Roger M McCoy

Part 1 To see Part 2 click here.

We may read accounts of early explorers sailing to unknown lands in the New World, but we seldom learn details about their ships or about the life of a sailor on those small caravels and carracks.

To become a sailor a boy started as an apprentice no later than age fourteen. The boy’s parents, if they had the means, paid a ship’s master or first mate a hefty sum to train the boy for up to nine years as an unpaid apprentice. In return the ship’s master would see that the boy learned everything about sailing. Boys with such training could expect rapid advancement after the apprenticeship ended, and could anticipate becoming a first mate or a ship’s master by their mid-twenties.

Boys from poor families could be accepted without a payment to the ship’s master, but there would be little hope of advancing above the level of able seaman after the apprenticeship. Without a payment the boy often became little more than the master’s servant. Whether wealthy or poor, apprentices were bound to years of unpaid service to the ship’s master. After the apprenticeship, they began to receive some wages, which were paid in a lump at the end of a voyage.

A sailor’s work included many different tasks. Before starting a voyage any ship needed some repair from her previous voyage. Masts, sails, and hull may have been damaged and required refurbishing— replacing masts or yards, sewing up sails. Also the constant strain from wind against the masts and waves battering the hull weakened joints between boards on the decks and hull, requiring extensive scraping, re-caulking, and tarring. Even the best of ships had leaky hulls and required frequent pumping of the bilge. These tasks filled a sailor’s time in preparation for a voyage and continued throughout the time at sea.

As the time neared for departure sailors loaded and stowed the food, water, and other ship’s stores. Besides food, provisions included all the necessary supplies: candles, firewood, brooms, buckets, rope, pots and pans, tools, beer, wine, and dozens of items needed for self-sufficiency during the voyage. Sometimes the ship’s carpenter had to build stalls and coops for pigs, chickens, sheep, or cattle.

The food provided for the English explorer Martin Frobisher’s second voyage to North America in 1577 was considered sufficient for 120 men for up to four months. Included in the food list on Frobisher’s ship were: one pound of biscuit (known as hardtack) per man per day; one gallon of beer per man per day; one pound of salt beef or pork per man on meat days, plus one dried codfish for every four men on fast days; oatmeal and rice were loaded as back-up in case the fish supply ran out; one quarter-pound of butter and one half-pound of cheese per man per day; honey (sugar was still a rare luxury then); a hogshead (64 gallon barrel) of cooking oil; a pipe (equal to two hogsheads) of vinegar. These sailors ate and drank well, as they must with the amount of energy expended in their daily work. Upon reaching land they planned to hunt game animals and birds to supplement the meat supply. Also they carried fishing gear for periods of sailing in good fishing areas.

During a voyage there were always food losses from spoilage of both food and beer, and leakage from barrels. If fresh meat was supplied for the voyage it had to be eaten in the first few days. Livestock on board could make fresh meat later in the voyage as well, but explorer’s ships seldom made room for animals.

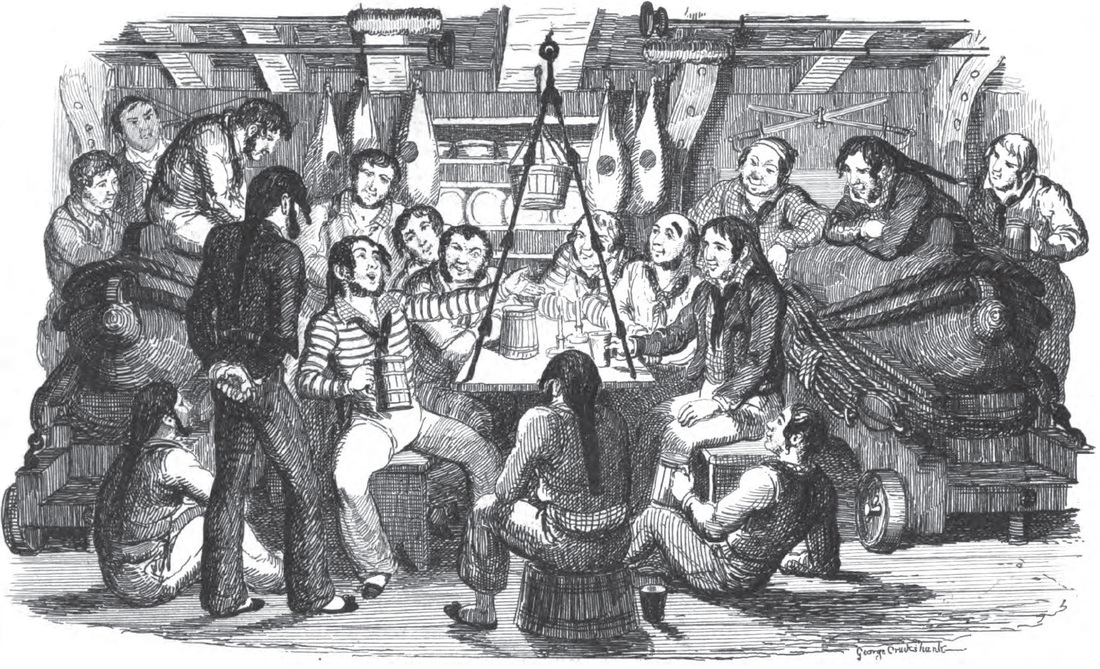

The main food staple was hardtack biscuit and its main advantage was that it had a very long shelf life. The hard, dry biscuit had to be moistened with water or beer to make it easier to chew. Typically the hardtack already had weevils even before it was loaded onto the ship because it was made months in advance. A typical menu for seamen might be: salted meat with pease porridge consisting of dried fish in a thick mixture of pea soup accompanied, of course, by a hardtack biscuit. Although this sounds like a wholesome meal, as the weeks went by the meat might spoil, the butter turn rancid, the beer go sour, and the many biscuits reduced to dust by the weevils. For drink the officers were usually provided with wine or spirits. Sailors in the English navy had a daily ration of beer, but French seamen often preferred fermented cider to beer. A cook-box was set up on a bed of sand or rocks below the forecastle, where sailors would go to get their bowls filled and eat wherever they could find a spot to sit. Some larger ships eventually began to provide a mess area where the crew could sit and eat.

While underway a sailor’s work held some real hazards, especially climbing the shroud lines up to the yards and standing on foot-ropes working thirty to fifty feet above the deck. Sails could be furled (rolling the sail up and securing it to the yard), reefed (shortening the sail to a length appropriate to the strength of the wind). A fall from the yard was almost always fatal whether the sailor fell into the sea or onto the deck. If he fell into the sea he usually drowned before the ship could rescue him. Normally there was little if any effort made to rescue, especially if the water was very cold as he would live only minutes. Often hazardous work needed to be done at night in the midst of a howling storm when the sails needed to be reefed or furled to compensate for the strong wind. This meant that sailors had to know the rigging well enough to work in total darkness with fingers numb from the cold. Work on the deck during a storm was almost as dangerous due to the chance of being washed overboard as the sea spilled onto the deck.

A sailor brought his sea chest aboard with clothing and a few personal items. His clothing usually consisted of a woolen pullover shirt with hood, woolen knee-length trousers with long woolen stockings, and a knitted cap. They had shoes, but often went barefoot to avoid slipping on decks and ropes. No clothing provision was made for bad weather unless the sailor brought it himself. Some sailors had up to six changes of clothing to allow for drying soaked clothes and to avoid sleeping in wet clothes. A few sailors might include a fiddle, fife, or tin whistle in their sea chest and provide some music for song and dance in idle times. By the early nineteenth century harmonicas and concertinas were common aboard ships.

During the sixteenth century sailors slept wherever they could find a vacant place on decks or cargo. Columbus saw natives in the Caribbean area sleeping in hammocks and some of his sailors adopted the idea, but hammocks were not widely used on ships until almost 100 years later. Cabins and bunks were provided for officers, but sailors often slept on the deck in the bow, or below in bad weather.

Reports of ships lost at sea without trace were real and frightening to men traveling the oceans. Such misfortunes were often believed to be the result some misbehavior of a crew member and a sailor might be ostracized for his deed. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (Coleridge, 1778) tells of a ship becalmed because a sailor committed the unforgivable blunder of killing an albatross and was forced to wear its carcass hung from his neck. This is the source of the expression “an albatross around my neck” to mean a great burden. Protection from dangers and misfortune was provided by the diligent practice of religion while at sea. Sailors keenly felt they were in the hands of the Almighty and made frequent prayers to God, the Virgin Mary, and patron saints for protection. In order to avoid any chance of offending God, many ship’s captains forbade swearing, blaspheming God, filthy stories, or any ungodly talk. Also gambling with dice or cards or fighting was forbidden on some ships. Morning and evening prayer services with readings from the Bible were often part of the required daily routine. Injunctions against foul language on board ships lasted through the nineteenth century.

Superstitions, sometimes mixed with the religion, also played a role. A ship should not begin a voyage on Friday because it was the day Christ was crucified. When building a ship a silver coin must be placed under the base of the main mast. One must never destroy a printed page as it might belong to the Bible. Many sailors were illiterate and could not be sure if a page might be from the Bible so they took the safe position that all printed pages were scripture. Some ship builders carried a burning fire brand through every part of a new vessel to drive out evil spirits.

The greatest danger aboard ships on long voyages in the sixteenth century was scurvy (see Explorer’s Tales, 3/15/2014). Any fresh fruits, vegetables, or fresh meat on board were soon consumed, and the rest of the voyage was dangerously deficient of vitamin C. After about six weeks of salted meat and hardtack the first symptoms could begin to appear—swelling of the gums and loosening of teeth, then blotches on the skin followed by a deep lethargy often leading to death. Consumption of food containing vitamin C could quickly correct all these symptoms—except for death.

Despite the dangers and risks sailors usually felt bonded to life at sea. Eric Newby told of both the dangers and the thrill of sailing when he wrote of his experience as a young crewman aboard a big square-rigged ship in 1938. Sometimes fearing for his life he wrote, “At this height, 130 feet up, in a wind blowing 70 miles an hour, the noise was an unearthly scream. ... the high whistle of the wind through the halyards, and above all the pale blue illimitable sky, cold and serene, made me deeply afraid and conscious of my insignificance.” However standing on deck on a fair day Newby described the joy of sailing. “As time passed, the ship possessed us completely. Our lives were given over to it. A hundred times a day each one of us looked aloft at the towering pyramids of canvas, the beautiful deep curves of the leeches of the sails and the straining sheets of the great courses, listened to the deep hum of the wind up the height of the rigging, the thud and judder of the steering gear as the ship surged along, heard the helmsman striking the bells, signaling a change of watch or a mealtime, establishing a routine so strong that the outside world seemed unreal.”

The sailor’s life was hard and once a man entered that life there was seldom a way out. Months at sea could be followed by periods of inactivity waiting for another voyage to begin. Even when countries had standing navies officers might be reduced to half pay during idle periods and ordinary seamen at no pay.

To read Part 2 of "Life at Sea in the 16th Century" click here.

Sources

Earle, Peter. Sailors: English Merchant Seaman 1650-1775. London: Methuen, 1998.

McCoy, Roger M. On the Edge, New York: Oxford. 2012.

Newby, Eric. The Last Grain Race. Hawthorn, Australia: Lonely Planet Publications, 1999.

Watson, Harold Francis. The Sailor in English Fiction and Drama 1550-1800. New York: Columbia University Press, 1931.