Roger M McCoy

France had already entered the land rush with Verrazzano, 1524, but did nothing to develop those discoveries (see Explorers Tales entry, 5/1/14). Their interest instead became focussed ten years later on the exploration of Jacques Cartier, a master mariner from St. Malo, France.

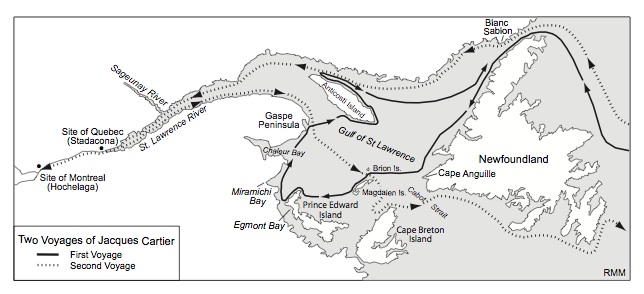

First Voyage, 1534

Cartier began his first voyage with two ships and 120 men in May, 1534. His instructions: find a passage to China and discover precious metals. Coincidentally he made the same landfall in Newfoundland as John Cabot and Leif Ericsson. He sailed south between the east coast of Labrador and Newfoundland Island, where he commented on the abundance of mosquitoes and flies. Sorry to say, those critters are still there.

Cartier’s report had nothing good to say about Labrador. He saw no promise for settlement because most places had no soil—just bare rock scraped clean by Pleistocene glaciers. Cartier referred to it as “the land God gave Cain.”

On the south shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Cartier began to describe a much more appealing landscape; one which showed potential for settlement. Here he told of the “best soil that ever we saw...full of goodly trees, meadows, fields full of wild corn.” He continued, “About the said island are very great beasts as great as oxen, which have two great teeth in their mouths like unto an elephant’s teeth, and live also in the sea (i.e.walruses).”

Here Cartier had his first encounter with Indians of the Micmac tribe. As many as fifty canoes appeared in the bay, with men shouting and waving pelts in the air. Cartier’s men felt threatened and fired a gun over the Indians’ heads to frighten them away. This was not a good start with the locals but the next encounter, one day later, went much better. When the Indians again appeared, Cartier sent men ashore with trading items, including knives, other tools, and a red cap for their chief. They returned to the ship laden with furs.

Near the head of Gaspé Bay, Cartier raised a cross thirty feet tall among an audience of Huron Indians. The words VIVE LE ROI DE FRANCE were inscribed with a plaque showing the fleurs-de-lys. Then all the crewmen knelt on the ground and raised their arms to heaven. Cartier had taken possession of these lands for France. The chief of the Hurons, sensing something significant had occurred to his domain, was not pleased and came aboard the ship to let Cartier know that this was his land and the cross had been erected without permission. Cartier must have handled this potentially explosive situation with proper diplomacy, as the chief was soon mollified. The chief came to regard Cartier so highly that he gave him two of his sons to take back to France on the condition they would be returned on the next voyage. The boys were quickly dressed in European clothing, and the expedition headed back to France without yet having entered the St. Lawrence River.

At home Cartier found he had become a man of status. In one voyage of five months he had claimed and mapped most of the lands around Gulf of St. Lawrence and saw promising open water to the west, suggesting a sea route through the continent. Actually he saw only the sixty-mile-wide mouth of the St Lawrence River that penetrates deep into North America.

Second Voyage, 1635

Cartier returned the next summer with three ships and the two Indian boys as guides and interpreters, and sailed up the St Lawrence River. Their guides told them they were entering the kingdom of Saguenay along a great river. The news that they were on a river of fresh water and not a sea route to China must have disappointed Cartier, and he now faced the choice of returning to France with little to report or staying for the winter. He decided it would be far better to stay than to return with nothing. They may be the first Europeans after the Norse to winter in the cold climes of North America.

The Indian guides told him that this area marked the beginning of the country they called Canada. The boys may have used the term Canada to mean their settlement and its environs, but Cartier understood it to mean a much larger region. At the site of present day Quebec hundreds of Huron-Iroquois Indians lived in a settlement called Stadacona.

When word spread that the white men had returned with the two sons, many canoes converged on the ship. When the sons told the chief of the wonderful things they had seen in France, the chief put his arms around Cartier’s neck to express his welcome, and period of peaceful relations began.

The Indians of Stadacona attempted to dissuade Cartier from continuing farther upstream to the settlement of Hochelaga. They put on a big display of a devil-like figure appearing in a canoe with a message that Cartier and his men would all die if they went farther. The ruse failed, and Cartier sailed with one small ship and fifty men up river to Hochelaga.

Arriving at the site of the present day city of Montreal, then the head of navigation on the St. Lawrence, Cartier wrote that a thousand Indians came to the shore, leaping and singing in a welcoming greeting with offerings of fish and cornbread. The site of Hochelaga lies near a mountain which Cartier named Mont Royal, still a prominent landmark in Montreal.

The Hurons of Hochelaga brought diseased, crippled, and blind men asking Cartier to touch them as if he had godly powers to heal. Rising to the occasion, Cartier read from the Gospel of John, and as he touched each man he prayed that these people might receive Christ. The Indians sat silently and imitated Cartier’s gestures. Cartier then gave gifts to all, including women and children and returned to Stadacona for the winter.

A disastrous scourge of scurvy hit both Indian and French populations in the winter of 1535-36. By December, eight of Cartier’s men had died and fifty more lay at the point of death. Only three or four men, including Cartier, had not yet been struck by the disease. One day a woman brought some tree branches with instruction to boil them and drink the liquid twice a day. The recovery of the French sailors was so rapid that Cartier declared it to be a miracle. All the sailors were restored to health. The tree in question was probably the Eastern Arborvitae, a tree rich in vitamin C.

Chief Donnacona had told Cartier so many tales of odd races of humans that lived beyond their country—men without stomachs, and men that had only one leg, that Cartier thought the chief himself should tell these incredible stories to King Francis I. Unfortunately he failed to mention his idea to the chief, and when Donnacona came on board, Cartier suddenly made prisoners of the chief and his men. This created a great uproar, both among both the captive Indians and the people standing on shore. Cartier promised to return them all the next year. Given their good relations up to that time, Donnacona might have agreed without coercion to go to France.

Third Voyage, 1541

The final voyage had the single purpose of establishing a settlement of Frenchmen at Stadacona. However, Cartier was reduced to a subordinate role under the king’s friend, Jean François de la Roque de Roberval, who was to be the governor of the settlement rather than Cartier.

Cartier sailed on May 23, 1541 with five ships as an advance party, and Roberval’s ship departed a year later. Cartier found the Indians eagerly awaiting their long missing chief Donnacona. Unfortunately Donnacona and all his fellow captives except a little girl had died in France. This created a very awkward moment which Cartier handled by telling the gathering that Donnacona had indeed died, but all the other captives had become wealthy lords in France, and chose not to return. The new chief of Stadacona was apparently pleased with this news.

The Indians soon cooled to the idea of the French living there permanently and gave the French cause to fear an attack. By the end of winter Cartier decided his part of the agreement as an advance party was ended, and he set sail for home in June, 1542, leaving a precarious colony behind. The next year the struggling settlement was abandoned due to illness and continued hostility of the Indians. Cartier never made another voyage and spent the rest of his days on his estate near St. Malo until his death in 1557 at age sixty-five.

References

Green, Meg. Jacques Cartier: Navigating the St Lawrence River. New York: Rosen Publishing Group, 2004.

Leacock, Stephen. The Mariner of St. Malo. Toronto: Glasgow, Brook and Company, 1920.

McCoy, Roger M., On the Edge: Mapping North America’s Coasts, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Morison, S. E. The European discovery of America: The northern voyages, New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

France had already entered the land rush with Verrazzano, 1524, but did nothing to develop those discoveries (see Explorers Tales entry, 5/1/14). Their interest instead became focussed ten years later on the exploration of Jacques Cartier, a master mariner from St. Malo, France.

First Voyage, 1534

Cartier began his first voyage with two ships and 120 men in May, 1534. His instructions: find a passage to China and discover precious metals. Coincidentally he made the same landfall in Newfoundland as John Cabot and Leif Ericsson. He sailed south between the east coast of Labrador and Newfoundland Island, where he commented on the abundance of mosquitoes and flies. Sorry to say, those critters are still there.

Cartier’s report had nothing good to say about Labrador. He saw no promise for settlement because most places had no soil—just bare rock scraped clean by Pleistocene glaciers. Cartier referred to it as “the land God gave Cain.”

On the south shore of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Cartier began to describe a much more appealing landscape; one which showed potential for settlement. Here he told of the “best soil that ever we saw...full of goodly trees, meadows, fields full of wild corn.” He continued, “About the said island are very great beasts as great as oxen, which have two great teeth in their mouths like unto an elephant’s teeth, and live also in the sea (i.e.walruses).”

Here Cartier had his first encounter with Indians of the Micmac tribe. As many as fifty canoes appeared in the bay, with men shouting and waving pelts in the air. Cartier’s men felt threatened and fired a gun over the Indians’ heads to frighten them away. This was not a good start with the locals but the next encounter, one day later, went much better. When the Indians again appeared, Cartier sent men ashore with trading items, including knives, other tools, and a red cap for their chief. They returned to the ship laden with furs.

Near the head of Gaspé Bay, Cartier raised a cross thirty feet tall among an audience of Huron Indians. The words VIVE LE ROI DE FRANCE were inscribed with a plaque showing the fleurs-de-lys. Then all the crewmen knelt on the ground and raised their arms to heaven. Cartier had taken possession of these lands for France. The chief of the Hurons, sensing something significant had occurred to his domain, was not pleased and came aboard the ship to let Cartier know that this was his land and the cross had been erected without permission. Cartier must have handled this potentially explosive situation with proper diplomacy, as the chief was soon mollified. The chief came to regard Cartier so highly that he gave him two of his sons to take back to France on the condition they would be returned on the next voyage. The boys were quickly dressed in European clothing, and the expedition headed back to France without yet having entered the St. Lawrence River.

At home Cartier found he had become a man of status. In one voyage of five months he had claimed and mapped most of the lands around Gulf of St. Lawrence and saw promising open water to the west, suggesting a sea route through the continent. Actually he saw only the sixty-mile-wide mouth of the St Lawrence River that penetrates deep into North America.

Second Voyage, 1635

Cartier returned the next summer with three ships and the two Indian boys as guides and interpreters, and sailed up the St Lawrence River. Their guides told them they were entering the kingdom of Saguenay along a great river. The news that they were on a river of fresh water and not a sea route to China must have disappointed Cartier, and he now faced the choice of returning to France with little to report or staying for the winter. He decided it would be far better to stay than to return with nothing. They may be the first Europeans after the Norse to winter in the cold climes of North America.

The Indian guides told him that this area marked the beginning of the country they called Canada. The boys may have used the term Canada to mean their settlement and its environs, but Cartier understood it to mean a much larger region. At the site of present day Quebec hundreds of Huron-Iroquois Indians lived in a settlement called Stadacona.

When word spread that the white men had returned with the two sons, many canoes converged on the ship. When the sons told the chief of the wonderful things they had seen in France, the chief put his arms around Cartier’s neck to express his welcome, and period of peaceful relations began.

The Indians of Stadacona attempted to dissuade Cartier from continuing farther upstream to the settlement of Hochelaga. They put on a big display of a devil-like figure appearing in a canoe with a message that Cartier and his men would all die if they went farther. The ruse failed, and Cartier sailed with one small ship and fifty men up river to Hochelaga.

Arriving at the site of the present day city of Montreal, then the head of navigation on the St. Lawrence, Cartier wrote that a thousand Indians came to the shore, leaping and singing in a welcoming greeting with offerings of fish and cornbread. The site of Hochelaga lies near a mountain which Cartier named Mont Royal, still a prominent landmark in Montreal.

The Hurons of Hochelaga brought diseased, crippled, and blind men asking Cartier to touch them as if he had godly powers to heal. Rising to the occasion, Cartier read from the Gospel of John, and as he touched each man he prayed that these people might receive Christ. The Indians sat silently and imitated Cartier’s gestures. Cartier then gave gifts to all, including women and children and returned to Stadacona for the winter.

A disastrous scourge of scurvy hit both Indian and French populations in the winter of 1535-36. By December, eight of Cartier’s men had died and fifty more lay at the point of death. Only three or four men, including Cartier, had not yet been struck by the disease. One day a woman brought some tree branches with instruction to boil them and drink the liquid twice a day. The recovery of the French sailors was so rapid that Cartier declared it to be a miracle. All the sailors were restored to health. The tree in question was probably the Eastern Arborvitae, a tree rich in vitamin C.

Chief Donnacona had told Cartier so many tales of odd races of humans that lived beyond their country—men without stomachs, and men that had only one leg, that Cartier thought the chief himself should tell these incredible stories to King Francis I. Unfortunately he failed to mention his idea to the chief, and when Donnacona came on board, Cartier suddenly made prisoners of the chief and his men. This created a great uproar, both among both the captive Indians and the people standing on shore. Cartier promised to return them all the next year. Given their good relations up to that time, Donnacona might have agreed without coercion to go to France.

Third Voyage, 1541

The final voyage had the single purpose of establishing a settlement of Frenchmen at Stadacona. However, Cartier was reduced to a subordinate role under the king’s friend, Jean François de la Roque de Roberval, who was to be the governor of the settlement rather than Cartier.

Cartier sailed on May 23, 1541 with five ships as an advance party, and Roberval’s ship departed a year later. Cartier found the Indians eagerly awaiting their long missing chief Donnacona. Unfortunately Donnacona and all his fellow captives except a little girl had died in France. This created a very awkward moment which Cartier handled by telling the gathering that Donnacona had indeed died, but all the other captives had become wealthy lords in France, and chose not to return. The new chief of Stadacona was apparently pleased with this news.

The Indians soon cooled to the idea of the French living there permanently and gave the French cause to fear an attack. By the end of winter Cartier decided his part of the agreement as an advance party was ended, and he set sail for home in June, 1542, leaving a precarious colony behind. The next year the struggling settlement was abandoned due to illness and continued hostility of the Indians. Cartier never made another voyage and spent the rest of his days on his estate near St. Malo until his death in 1557 at age sixty-five.

References

Green, Meg. Jacques Cartier: Navigating the St Lawrence River. New York: Rosen Publishing Group, 2004.

Leacock, Stephen. The Mariner of St. Malo. Toronto: Glasgow, Brook and Company, 1920.

McCoy, Roger M., On the Edge: Mapping North America’s Coasts, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Morison, S. E. The European discovery of America: The northern voyages, New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.