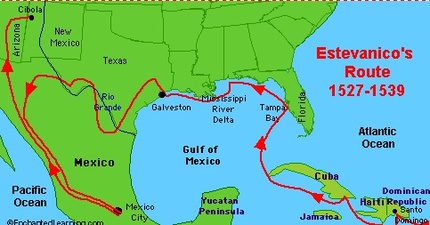

Esteban's route. Image from Enchanted Learning

Esteban's route. Image from Enchanted Learning Roger M McCoy

In school we learned about Francisco Vázquez de Coronado making his expedition north from Mexico, through what is now Arizona, New Mexico, and into Kansas in search of the legendary seven golden cities of Cibola in 1540-42. What we may not have learned is that an African slave was sent ahead a year earlier to investigate the rumors of wealthy cities to the north of New Spain. Only if the slave found evidence supporting the alluring stories would Coronado then follow to claim and conquer.

The story begins when Spanish slavers captured a young man on the northwest coast of Africa in the early sixteenth century. There was nothing unusual about this except that the young man was especially intelligent and talented. He was eventually purchased by a Spaniard named Andrés Dorantes who was soon to embark in 1527 on an ill-fated expedition of discovery to the New World led by Pánfilo de Narváez. The young slave, now named Esteban (Estevanico in some sources), proved to be an invaluable asset when the party eventually met disaster.

The expedition's mandate was to conquer and govern the lands and peoples along the Gulf of Mexico from the Florida Peninsula to the modern state of Tamaulipas in Mexico. The unfortunate troop suffered one setback after another, the worst being a storm that destroyed one of Narváez’s ships and damaged others. In mid-April the five ships, with a complement of some 300 men and forty-two horses that survived the trip, finally dropped anchor on the western coast of Florida, just north of Tampa Bay.

Their ensuing experience rivals the ancient saga of the Argonauts, involving battles with the natives, capture, enslavement, escape, near starvation, and overland trekking all the way to Mexico. Eventually the company of 300 was reduced to four men; the slave Esteban, his owner Dorantes, Cabeza de Vaca who wrote the only record of their odyssey, and one of the group captains named Alonzo del Castillo. During this long journey to Mexico Esteban became adept with native languages. He learned to present himself as a gifted shaman adorned with sea shells on his arms, feathers on his head, bright colored clothing, and a rattle made from a dried gourd. Esteban became known as a healer among the Indians and soon had a following of natives with headaches and other ailments. His success in healing the sick brought favor to Esteban and his three European companions although they often were prisoners of the Indians. During their time among the Indians the men heard fascinating tales of cities of great wealth to the north. There are several other examples of Indians telling explorers about great wealth someplace farther on—probably in an effort to induce them to leave. Finally after eight years and a long and difficult journey the four men arrived in Mexico.

When the survivors met Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza in Mexico City their stories of wealthy indigenous tribes to the north created great interest. Spaniards in New Spain had visions of finding another rich trove like that of the Aztecs. But Cabeza de Vaca and the other two Spanish companions had had enough of expeditions and declined to lead another. Dorantes and Cabeza de Vaca returned to Spain at the first opportunity. Before leaving New Spain Dorantes either gave or sold Esteban to Viceroy Mendoza, who described the slave as a very intelligent man. The viceroy decided to send Esteban as guide for an expedition to find the cities of Cibola under the leadership of the Franciscan brother, Marcos de Niza. Esteban was guide, scout, and interpreter with instructions to obey Brother Marcos.

Setting out on March 7, 1539 the two men and a party of hired Indians headed north. After two weeks Brother Marcos decided to send Esteban ahead on his own to reconnoiter the area. My guess is that Marcos had little stomach for the rigors of exploration. Marcos told Esteban to send a cross by messenger if wealth was discovered. If moderate wealth was discovered Esteban should send a cross of one palma (the span of outstretched fingers or about eight inches), a cross of two palmas would indicate somewhat greater wealth. If Esteban found wealth comparable to that of New Spain, he should send a very large cross. I think this code was necessary because Esteban, for all his language skills, was probably unable to write and oral communication with an Indian messenger was unreliable.

After about a week Esteban sent back a cross the size of a man with the report that Indians had told him of spectacular cities farther ahead. Esteban could not possibly have seen a golden city and the large cross was certainly sent on the basis of hearsay. When Brother Marcos saw the cross, Cibola seemed to be at hand and he immediately began the trek to reconnect with Esteban. Before he could reach Esteban’s location, however, Brother Marcos suddenly received the shocking word that Esteban was dead.

It has been presumed that Esteban was at the site of Zuni, New Mexico when he was killed. (Location is labelled Cibola on map above.) While it is certain that he had seen no cities of gold, it is not known why he was killed. One speculative idea is that Esteban displayed his gourd rattle with its owl feathers and began his act as a traveling shaman. The owl feathers, among other things, may have been his undoing—according to Zuni beliefs, the owl was representative of death. Esteban’s striking appearance and unfamiliar skin color plus the symbol of death hanging around his neck probably greatly alarmed the Zuni. The local shaman saw the trappings as those of distant enemy tribes, declared Esteban to be a devil sent to destroy them, and demanded he be put to death.

Whatever the reason, upon hearing this frightening news Brother Marcos, having no soldiers for protection immediately returned to Mexico City. Based on his sketchy second-hand reports of spectacular places ahead, Marcos easily convinced the viceroy that the rumored golden cities of the north might actually exist. Encouraged by these tales, the viceroy sent the explorer and would-be conquistador Coronado north a year later full of confidence in finding hoards of gold. But like Esteban and Marcos, Coronado found no gold.

This story is one of many concerning heroic searches attempting to prove a myth. The story of Cibola has roots hundreds of years earlier in the middle ages—before the New World was known. Its effective hook in explorer’s minds lay in the promise of wealth somewhere beyond the horizon.

Goodwin, Robert, Crossing the continent, 1527-1540: The Story of the First African-American Explorer of the American South. New York: Harper Perennial, 2009.

Flint, Richard and Shirley C. Flint, Esteban the Moor, retrieved from newmexicohistory.org/people/esteban-the-moor, (date not given).

In school we learned about Francisco Vázquez de Coronado making his expedition north from Mexico, through what is now Arizona, New Mexico, and into Kansas in search of the legendary seven golden cities of Cibola in 1540-42. What we may not have learned is that an African slave was sent ahead a year earlier to investigate the rumors of wealthy cities to the north of New Spain. Only if the slave found evidence supporting the alluring stories would Coronado then follow to claim and conquer.

The story begins when Spanish slavers captured a young man on the northwest coast of Africa in the early sixteenth century. There was nothing unusual about this except that the young man was especially intelligent and talented. He was eventually purchased by a Spaniard named Andrés Dorantes who was soon to embark in 1527 on an ill-fated expedition of discovery to the New World led by Pánfilo de Narváez. The young slave, now named Esteban (Estevanico in some sources), proved to be an invaluable asset when the party eventually met disaster.

The expedition's mandate was to conquer and govern the lands and peoples along the Gulf of Mexico from the Florida Peninsula to the modern state of Tamaulipas in Mexico. The unfortunate troop suffered one setback after another, the worst being a storm that destroyed one of Narváez’s ships and damaged others. In mid-April the five ships, with a complement of some 300 men and forty-two horses that survived the trip, finally dropped anchor on the western coast of Florida, just north of Tampa Bay.

Their ensuing experience rivals the ancient saga of the Argonauts, involving battles with the natives, capture, enslavement, escape, near starvation, and overland trekking all the way to Mexico. Eventually the company of 300 was reduced to four men; the slave Esteban, his owner Dorantes, Cabeza de Vaca who wrote the only record of their odyssey, and one of the group captains named Alonzo del Castillo. During this long journey to Mexico Esteban became adept with native languages. He learned to present himself as a gifted shaman adorned with sea shells on his arms, feathers on his head, bright colored clothing, and a rattle made from a dried gourd. Esteban became known as a healer among the Indians and soon had a following of natives with headaches and other ailments. His success in healing the sick brought favor to Esteban and his three European companions although they often were prisoners of the Indians. During their time among the Indians the men heard fascinating tales of cities of great wealth to the north. There are several other examples of Indians telling explorers about great wealth someplace farther on—probably in an effort to induce them to leave. Finally after eight years and a long and difficult journey the four men arrived in Mexico.

When the survivors met Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza in Mexico City their stories of wealthy indigenous tribes to the north created great interest. Spaniards in New Spain had visions of finding another rich trove like that of the Aztecs. But Cabeza de Vaca and the other two Spanish companions had had enough of expeditions and declined to lead another. Dorantes and Cabeza de Vaca returned to Spain at the first opportunity. Before leaving New Spain Dorantes either gave or sold Esteban to Viceroy Mendoza, who described the slave as a very intelligent man. The viceroy decided to send Esteban as guide for an expedition to find the cities of Cibola under the leadership of the Franciscan brother, Marcos de Niza. Esteban was guide, scout, and interpreter with instructions to obey Brother Marcos.

Setting out on March 7, 1539 the two men and a party of hired Indians headed north. After two weeks Brother Marcos decided to send Esteban ahead on his own to reconnoiter the area. My guess is that Marcos had little stomach for the rigors of exploration. Marcos told Esteban to send a cross by messenger if wealth was discovered. If moderate wealth was discovered Esteban should send a cross of one palma (the span of outstretched fingers or about eight inches), a cross of two palmas would indicate somewhat greater wealth. If Esteban found wealth comparable to that of New Spain, he should send a very large cross. I think this code was necessary because Esteban, for all his language skills, was probably unable to write and oral communication with an Indian messenger was unreliable.

After about a week Esteban sent back a cross the size of a man with the report that Indians had told him of spectacular cities farther ahead. Esteban could not possibly have seen a golden city and the large cross was certainly sent on the basis of hearsay. When Brother Marcos saw the cross, Cibola seemed to be at hand and he immediately began the trek to reconnect with Esteban. Before he could reach Esteban’s location, however, Brother Marcos suddenly received the shocking word that Esteban was dead.

It has been presumed that Esteban was at the site of Zuni, New Mexico when he was killed. (Location is labelled Cibola on map above.) While it is certain that he had seen no cities of gold, it is not known why he was killed. One speculative idea is that Esteban displayed his gourd rattle with its owl feathers and began his act as a traveling shaman. The owl feathers, among other things, may have been his undoing—according to Zuni beliefs, the owl was representative of death. Esteban’s striking appearance and unfamiliar skin color plus the symbol of death hanging around his neck probably greatly alarmed the Zuni. The local shaman saw the trappings as those of distant enemy tribes, declared Esteban to be a devil sent to destroy them, and demanded he be put to death.

Whatever the reason, upon hearing this frightening news Brother Marcos, having no soldiers for protection immediately returned to Mexico City. Based on his sketchy second-hand reports of spectacular places ahead, Marcos easily convinced the viceroy that the rumored golden cities of the north might actually exist. Encouraged by these tales, the viceroy sent the explorer and would-be conquistador Coronado north a year later full of confidence in finding hoards of gold. But like Esteban and Marcos, Coronado found no gold.

This story is one of many concerning heroic searches attempting to prove a myth. The story of Cibola has roots hundreds of years earlier in the middle ages—before the New World was known. Its effective hook in explorer’s minds lay in the promise of wealth somewhere beyond the horizon.

Goodwin, Robert, Crossing the continent, 1527-1540: The Story of the First African-American Explorer of the American South. New York: Harper Perennial, 2009.

Flint, Richard and Shirley C. Flint, Esteban the Moor, retrieved from newmexicohistory.org/people/esteban-the-moor, (date not given).