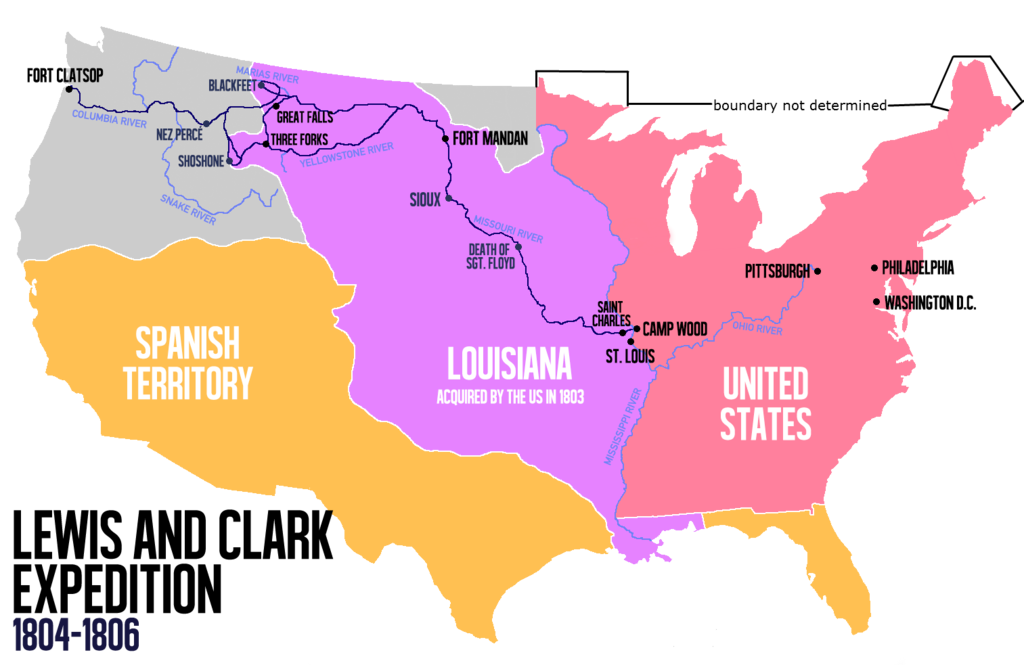

Route of the Corps of Discovery. Wikimedia Commons

Route of the Corps of Discovery. Wikimedia Commons Roger M McCoy

At the beginning of the nineteenth century little was known about the vast interior of the North American continent. When Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette explored the Mississippi in 1673 they passed the mouth of a large river coming from the west. Local natives told them that the river could take them to the western ocean. This bit of information led to the common knowledge that the Missouri River was the gateway to the west. Saint Louis still carries that theme with its giant arch symbolizing the gateway. In part, the early increase in North American exploration was tied to Napoleon’s misfortunes in Europe causing him to sell the Louisiana Territory to the United States in 1803 to raise money.

Years before Thomas Jefferson became president he was convinced that it would be very important to explore the interior of the continent, cross the distant mountains, and reach the Pacific by land. When Jefferson took office in 1801 he began planning a small expedition that would travel to the source of the Missouri, then portage their canoes and equipment a short distance, and float to the Pacific. His expectation for an easy portage was based on the experience of Alexander Mackenzie’s successful 1793 crossing of the Rockies in western Canada with a portage of only 800 paces. Jefferson owned a copy of Mackenzie’s report of that expedition. He felt the long term presence of British and French traders in the area was ample incentive for the Americans to also establish a presence in the territory.

Soon after taking office in 1801 Jefferson asked Meriwether Lewis, a young army officer already known to Jefferson, to become his personal secretary. It is believed that Jefferson had his eye on Lewis to lead an expedition. In 1801 the land he wanted to explore still belonged to France. While the United States was involved in negotiations with France in 1803 for access and free trade to the port of New Orleans, Napoleon unexpectedly offered the entire Mississippi watershed west of the river. Napoleon agreed to $15,000,000 for the entire land grant. In today’s dollars that would be in the neighborhood of $300,000,000…still a bargain. The new, unknown area more than doubled the size of the young United States. Now the planned expedition would not be trespassing on foreign land, they would be in American territory most of the way.

In January 1803 Congress approved initial funds of $2,500 for the expedition’s preparations, but by the time the it was ready to leave they had spent $35,000 (approximately $700,000 today). Lewis immediately contacted his friend and fellow army officer about going with him on the expedition and Clark quickly accepted, “My friend I do assure you that no man lives with whom I would prefer to undertake Such a Trip &c. as yourself.”

President Jefferson wrote a long statement of purpose for the expedition. In summary it was: to explore the Missouri River, to find its communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean for the purpose of commerce, and to make observations of longitude and latitude at permanent points along the rivers. All observations were to be written in a journal with several copies for security. Jefferson warned them to avoid all confrontation and to back off rather than fight in the interest of the success of the expedition. There was to be no warfare or claiming land in the name of the United States. As Commander-In-Chief, Jefferson’s instructions constituted a standing order.

Lewis had only eight months from the time funding was approved until they must embark from Pittsburgh on the journey to Saint Louis, which was to be their starting point the following spring. Then only twenty-nine years old, Lewis went to Philadelphia and visited the leading men of the time: experts in surveying for training with sextant and chronometer, botanists to learn the proper way of collecting and preserving plant specimens, geologists to learn identification of rocks, and physicians to learn how to treat ailments of his men and Indians along the way. President Jefferson had also written the appropriate men requesting the experts to meet with Lewis.

The medical expert was Benjamin Rush, a renowned Professor of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Rush was a man of remarkable achievements. He started the first post office, organized the first free schools for poor children, promoted education for women, and helped develop treatment for mental diseases. This man was especially knowledgable about the culture and diseases of Indians. In addition to teaching Lewis about ailments he might encounter in the wilderness, Rush gave Lewis a list of questions to inquire of the Indians regarding their health and medical practices, morals, and religion. After William Clark joined the expedition, Lewis had to teach him all the material. Lewis especially drilled Clark on survey methods so when separated they could still complete the all-important map.

Lewis acquired needed equipment, supplies, weapons, medicines, food, clothing, camping gear, scientific instruments, wood cutting and carpentry tools, and selected personnel. He arranged for the primary boat to be built and also a small collapsible boat. He arranged for everything to be shipped to the embarkation point in Pittsburgh PA at the beginning of the Ohio River. All this was completed between January and August using only the early-day postal service without the benefit of telephone, telegraph, or email. Arrangements were expedited as the President provided letters of instruction and introduction where needed.

Lewis planned to take only a small amount of food as they expected to exist by hunting and trading with the Indians. Following is a summary of his shopping list that included some 170 different items: scientific instruments, clothing, arms and ammunition, gifts for the Indians, boats, medicines, mosquito nets, 150 pounds of portable soup, and bags of dried grain. The so-called portable soup was a gelatin made by boiling cows’ hooves, adding vegetables, and then allowing it to gel for transport. Water and heating would revitalize it into a tasteless glop. This concoction was held in reserve for times of dire need.

Lewis bought 32 different medications. Keep in mind that the two major treatments for any ailment were bleeding and purging (laxatives, emetics, and enemas). The gastrointestinal tract must be thoroughly cleansed. Laxatives such as jalap, calomel (mercuric chloride), rhubarb, cream of tartar, Glauber's salts (sodium sulfate), magnesia, and nutmeg were used. He bought 5000 doses of these laxatives plus some pills prepared by Dr. Rush called Rush’s Thunderbolts. Emetics to induce vomiting included white vitriol (zinc sulfate), ipecac (from a plant root), and tartar. They also took 3000 doses of Peruvian bark (a source of quinine) in case of malaria, which never occurred. He acquired medications for fevers, snakebites, opium for pain relief, mercury and irrigating syringes for venereal diseases, and a Kinepox (cowpox) solution as a protection against smallpox. There were surprisingly few treatments for wounds: instruments for probing and extracting bullets or arrowheads, and material for dressing wounds but not for stitching. In the absence of antiseptics, wounds were best left open rather than being stitched closed. The medicines proved to be one of the most important items for developing smooth relations and trade with Indian tribes along the way.

Another important task was arranging for men to join the expedition, which Lewis called the Corps of Discovery. The personnel were primarily soldiers, but boatmen and hunters/interpreters were also hired. Altogether fifty-nine people participated in the expedition, but some went only as far as the first winter quarters in present day South Dakota, and a few others joined them in North Dakota for the trip westward.

Lewis bought an abundance of gifts for Indians (beads, calico shirts, colorful handkerchiefs, mirrors, scissors, thimbles, knives, fish hooks, combs, etc.), but there were not enough, and near the end of the expedition they were down to the last gifts and men had to bargain with their own clothes or for medical services. One of the notable gifts was a medal struck for the expedition, with clasped hands on one side and an impression of President Jefferson on the other side: large medals were for chiefs, smaller medals for other men.

They left Pittsburgh on August 30, 1803, arrived near Saint Louis on December 13th, and built log cabins for their winter quarters on the east shore of the Mississippi. The Corps of Discovery embarked from Saint Louis for their wilderness expedition on May 14, 1804 with plans to reach the North Dakota Territory before winter. Part Two will focus on their two winters at the Mandan villages in North Dakota and Fort Clatsop on the Pacific coast.

Sources

DeVoto, Bernard, The Journals of Lewis and Clark. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 1953.

Paton, Bruce C. M.D., Lewis and Clark: Doctors in the wilderness. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing. 2001.