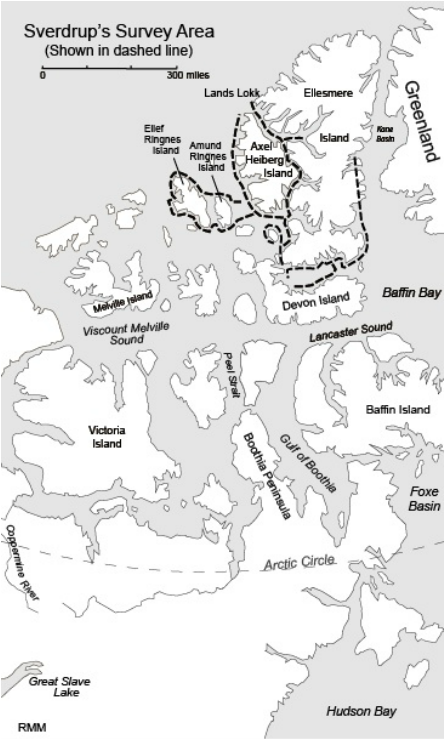

Canadian Arctic islands showing Sverdrup's survey area.

Canadian Arctic islands showing Sverdrup's survey area. Roger M McCoy

During the 400 hundred years before the end of the nineteenth century most Arctic exploration was motivated either by the search for a water passage through North America or by the search for Sir John Franklin. Most of the nineteenth century expeditions produced maps and scientific observations although their main motives were searching for passages or lost people. Between the years 1898 and 1902 a Norwegian named Otto Sverdrup undertook an expedition for the sole purpose of mapping very large areas of the Canadian Archipelago that were still unknown and for collecting scientific information.

At this time the hottest lure of the Arctic was not the Passage but the North Pole, already the object of several failed expeditions. But Sverdrup’s expedition involved no search for the Northwest Passage and no rush to the North Pole. In fact, Sverdrup regarded the race to the Pole as something akin to an international sports event and had no interest in playing that game. There was no glamour to his exploration project, just mapping and science. Sverdrup became known among Arctic explorers when he accompanied Fridjof Nansen as second in command on an odyssey of drifting with Arctic currents while purposely locked in the polar ice from 1893-1896. Nansen’s expedition hoped to drift to the North Pole, but failed to reach it. The Fram eventually emerged in the North Atlantic Ocean after starting offshore of Siberia.

When asked if he would lead an expedition in 1898, Sverdrup noted, “There are still many white spaces on the map which I was glad for the opportunity to color with the Norwegian colors, and thus the expedition was decided.” Canada claimed rights to all the islands already discovered by the British, but other countries still viewed the unclaimed areas as open for whalers and the claims of explorers. Thus Sverdrup acquired huge areas of land for Norway.

On this new venture Sverdrup commanded the Fram, the same ship that Nansen’s expedition used for drifting in the polar ice for nearly four years. It was a 128-foot, three-masted schooner with a shallow draft, strengthened hull, thick insulation, and rounded bow and stern for better maneuvering in ice-clogged water. The ship had an auxiliary steam engine and a crew of fifteen well-chosen men. When word spread that a seasoned explorer like Sverdrup was planning an expedition, applications arrived from many parts of the world. The group he selected included some experienced seamen to operate the ship, a Norwegian army cartographer, a Swedish botanist, a Danish zoologist, a Norwegian physician, and a Norwegian geologist. This was a model expedition, precisely planned and executed. In June, 1898, the expedition departed from Kristiansand, on the south coast of Norway and headed for Ellesmere Island to begin their work.

They remained in the area until 1902, during which time they traveled by dog sleds and mapped all the west coast of Ellesmere Island, the entire island of Axel Heiberg Land, and two islands, Ellef Ringnes and Amund Ringnes, which were named for two brothers who owned a brewing company and who had helped equip the expedition. Near the end of the expedition, Sverdrup reached the northernmost point on the west coast of Ellesmere, which he named Lands Lokk (Land’s End). The north coast of Ellesmere had previously been surveyed by Pelham Aldrich in 1878 while looking for a suitable starting point for the dash to the Pole as part of the Nares expedition. Robert Peary had also traversed the north coast of Ellesmere for the same reason.

Because Robert Peary had previously surveyed a piece of the north coast of the island, Sverdrup no doubt knew of him and knew that Peary had a driving ambition to become famous by being first to reach the North Pole. One day in 1898 Peary happened onto Sverdrup’s encampment on the east coast of Ellesmere, and assuming that Sverdrup was a competitor in the race to the Pole, Peary was cool and would not discuss anything lest he give away his intentions. He left abruptly and doubled his efforts northward to make certain that Sverdrup could not steal his glory. Sverdrup regarded the brief incident with amusement. Sverdrup himself was already well-known among Arctic explorers, so it is not too surprising that an ambitious person like Peary might view him as a competitor.

In 1904 Sverdrup wrote, with significant input from his colleagues, a two-volume narrative of the expedition—the English translation edition is titled New Land. The tone of the writing is upbeat and gives the impression of competent and brave men who relished their experience. He told the exciting experience of his second in command, Victor Baumann, on a survey of the west coast of Ellesmere Island. Baumann took some time to hunt musk oxen and suddenly found himself the target of a charging herd of thirty animals. The nature of the surrounding terrain and the speed of the charge left him no escape. His only options were to stand and be crushed, or to counter-charge the herd.

“The animals suddenly became aware of me, and wheeled right round and headed straight for me at a full gallop. So close on each other were their horns that they seemed to form an unbroken line. The animals sunk their heads until they almost touched the ground, and they snorted, blew, and puffed like a steam engine. There was no time for prayer or reflection. If this was to be the end of me then, in Heaven’s name, let me rush into it rather than standing still. So, with a horrible yell, and waving my arms, I charged the line. This did some good, for as I came nearer I saw the rank open, and I ran straight through it. The nearest animals were not a yard from me. Before I had time to think the whole herd wheeled round, coming towards me again, and I once more charged the line. As before the ranks opened, and I slipped through unscathed.”

Next the herd broke into smaller groups and began to come from all sides. Poor Baumann felt doomed this time. His dogs arrived on the scene in the nick of time and dispersed the herd long enough for him to escape.

After returning to Norway, Sverdrup’s team of scientists wrote thirty-five scholarly publications. Maps made during Sverdrup’s expedition became widely known, and he was given the Grand Cross of the Royal Norwegian Order of St. Olav, and a medal from the Royal Geographical Society. Norway honored Sverdrup for his achievements, but took little interest in their rights on the land he had mapped. The Canadian government, however, had a great interest in claiming all the lands of the Arctic Archipelago. In 1930 the Norwegian government ceded their claim of the islands to Canada. Sverdrup sold his maps and notes to the Canadians for $67,000 Canadian dollars, a handsome sum in 1930. Alas, two weeks later Sverdrup died at the age of seventy-six.

Source

Sverdrup, Otto. New Land. London: Longmans, Green and Company. 1904.