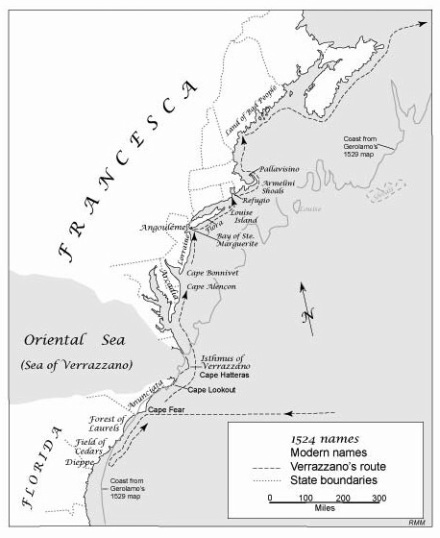

Verrazzano's route in 1524

Verrazzano's route in 1524 Roger M.McCoy

In the fifty years after 1492, explorers sailed northward along the east and west coasts of North America. The Spanish focussed on islands and mainland coasts along Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, then up the west coast as far as Cape Blanco in today’s Oregon. King Henry VII sent John Cabot to the north where he claimed Newfoundland and everything beyond. Francis the First sent Giovanni Verrazzano to find land and wealth for France. He acquired everything between Florida and Newfoundland. Fifty years after Columbus’s first venture, the basic outline of North America began to appear on maps and it resembled a long-stemmed, lopsided goblet.

France almost became an earlier, much bigger player in North America by Verrazzano claiming the east coast from Georgia to Newfoundland, and the U.S.A. might then have been named Francesca. France had all that but dropped it. How did this happen?

In 1524 a Florentine mariner named Giovanni Verrazzano sailed under the auspices of King Francis the First. His objective was to search the last unexplored area in the midlatitudes of North America hoping to find a passage through the immense land mass that stood between Western Europe and Asia. People of that time were convinced, through hopeful thinking, that a water passage must exist.

Verrazzano started with four ships, but by the time they reached the Portuguese island of Madeira, storms had reduced them to only one. Thus Verrazzano sailed ahead unescorted in the Dauphine, a caravel with a crew of fifty men. They made first landfall roughly near present day Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, sailed south along the coast about 150 miles, then turned and began a northward voyage up the east coast of North America, naming every feature. Verrazzano stopped at a few locations along the way to take on fresh water and firewood and attempt to meet the native people.

The remarkable aspects of Verrazzano’s voyage include features he missed, as much as what he found. One big omission was sailing right past Chesapeake Bay without reporting it. Almost certainly he would have investigated such an attractive possible passage. Perhaps bad weather occurred at the time he passed the area, making visibility bad.

As Verrazzano sailed past Pamlico Sound, he declared it to be the Oriental Sea making a connecting passage to Asia. Pamlico Sound, North Carolina is actually an immense lagoon some eighty miles long and varying from fifteen to thirty miles wide. Considering that Verrazzano kept his course well off shore as a precautionary measure, it is not too surprising that he thought the sound was actually a connection to the ocean. Historian Samuel E. Morison flew offshore in a small airplane and determined that an observer on a ship in that position could not have seen the low-lying land west of Pamlico Sound.

It is easy to imagine Verrazzano’s excitement at seeing what he thought would be the all-important passage. For some reason, however, he did not send a few men in a boat to check it more closely. My guess is that he could find no secure anchorage where the ship would be safe while the area was explored in detail. The location is Cape Hatteras, which is known today for its dangerous shoals, currents, and shipwrecks. There is no bay for safe anchorage, and the Dauphine would have had to anchor in open water where the strong flow of the Gulf Stream could have dragged the anchor. All things considered, Verrazzano probably made a wise decision.

The imaginary Oriental Sea, sometimes called the Sea of Verrazzano, gave Verrazzano a strong selling point in support of a second voyage. The “sea” appeared on two maps published soon after the voyage, and continued appearing on maps until the eighteenth century. Mistaken maps influenced subsequent cartographers for a long time, especially when the mistake shows everyone something they hope is true.

An important real feature that Verrazzano found and reported was a very large “beautiful lake about three leagues in circumference” known today as New York Bay. He anchored the Dauphine on the north side of the Verrazzano Narrows, led a landing party into the bay by boat, and was met by many natives in canoes who were eager to meet and trade. Verrazzano described the land and the people in the most glowing terms and described a perfect place for supporting settlement with abundant timber and fertile soils. Unfortunately, before they even reached the shore a sudden strong storm forced them back to the Dauphine. He wrote, “we were forced to return to the ship, leaving the land with much regret on account of its favorable conditions and beauty.” New York Bay was not revisited after the storm, rather they sailed on and found another attractive anchorage at Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. Here they stopped for two weeks of much needed rest, probably near the present site of Newport, Rhode Island. Natives of the Wampanoag tribe welcomed the crew, played ball games with them and showed them the local area.

After this pleasant interlude, the voyage resumed with no further stops except for wood and water. They rounded Cape Cod, crossed Cape Cod Bay, and continued northward until they reached the latitude known to have been reached by John Cabot in 1497. Along the Maine coast they attempted to trade with natives of the Abnaki tribe. The Abnakis would not allow Verrazzano’s men to come ashore, and would only trade by lowering baskets from a cliff for an exchange of goods. Verrazzano wrote in his report to the king, “The people [ Abnakis] were quite different from the others...these were full of crudity and vices, and were so barbarous that we could never make any communication with them.” Probably European fishing ships had already reached this area with some bad results. As Verrazzano’s men rowed away, the Abnakis on the bluff “made all the signs of scorn and shame that any brute creature would make… and they shot at us with their bows.” I would bet “scorn and shame” consisted of mooning, which is an ancient and cross-cultural expression of contempt. Verrazzano no doubt had to restrain the sailors from firing an avenging shot from the falconet attached to the ship’s rail. After this episode, Verrazzano named the Maine coast Land of the Bad People.

Despite Verrazzano’s fantasy about Pamlico Sound being an arm of the Oriental Sea, he actually proved that North America is a continuous land mass from the tropics to the Arctic. This was discouraging news to kings and merchants hoping for a passage to China and India. To make matters worse, Verrazzano brought back no hint of gold, silver, or any forms of immediate wealth.

He hoped to arouse interest in another voyage to investigate his supposed passage, but Francis the First was totally embroiled with war against the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. Therefore, Francis needed much money and all available ships to support his ongoing squabbles. As a result Verrazzano did not return as an explorer, and France did not follow up on the territorial claim that Verrazzano so flatteringly named Francesca. Ten years later, in 1534, Francis again decided to explore the New World, but he showed no further interest in Francesca, instead he sent Jacques Cartier [Verrazzano was dead by this time] to the lands around the St Lawrence River.

So what became of Verrazzano? He returned to a less glamorous, but more lucrative life as a mariner merchant collecting brazilwood (used for red dye) from South America and the Caribbean islands. On his third such voyage in 1528, he and six sailors met a sudden, bloody death on a Caribbean beach during a brief encounter with Carib cannibals while their helpless shipmates offshore watched from the ship.

References

McCoy, Roger M., On the Edge: Mapping North America’s Coasts, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Morison, Samuel E. The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages, New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Wroth, Lawrence C., The Voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano: 1524-1528, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970.

In the fifty years after 1492, explorers sailed northward along the east and west coasts of North America. The Spanish focussed on islands and mainland coasts along Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, then up the west coast as far as Cape Blanco in today’s Oregon. King Henry VII sent John Cabot to the north where he claimed Newfoundland and everything beyond. Francis the First sent Giovanni Verrazzano to find land and wealth for France. He acquired everything between Florida and Newfoundland. Fifty years after Columbus’s first venture, the basic outline of North America began to appear on maps and it resembled a long-stemmed, lopsided goblet.

France almost became an earlier, much bigger player in North America by Verrazzano claiming the east coast from Georgia to Newfoundland, and the U.S.A. might then have been named Francesca. France had all that but dropped it. How did this happen?

In 1524 a Florentine mariner named Giovanni Verrazzano sailed under the auspices of King Francis the First. His objective was to search the last unexplored area in the midlatitudes of North America hoping to find a passage through the immense land mass that stood between Western Europe and Asia. People of that time were convinced, through hopeful thinking, that a water passage must exist.

Verrazzano started with four ships, but by the time they reached the Portuguese island of Madeira, storms had reduced them to only one. Thus Verrazzano sailed ahead unescorted in the Dauphine, a caravel with a crew of fifty men. They made first landfall roughly near present day Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, sailed south along the coast about 150 miles, then turned and began a northward voyage up the east coast of North America, naming every feature. Verrazzano stopped at a few locations along the way to take on fresh water and firewood and attempt to meet the native people.

The remarkable aspects of Verrazzano’s voyage include features he missed, as much as what he found. One big omission was sailing right past Chesapeake Bay without reporting it. Almost certainly he would have investigated such an attractive possible passage. Perhaps bad weather occurred at the time he passed the area, making visibility bad.

As Verrazzano sailed past Pamlico Sound, he declared it to be the Oriental Sea making a connecting passage to Asia. Pamlico Sound, North Carolina is actually an immense lagoon some eighty miles long and varying from fifteen to thirty miles wide. Considering that Verrazzano kept his course well off shore as a precautionary measure, it is not too surprising that he thought the sound was actually a connection to the ocean. Historian Samuel E. Morison flew offshore in a small airplane and determined that an observer on a ship in that position could not have seen the low-lying land west of Pamlico Sound.

It is easy to imagine Verrazzano’s excitement at seeing what he thought would be the all-important passage. For some reason, however, he did not send a few men in a boat to check it more closely. My guess is that he could find no secure anchorage where the ship would be safe while the area was explored in detail. The location is Cape Hatteras, which is known today for its dangerous shoals, currents, and shipwrecks. There is no bay for safe anchorage, and the Dauphine would have had to anchor in open water where the strong flow of the Gulf Stream could have dragged the anchor. All things considered, Verrazzano probably made a wise decision.

The imaginary Oriental Sea, sometimes called the Sea of Verrazzano, gave Verrazzano a strong selling point in support of a second voyage. The “sea” appeared on two maps published soon after the voyage, and continued appearing on maps until the eighteenth century. Mistaken maps influenced subsequent cartographers for a long time, especially when the mistake shows everyone something they hope is true.

An important real feature that Verrazzano found and reported was a very large “beautiful lake about three leagues in circumference” known today as New York Bay. He anchored the Dauphine on the north side of the Verrazzano Narrows, led a landing party into the bay by boat, and was met by many natives in canoes who were eager to meet and trade. Verrazzano described the land and the people in the most glowing terms and described a perfect place for supporting settlement with abundant timber and fertile soils. Unfortunately, before they even reached the shore a sudden strong storm forced them back to the Dauphine. He wrote, “we were forced to return to the ship, leaving the land with much regret on account of its favorable conditions and beauty.” New York Bay was not revisited after the storm, rather they sailed on and found another attractive anchorage at Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. Here they stopped for two weeks of much needed rest, probably near the present site of Newport, Rhode Island. Natives of the Wampanoag tribe welcomed the crew, played ball games with them and showed them the local area.

After this pleasant interlude, the voyage resumed with no further stops except for wood and water. They rounded Cape Cod, crossed Cape Cod Bay, and continued northward until they reached the latitude known to have been reached by John Cabot in 1497. Along the Maine coast they attempted to trade with natives of the Abnaki tribe. The Abnakis would not allow Verrazzano’s men to come ashore, and would only trade by lowering baskets from a cliff for an exchange of goods. Verrazzano wrote in his report to the king, “The people [ Abnakis] were quite different from the others...these were full of crudity and vices, and were so barbarous that we could never make any communication with them.” Probably European fishing ships had already reached this area with some bad results. As Verrazzano’s men rowed away, the Abnakis on the bluff “made all the signs of scorn and shame that any brute creature would make… and they shot at us with their bows.” I would bet “scorn and shame” consisted of mooning, which is an ancient and cross-cultural expression of contempt. Verrazzano no doubt had to restrain the sailors from firing an avenging shot from the falconet attached to the ship’s rail. After this episode, Verrazzano named the Maine coast Land of the Bad People.

Despite Verrazzano’s fantasy about Pamlico Sound being an arm of the Oriental Sea, he actually proved that North America is a continuous land mass from the tropics to the Arctic. This was discouraging news to kings and merchants hoping for a passage to China and India. To make matters worse, Verrazzano brought back no hint of gold, silver, or any forms of immediate wealth.

He hoped to arouse interest in another voyage to investigate his supposed passage, but Francis the First was totally embroiled with war against the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. Therefore, Francis needed much money and all available ships to support his ongoing squabbles. As a result Verrazzano did not return as an explorer, and France did not follow up on the territorial claim that Verrazzano so flatteringly named Francesca. Ten years later, in 1534, Francis again decided to explore the New World, but he showed no further interest in Francesca, instead he sent Jacques Cartier [Verrazzano was dead by this time] to the lands around the St Lawrence River.

So what became of Verrazzano? He returned to a less glamorous, but more lucrative life as a mariner merchant collecting brazilwood (used for red dye) from South America and the Caribbean islands. On his third such voyage in 1528, he and six sailors met a sudden, bloody death on a Caribbean beach during a brief encounter with Carib cannibals while their helpless shipmates offshore watched from the ship.

References

McCoy, Roger M., On the Edge: Mapping North America’s Coasts, New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Morison, Samuel E. The European Discovery of America: The Northern Voyages, New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Wroth, Lawrence C., The Voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano: 1524-1528, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1970.