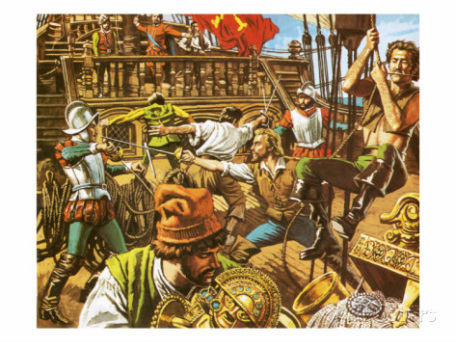

Francis Drake attacking a Spanish ship. Artist: Payne

Francis Drake attacking a Spanish ship. Artist: Payne

The 1577-1580 voyage for which Sir Francis Drake became famous in his time was intended to be a survey for the western terminus of a Northwest Passage, but was also sanctioned as a privateering venture against the Spanish on the west coast of the New World. He probably planned to return to England as he had come, through the Straits of Magellan. The voyage instead became the second circumnavigation of the world by European mariners and the richest haul of Spanish gold ever made.

As a youth, Drake apprenticed aboard a trading ship sailing from Plymouth. His adeptness in learning to sail put him in a command position by the time he was twenty. In addition to his sailing skills, Drake was skilled at painting wildlife, and would sometimes paint while at sea. A contempoary at the time of the big voyage described Drake as about thirty-six years old, short in stature, thickset, and very robust. He had a fine countenance, ruddy complexion and a fair beard. He had the mark of an arrow wound in his right cheek and carried a ball from an arquebus in one leg.

Drake’s voyage was financed by a syndicate of investors that included the well-known Sir Francis Walsingham, first secretary and advisor to Queen Elizabeth I. Drake himself put in £1,000. It is generally accepted that Drake began the voyage with a royal commission giving him legitimacy as a privateer, not a pirate. Nevertheless, the Spanish saw him as a pirate.

The fleet sailed from Plymouth with the Pelican and five other ships in December, 1577. Each ship was heavily armed with cannon and arquebuses. Grumbling from the crew along the way led to an unfortunate execution of one of the top officers, Thomas Doughty, whom Drake accused of fomenting a mutiny. By the time they left the coast of Brazil two ships had been lost in a storm and one had to be abandoned as unseaworthy. At this time Drake also changed the name of the Pelican to the Golden Hind, an unusual move in mid-voyage that some mariners considered to be unlucky.

The remaining ships entered the Straits of Magellan in August, 1578, with unusually favorable winds for that region. Drake made the 363 mile passage in just 16 days, Magellan had taken 37 days (in 1520). After his two other ships turned back when storm winds overpowered them while making the passage, Drake was now down to one ship, his Golden Hind. He sailed alone up the west coast of Chile looking for plunder and found aplenty.

The Spanish had built small settlements along the coast for accumulating gold and other resources to be picked up by unarmed Spanish coastal merchant ships. Because they considered themselves out of reach of raiders, most settlements were only lightly defended and the ships carried no cannon. Drake’s method was to surprise, capture, and sack a Spanish settlement and all the shipping in the harbor. When he had stowed everything of value he released all the ships and sailors, but took their sails to prevent pursuit.

The Spanish at the time labeled El Draque a cruel and ruthless pirate. But his victims gave an opposite account, reporting his humanity and generosity...a surprising assessment for someone who desecrated churches, stole their sacred vessels, and destroyed statues and paintings. His main redeeming trait was that of not allowing raping or killing in cold blood. Along the coast of Chile Drake attacked the settlements of Valparaiso, Coquimbo, and Valdiva, where his crew of 80 men captured over 1700 bottles of Chilean wine among its plunder.

Poor communication made it impossible for a ravaged village to warn other harbor settlements along the coast, so Drake was able to attack by surprise in every instance. In one sacked settlement Drake learned that a ship heavily loaded with riches was in Callao, the harbor town for Lima, Peru. There they looted a dozen or more ships with silver, gold (coin and plate), linen, and silk. The local authorities sent to Lima for help, but by the time 200 armed defenders arrived, Drake and his men were gone. No wonder that Drake became such a hero to the English, who loved nothing more than humiliating the Spanish.

Their next conquest was to be the biggest ever: Nuestra Señora de la Conceptión was a big ship fully loaded with treasure bound for Panama, where the cargo would be transported overland to the Atlantic coast for shipment to Spain. The Conceptión had the Spanish nickname Cacafuego (literally shitfire), which was a misnomer suggesting she was heavily armed with cannon, when in fact she was unarmed. Drake’s men merely came alongside and grappled. When the crew of the Cacafuego resisted, Drake loosed a volley of chain shot (several cannon balls connected by a chain designed for breaking masts) and severed the mizzen mast while about 40 men boarded and took possession. An important step at this time was for Drake to show the captured captain his commission from the queen proving that his actions were legitimate and sanctioned by the crown of England. Cold comfort to the vanquished! Drake told the captain, “Have patience, such is the usage of war,” and the next morning ate breakfast with him in a congenial manner. The entire crew of the Golden Hind entered into these attacks with the spirit of exuberant schoolboys. Drake himself became the very image of a swashbuckler in the style that actor Errol Flynn imitated in the 1930’s and 40’s (Captain Blood, 1935; Sea Hawk, 1940).

It took three days to transfer all the plunder to the Golden Hind. The booty from Cacafuego amounted to 80 pounds of gold, plus jewels, 13 chests full of plate, and 26 tons of silver. Before departing Drake gave gifts of coins, clothing, and weapons to each crewman of the Cacafuego. One captured Spanish captain wrote that Drake was one of the greatest living mariners, who treats his men with affection and the men show great respect for him.

Drake continued up the west coast, probably as far as Oregon, when cold winds induced him to head south. In California he found a secluded bay for much needed repairing of leaks and cleaning the hull of the Golden Hind. HIstorians have debated about the exact bay in question, with one faction supporting San Francisco Bay and others supporting one of several bays. The consensus of careful research now strongly favors Drakes Bay at the Point Reyes Peninsula north of San Francisco. Drake stayed in this location for five weeks, during which time the friendly and welcoming Miwok tribe offered Drake their symbols of respect: a mantle of skins, a wood scepter, and a cap with crown-like feathers. Drake interpreted these gestures as a sign the Indians wanted him to be their king. The Indians true intent is unknown, but Drake regarded this event as a feudal ceremony, declared them to be subjects of Queen Elizabeth I, and named the country Nova Albion. He chose the name because it embodied the white cliffs in the local area as well as being the earliest name of his native England.

Now finished with his stay in the New World, Drake knew the enraged Spanish would be waiting for him if he returned by the same route. So he made the bold decision to head west across the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and the Atlantic coast of Africa and Europe...being careful to avoid known Spanish sea routes. He reached Plymouth in September, 1580, almost three years after the beginning of his voyage.

The Golden Hind brought home more plunder than any ship before that time. The exact amount is uncertain, but the investors are believed to have received at least 1,000 percent on their investments, even after the queen extracted her generous share.

All this bounty made Francis Drake a rich man and a highly favored person in the queen’s court. The Spanish, on the other hand, petitioned the queen to punish Drake and return the spoils to Spain. Queen Elizabeth’s response was to knight Drake in a ceremony aboard the Golden Hind. This insult to King Philip II of Spain merely fed his passion for dethroning this illegitimate, protestant queen, and gave him further reason to send his mighty armada to defeat England in 1588. As it turned out, none other than Sir Francis Drake was second in command of the English fleet that defeated the Spanish Armada. Drake’s daring exploits gave the English a national hero comparable to Admiral Nelson or King Alfred, and rightly so, he loved England and fought her enemies with courage, daring and style.

References

McCoy, R.M. On the Edge: Mapping North America’s coasts. New York: Oxford University Press. 2012.

Morison, Samuel E. The European discovery of America: The southern voyages. New York: Oxford University Press. 1974

Whitfield, Peter. Sir Francis Drake. New York: New York University Press. 2004