the Inuits to draw closer. Then the master of the Mooneshine, who deemed himself an expert on communication with native people, began striking his chest and pointing to the sun. In case you cannot imagine the meaning of this peculiar gesture, take comfort knowing it probably baffled the Inuits as well. The sailors then placed some stockings, caps, and gloves on the ground as gifts, and danced and sang their way into their boats and rowed back to the ships as fiddlers fiddled.

Apparently this strange behavior worked as intended. The next day the Inuit arrived and transacted five kayaks, several sealskin parkas, and boots. After a day of successful trading, the expedition sailed west across the icy waters now called Davis Strait and discovered a wide and deep sound that Davis felt certain was the opening to the Northwest Passage. They sailed for miles into the new waterway (now Cumberland Sound in Ellesmere Island). It was August 20th and wintry winds convinced Davis and his officers that they risked spending the winter icebound. Then like Cabot and Frobisher, Davis turned back one day before reaching the point that would have proved the waterway not to be the Passage. He was wise to turn back. Cumberland Sound was often frozen by late summer during the 16th to 19th centuries.

Finding a waterway that could possibly be the Passage was always a good hook for funding the next voyage. Davis applied the hook with this statement full of errors and wishful thinking: “the northwest passage is a matter nothing doubtful, but at any tyme almost to be passed, the sea navigable, void of yse, the ayre tolerable and the waters very depe.”

The next year (1586) Davis was back with four ships, but for some unknown reason he passed by the opening to Cumberland Sound without recognizing it. This is especially strange because he made an accurate calculation of latitude at the mouth of the sound, but sailed on anyway. He sailed south all the way to the coast of Labrador, even passing the opening of Hudson Bay. The biggest discovery of the voyage was a “mightie store” of cod caught in the waters east of Labrador.

Despite this second failure, Davis sailed a third time by successfully convincing his investors that the passage “must be in one of four places, or els not at all.” This time (1587) Davis noticed a large opening to the west (Hudson Bay) and commented at length about a “furious overfall (tide-rip) lothsomly crying like the rage of waters under London bridge. We passed by a great gulfe, the water whirling and roaring as it were the meetings of tydes.” Indeed, a tidal bore flows from Hudson Bay at certain times, and Davis took this current to be the result of tides from the Oriental Sea. The current flowing from the opening was strong enough that large icebergs passed him even though he was under full sail. Davis fails to explain why he did not explore this great gulf. Probably heavy ice floes deterred him.

Davis again returned to England with a heavy load of Newfoundland cod and a promising report of yet another likely passage to the Oriental Sea. He never returned to investigate the “furious overfall,” but Henry Hudson used it to promote his final voyage (see earlier blog on Henry Hudson).

Davis lacked the flair of Drake and other Elizabethan navigators, and unlike his cohorts, he was never knighted. His voyages added little to the maps of the day and failed totally in their objective of finding the Northwest Passage. He is often mentioned for having sailed to the opening of Lancaster Sound, which is the true opening to the Passage, but he never considered it significant. Of course, it too was probably blocked by ice when he was there. This is actually no reflection on Davis; the Passage was not traversed successfully for more than 300 years when Roald Amundsen did it over several seasons (1903-1906).

Davis gave up exploration to become a chief pilot for the East India Company, and on one of these voyages he was killed in 1605 by a pirate he had just captured near Singapore.

Although his exploration voyages came to nothing, Davis contributed significantly by his improvement of navigation instruments...a subject for some future blog. His backstaff provided greater accuracy than the cross-staff, and allowed a mariner to measure solar angles with his back to the sun. Also, Davis published a much needed two volume book, Seaman’s Secrets, which established procedures and standards for navigation that benefitted all mariners of his time.

References

Davis, John, introduction and notes by A. H. Markham, The voyages and works of John Davis the navigator, New York: Burt Franklin (Originally published by Hakluyt Society First Series No. 59).

Morison, S. E., The European discovery of America: The northern voyages, New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Queen Elizabeth I was the first of the Tudors to give a major emphasis to exploration of the New World. Although Henry II had made an effort by sending John Cabot to the discovery of Newfoundland in 1497, he sanctioned no voyages of discovery afterwards. Elizabeth’s reign, however, was noted for it’s skilled mariners/privateers, i.e. sanctioned by the queen to capture and plunder enemy ships.

Elizabethan navigators such as Francis Drake, Martin Frobisher, Walter Raleigh, and Humfrey Gilbert each had a great deal of publicity connected with their exploits, discoveries, wars, and plunder. But in fact each of them could be considered failures in that they failed at their intended objectives. Raleigh’s attempted colony in Virginia failed. Frobisher’s “Northwest Passage” turned out to be an elongated bay, and his shiploads of “gold bearing” rocks, brought home at great cost, proved useless. Gilbert fell short in various ways by failing to make an intended settlement due to an under-provisioned expedition, then running his ship aground with the loss of most of his crewmen, then later managing to sink a ship with all hands. Drake succeeded handsomely in the plunder business, and had a shining reputation as a master mariner, but as an explorer he broke little new ground. A common trait among these mariners, however, was their distinctive panache. Each had a flamboyant style with a powerful self-confidence. Probably, this characteristic contributed much to their fame.

Another Elizabethan mariner, John Davis, although less well

known, also contributed little by his exploration, but he added greatly to navigational science of his day. Unfortunately, the passion of the 1580’s was finding the Northwest Passage. This futile effort doomed scores of expeditions to failure in a task that was as premature as space flight would have been.

Davis, like Drake, was from Devonshire. Although born in 1543, there is little known of him until 1579, when, at the age of thirty-six, he gave up a career as a privateer and undertook a series of three voyages in search of the Northwest Passage. Davis became associated with a group formed by Adrian Gilbert, brother of Humfrey, for the purpose of initiating a search for the Passage. In 1585 the queen granted a patent to Adrian Gilbert and associates allowing them to sail northeastward, northward, or northwestward with as many ships as they chose. They were given a monopoly of trade with newly discovered regions and rights of governmental powers if they created a colony. In short, they could do almost anything they wanted and be handsomely rewarded if successful. It was under this authority that John Davis, already an accomplished navigator and sea captain, made three voyages to the only remaining area where there might be a passage: the Arctic.

His chosen ships were the Sunneshine (50 tons, 23 crew, including a four-man orchestra) and Mooneshine (35 tons, 19 crew). After struggling against strong westerly winds the two ships sailed up the west coast of Greenland to an inlet at the present site of Nuuk (formerly Godthåb). There they decided to entice the natives with their four-piece orchestra.

This led to a scene that was no doubt the most unusual sight the Greenland Inuits had ever witnessed. The crew began announcing their presence by making a “lamentable noyse with great outcryes and skreechings like the howling of wolves.” Then another boat landed with more men and the four-piece orchestra, which played while the officers and sailors danced. As the Inuit’s kayaks approached, the sailors “ allured them by friendly embracings and signes of curtesie.” Not surprisingly, these antics did not induce the Inuits to draw closer. Then the master of the Mooneshine, who deemed himself an expert on communication with native people, began striking his chest and pointing to the sun. In case you cannot imagine the meaning of this peculiar gesture, take comfort knowing it probably baffled the Inuits as well. The sailors then placed some stockings, caps, and gloves on the ground as gifts, and danced and sang their way into their boats and rowed back to the ships as fiddlers fiddled.

Apparently this strange behavior worked as intended. The next day the Inuit arrived and transacted five kayaks, several sealskin parkas, and boots. After a day of successful trading, the expedition sailed west across the icy waters now called Davis Strait and discovered a wide and deep sound that Davis felt certain was the opening to the Northwest Passage. They sailed for miles into the new waterway (now Cumberland Sound in Ellesmere Island). It was August 20th and wintry winds convinced Davis and his officers that they risked spending the winter icebound. Then like Cabot and Frobisher, Davis turned back one day before reaching the point that would have proved the waterway not to be the Passage. He was wise to turn back. Cumberland Sound was often frozen by late summer during the 16th to 19th centuries.

Finding a waterway that could possibly be the Passage was always a good hook for funding the next voyage. Davis applied the hook with this statement full of errors and wishful thinking: “the northwest passage is a matter nothing doubtful, but at any tyme almost to be passed, the sea navigable, void of yse, the ayre tolerable and the waters very depe.”

The next year (1586) Davis was back with four ships, but for some unknown reason he passed by the opening to Cumberland Sound without recognizing it. This is especially strange because he made an accurate calculation of latitude at the mouth of the sound, but sailed on anyway. He sailed south all the way to the coast of Labrador, even passing the opening of Hudson Bay. The biggest discovery of the voyage was a “mightie store” of cod caught in the waters east of Labrador.

Despite this second failure, Davis sailed a third time by successfully convincing his investors that the passage “must be in one of four places, or els not at all.” This time (1587) Davis noticed a large opening to the west (Hudson Bay) and commented at length about a “furious overfall (tide-rip) lothsomly crying like the rage of waters under London bridge. We passed by a great gulfe, the water whirling and roaring as it were the meetings of tydes.” Indeed, a tidal bore flows from Hudson Bay at certain times, and Davis took this current to be the result of tides from the Oriental Sea. The current flowing from the opening was strong enough that large icebergs passed him even though he was under full sail. Davis fails to explain why he did not explore this great gulf. Probably heavy ice floes deterred him.

Davis again returned to England with a heavy load of Newfoundland cod and a promising report of yet another likely passage to the Oriental Sea. He never returned to investigate the “furious overfall,” but Henry Hudson used it to promote his final voyage (see earlier blog on Henry Hudson).

Davis lacked the flair of Drake and other Elizabethan navigators, and unlike his cohorts, he was never knighted. His voyages added little to the maps of the day and failed totally in their objective of finding the Northwest Passage. He is often mentioned for having sailed to the opening of Lancaster Sound, which is the true opening to the Passage, but he never considered it significant. Of course, it too was probably blocked by ice when he was there. This is actually no reflection on Davis; the Passage was not traversed successfully for more than 300 years when Roald Amundsen did it over several seasons (1903-1906).

Davis gave up exploration to become a chief pilot for the East India Company, and on one of these voyages he was killed in 1605 by a pirate he had just captured near Singapore.

Although his exploration voyages came to nothing, Davis contributed significantly by his improvement of navigation instruments...a subject for some future blog. His backstaff provided greater accuracy than the cross-staff, and allowed a mariner to measure solar angles with his back to the sun. Also, Davis published a much needed two volume book, Seaman’s Secrets, which established procedures and standards for navigation that benefitted all mariners of his time.

References

Davis, John, introduction and notes by A. H. Markham, The voyages and works of John Davis the navigator, New York: Burt Franklin (Originally published by Hakluyt Society First Series No. 59).

Morison, S. E., The European discovery of America: The northern voyages, New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.