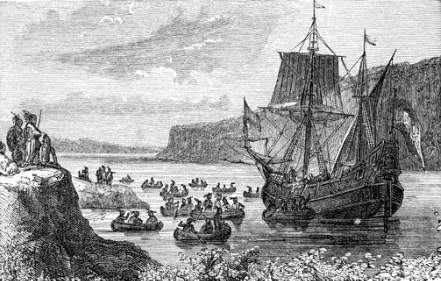

Hudson's ship, Halve Maen. Wikimedia Commons

Hudson's ship, Halve Maen. Wikimedia Commons By Roger M. McCoy

Henry Hudson envisioned that he would be the first explorer to find the elusive western passage through North America to the Orient. He persisted in this westward looking vision although his financier, the Dutch East India Company, insisted that he search eastward through the ice-bound sea north of Russia. Hudson had previously tried this northeastern route as well as a northerly route directly over the North Pole. Both had failed due to impassable ice.

On 25 March 1609, Hudson, an Englishman under contract with the Dutch, set sail in the Halve Maen (Half Moon). The Dutch, aware of Hudson’s belief in a westward passage, specified that he should not attempt a west route even if the eastern route proved impossible. Hudson had no interest in another failure, therefore it is not surprising that he soon found a good reason to end this effort, using the weather as the excuse. As might be expected along the west coast of Norway in late spring, the ship did encounter severe storms with gale force winds; but examination of the logs also shows much fair weather, raising doubts that weather actually forced him back. Rather than return to Amsterdam as instructed, Hudson turned west and later anchored in a bay on the coast of Nova Scotia. From there he sailed south as far as Chesapeake Bay, then turned and sailed north again.

On the third of September Hudson sighted an opening to a bay, which appeared to be the mouth of a large river. The next morning they entered what came to be known as New York Bay and dropped anchor. Soon “people of the country” came to the ship carrying trade goods and seemed glad to see the Europeans. They traded green tobacco, deer skins, and maize for knives and beads. He reported that the native people wore skins of foxes and other animals, and were “very civil.” Hudson also noted that the people had copper tobacco pipes, and he inferred that copper naturally existed in the area. Over the next two days other trading sessions took place. Hudson recorded the Indian name for a large island in the river as Manna-Hata.

On the sixth of September five crewmen were determining water depths by boat when they were attacked by natives in two canoes. One of the crewmen, John Colman, was killed by an arrow in the neck. When Indians came again with their trade goods, the ship’s crew captured two of them briefly, but set one free while the other jumped overboard. No more trading took place under these tense conditions.

Hudson weighed anchor on 13 September 1609 and began his exploration up the great river that still bears his name. He hoped this river might be a connection to the Orient. As the Halve Maen sailed up the river, Hudson wrote in his log, “It is as pleasant a land as one need tread upon; very abundant in all kinds of timber suitable for ship building and for making large casks or vats.” Sixty miles up the river they reported seeing many salmon. “Our boat went out and caught a great many very good fish.” Indians came to the ship and traded corn, pumpkins, and tobacco for what Hudson considered mere trifles, not knowing that the Indians saw these “trifles” as valuable for commerce among themselves.

Hudson wrote further on his impressions, “the land is the finest for cultivation that I have ever in my life set foot upon, and also abounds in trees of every description. The natives are very good people.” Regarding the agriculture of the natives, Hudson wrote that he saw enough maize and beans spread for drying to load three ships, in addition to the standing crops in the fields.

On the twenty-second of September they found the river too shallow to continue farther upstream, and in the vicinity of present day Albany they turned the ship for return to the sea. The ship’s log ends during the return crossing with a puzzling gap from the fifth of October to the seventh of November, when the Halve Maen docked in Dartmouth, England. There Hudson was detained by the Crown to prevent him from sailing again for the Dutch. After months of delay the Dutch portion of the crew continued to Amsterdam.

Henry Hudson failed in his quest for a passage through North America, as did many others. This third voyage, however, succeeded by claiming much of present day New York and parts of surrounding states for the Dutch, who began to settle the areas around New York Bay. The Dutch managed to hold their claim until 1674 when the land was ceded to the British.

Why did Hudson stop in England rather than Holland? There is no clear answer; perhaps he was avoiding repercussions for blatantly disregarding instructions. or perhaps the English component of the crew forced him to stop in England. The gap in the log might have shed light on this question. There are several known instances of dissent and mutiny among Hudson’s crews over his four voyages, the last one leading to his abandonment and disappearance with eight others on the shore of Hudson Bay in June 1611. Hudson’s greatest weakness was a leadership style that provoked his crews to mutiny, and in the end this weakness defeated his ambition for exploration.

Sources

Asher, George M. Henry Hudson the Navigator: The Original Documents in Which His Career is Recorded, Collected, Partly Translated, and Annotated. New York: Burt Franklin, Publisher, 1860.

Johnson, Donald S. Charting the Sea of Darkness: the Four Voyages of Henry Hudson. Camden, Maine: International Marine, 1993.

McCoy, Roger M. On the Edge: Mapping North America’s Coast. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

First appeared in Oxford University Press Blog 9/7/13

Henry Hudson envisioned that he would be the first explorer to find the elusive western passage through North America to the Orient. He persisted in this westward looking vision although his financier, the Dutch East India Company, insisted that he search eastward through the ice-bound sea north of Russia. Hudson had previously tried this northeastern route as well as a northerly route directly over the North Pole. Both had failed due to impassable ice.

On 25 March 1609, Hudson, an Englishman under contract with the Dutch, set sail in the Halve Maen (Half Moon). The Dutch, aware of Hudson’s belief in a westward passage, specified that he should not attempt a west route even if the eastern route proved impossible. Hudson had no interest in another failure, therefore it is not surprising that he soon found a good reason to end this effort, using the weather as the excuse. As might be expected along the west coast of Norway in late spring, the ship did encounter severe storms with gale force winds; but examination of the logs also shows much fair weather, raising doubts that weather actually forced him back. Rather than return to Amsterdam as instructed, Hudson turned west and later anchored in a bay on the coast of Nova Scotia. From there he sailed south as far as Chesapeake Bay, then turned and sailed north again.

On the third of September Hudson sighted an opening to a bay, which appeared to be the mouth of a large river. The next morning they entered what came to be known as New York Bay and dropped anchor. Soon “people of the country” came to the ship carrying trade goods and seemed glad to see the Europeans. They traded green tobacco, deer skins, and maize for knives and beads. He reported that the native people wore skins of foxes and other animals, and were “very civil.” Hudson also noted that the people had copper tobacco pipes, and he inferred that copper naturally existed in the area. Over the next two days other trading sessions took place. Hudson recorded the Indian name for a large island in the river as Manna-Hata.

On the sixth of September five crewmen were determining water depths by boat when they were attacked by natives in two canoes. One of the crewmen, John Colman, was killed by an arrow in the neck. When Indians came again with their trade goods, the ship’s crew captured two of them briefly, but set one free while the other jumped overboard. No more trading took place under these tense conditions.

Hudson weighed anchor on 13 September 1609 and began his exploration up the great river that still bears his name. He hoped this river might be a connection to the Orient. As the Halve Maen sailed up the river, Hudson wrote in his log, “It is as pleasant a land as one need tread upon; very abundant in all kinds of timber suitable for ship building and for making large casks or vats.” Sixty miles up the river they reported seeing many salmon. “Our boat went out and caught a great many very good fish.” Indians came to the ship and traded corn, pumpkins, and tobacco for what Hudson considered mere trifles, not knowing that the Indians saw these “trifles” as valuable for commerce among themselves.

Hudson wrote further on his impressions, “the land is the finest for cultivation that I have ever in my life set foot upon, and also abounds in trees of every description. The natives are very good people.” Regarding the agriculture of the natives, Hudson wrote that he saw enough maize and beans spread for drying to load three ships, in addition to the standing crops in the fields.

On the twenty-second of September they found the river too shallow to continue farther upstream, and in the vicinity of present day Albany they turned the ship for return to the sea. The ship’s log ends during the return crossing with a puzzling gap from the fifth of October to the seventh of November, when the Halve Maen docked in Dartmouth, England. There Hudson was detained by the Crown to prevent him from sailing again for the Dutch. After months of delay the Dutch portion of the crew continued to Amsterdam.

Henry Hudson failed in his quest for a passage through North America, as did many others. This third voyage, however, succeeded by claiming much of present day New York and parts of surrounding states for the Dutch, who began to settle the areas around New York Bay. The Dutch managed to hold their claim until 1674 when the land was ceded to the British.

Why did Hudson stop in England rather than Holland? There is no clear answer; perhaps he was avoiding repercussions for blatantly disregarding instructions. or perhaps the English component of the crew forced him to stop in England. The gap in the log might have shed light on this question. There are several known instances of dissent and mutiny among Hudson’s crews over his four voyages, the last one leading to his abandonment and disappearance with eight others on the shore of Hudson Bay in June 1611. Hudson’s greatest weakness was a leadership style that provoked his crews to mutiny, and in the end this weakness defeated his ambition for exploration.

Sources

Asher, George M. Henry Hudson the Navigator: The Original Documents in Which His Career is Recorded, Collected, Partly Translated, and Annotated. New York: Burt Franklin, Publisher, 1860.

Johnson, Donald S. Charting the Sea of Darkness: the Four Voyages of Henry Hudson. Camden, Maine: International Marine, 1993.

McCoy, Roger M. On the Edge: Mapping North America’s Coast. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

First appeared in Oxford University Press Blog 9/7/13