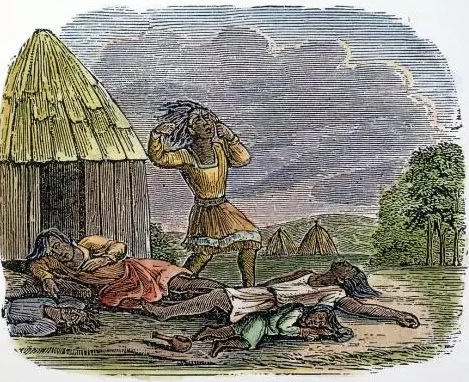

Native Americans: smallpox. Artist, Granger, 1853. Fine Art America.

Native Americans: smallpox. Artist, Granger, 1853. Fine Art America. Roger McCoy

The story of the Columbian Exchange (Explorer’s Tales, 8/1/2015) covered various transfers of crops, animals, and diseases in both directions between the Old World and the New. Of these exchanges smallpox deserves more elaboration because of its profound effect on the outcome of the European venture into the New World. The other diseases included influenza, typhus, measles, whooping cough, diphtheria, and tuberculosis, but smallpox was by far the most deadly.

Smallpox was introduced at numerous points in the New World, but the first was in 1493 when Columbus made his second voyage. This expedition consisted of a fleet of seventeen ships carrying 1,200 men and enough supplies to establish permanent colonies on the island of Hispaniola, which today contains the nations of Haiti and Dominican Republic. Among this large contingent were a few smallpox carriers.

Britain’s first Medical Officer of Health, John Simon, wrote a 1857 report on smallpox. He said, “...smallpox epidemics, concurred with sword and famine to complete the decimation of the native Taino population in Hispaniola. Then moving to Mexico, it even surpassed the cruelties of conquest, suddenly smiting down 3,500,000 and leaving none to bury them.” The estimates of total population and numbers of dead vary widely and their accuracy is uncertain, but they consistently show devastating losses of 50% to 90% during each of several smallpox epidemics in the New World during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These enormous losses meant a shortage of labor for tending crops and working the silver and gold mines. This labor shortage was in fact an early incentive for the Spanish to bring slaves from Africa to the Caribbean colonies as early as 1503. Some Africans had immunity but a few carried the disease and helped spread it.

When explorers arrived they had the advantage of superior weapons and tools, not to mention the novelty of their many accoutrements, armor, horses, and guns. The potential disadvantage for Europeans was their small numbers relative to the indigenous people. If the native people sensed an impending hostile takeover they could sometimes overwhelm the small number of invading Europeans.

When Hernán Cortés first tried to conquer the Aztecs in 1519 he had 600 men but was defeated and escaped with only a third of his army (Explorer’s Tales, 5/3/2015). It is possible his army carried the smallpox to Mexico for when he returned in 1520 they defeated Aztec defenders whose numbers had been already reduced by smallpox. The entire Aztec population was reduced by half, or more, and the survivors were demoralized by this mysterious illness that killed them but appeared to spare the seemingly invincible invaders. Francisco Pizarro had a similar experience in Peru. He was defeated twice in efforts to conquer the Incas of Peru, but was successful the third time in 1531 following a smallpox epidemic.

The Incan empire covered an immense area including Peru, Ecuador, much of Bolivia, northern Chile, and Argentina, with the Andean city of Cuzco, Peru as the administrative center. The empire’s population was estimated to be as high as sixteen million. They had an excellent network of roads, enabling them to assemble and large army to repel intruders. So how could a small army conquer such a place? There are many parts to the answer, including superior weapons, armor, and cavalry. The Spaniards in their steel armor mounted on horseback seemed invincible against the weaker weapons in the hands of Incan foot soldiers. The Incan culture was so strongly focused on their god-like absolute monarch, that when Pizarro captured and killed Atahualpa the power structure collapsed in the Incan empire. Even these advantages might not have been sufficient against the massive Incan army if not for the ravages of smallpox that invaded the Incas prior to Pizarro’s third attempt in 1531.

The smallpox virus had been transmitted to Peru overland from Mexico and reached Cuzco in 1524, six years before Pizarro arrived. The disease had killed the ruler and his son, causing turmoil and ultimately a civil war to determine the successor. An estimated 200,000 people died from the disease and an additional number from the civil war. In the midst of this weakened population Pizarro arrived with only 600 men. He easily defeated the Incan defenders, executed their leader, and assumed full control by 1533.

Smallpox epidemics again struck Peru in 1558 and 1585. One witness account described the horrible results: “They died by scores and hundreds. Villages were depopulated. Corpses were scattered over the fields or piled up in the houses. The fields were uncultivated, the herds untended. Many escaped the foul disease, only to be wasted by famine.”

European fishermen off the coast of North America are believed to have made contact with native people and initiated smallpox in that region. By the time Spanish explorers entered the present day South Carolina area they found many empty villages. In North America smallpox moved from tribe to tribe preceding the arrival of Europeans. Population estimates suggest there were more than 20 million Native Americans in North America in the early seventeenth century. By the end of that century the population was reduced in some areas by as much as 90%. Some entire tribes and their culture disappeared. When the Pilgrims came to Massachusetts in 1620 they found the area around Plymouth very sparsely populated. A smallpox epidemic had preceded them by two years and killed almost 90% of the native population along the Massachusetts coast. That particular epidemic is believed to have spread from French settlements in Nova Scotia. Similar disasters occurred as the disease spread westward in North America, usually occurring before the arrival of Europeans in an area.

When Hernando de Soto marched through the area now called the southeast United States in 1540-41 he found some Indian villages completely abandoned. It is believed they had been vacated two years earlier because of a smallpox epidemic transmitted from coastal Indians to the interior Indians living along the Mississippi Valley. The most highly organized group in North America, the Mississippian Culture, virtually disappeared from the Mississippi River region before Europeans ever made their first settlement in that area.

Colonists in New England regarded smallpox among the Indians as a gift from God. One Puritan clergyman wrote, “The Indians began to be quarrelsome concerning the land they sold to the English, but God ended the controversy by sending the smallpox amongst the Indians. Whole towns of them were swept away, in some of them not so much as one Soul escaping the destruction.” Many colonists praised God for bringing smallpox. With the native population gone or greatly weakened the colonists could help themselves to land and resources. There are documented instances of colonists presenting the local tribes with blankets that had been used by smallpox victims.

History might have taken quite a different course if diseases had not come with the arrival of Europeans at a time when no one understood how diseases were contracted and spread. It is hard to know the full effect of disease during the Columbian Exchange, except that it was very great. Hence smallpox had a particularly lasting influence on the history of the New World.

Sources

Diamond, Jared. Guns, germs, and steel: The fates of human societies. New York: Norton & Company. 1997.

Glynn, Ian & Jennifer. The life and death of smallpox. London: Profile Books. 2004.

Peters, Stephanie True. EPIDEMIC! Smallpox in the New World. New York: Benchmark Books, 2005.