Ship ready for winter. W. W. May artist. Scott Polar Institute.

Ship ready for winter. W. W. May artist. Scott Polar Institute. In 1819 the British navy sent Lieutenant William E. Parry into the Arctic with the intention of finding the Northwest Passage and sailing through to the west end. Two ships, the Griper and Hecla expected to stay through the winter. Until that time no expedition had purposely wintered in the Arctic and all voyages had returned home when sea ice began to form.

One major technological innovation made such over-wintering possible for the navy: food preservation by canning. In 1810 a Frenchman, Nicolas Appert, discovered that food cooked in a sealed jar or canister did not spoil. Appert won a well-deserved 12,000 francs for his discovery, and the English firm, Donkin, Hall, and Gamble, immediately adopted the idea and began canning food under contract for the Royal Navy. This new discovery, canned food, changed everything. Now ships could explore the Arctic water for two consecutive seasons or more without having to return home between summers.

Wintering, however, required some additional innovations regarding outfitting and supplying the ship and, more importantly, keeping idle crews occupied during the seven to nine-month period while the ship was bound in ice. Lieutenant William E. Parry’s expedition was the first to develop the routine which became common practice for future expeditions.

Outfitting the ships was the first priority. They devised heat ducts to distribute heat from a central coal stove throughout the ship, and lined the inside surface of the hull with cork for insulation. They built a system to draw in fresh air and exhaust stale air. This was especially necessary to prevent build-up of water vapor and resulting condensation in the living quarters. Snow was melted in tanks surrounding the flue to produce a steady supply of water for cooking, washing, and drinking. All these modifications provided comfortable living quarters through the worst of the Arctic winter.

During an expedition in 1850 Lieutenant Osborn wrote: “Fancy the lower deck and cabins of a ship, lighted entirely by candles and oil lamps; every aperture by which external air could enter secured, and all doors doubled to prevent draughts. It is breakfast time and reeking hot cocoa from every mess table is sending up a dense vapor, which, in addition to the breath of so many souls, fills the space between decks with mist and fog. Should you go on deck, and go from 50° above zero to 40° below in eight short steps, a column of smoke will be seen rising through certain apertures, whilst others are supplying a current of pure air.”

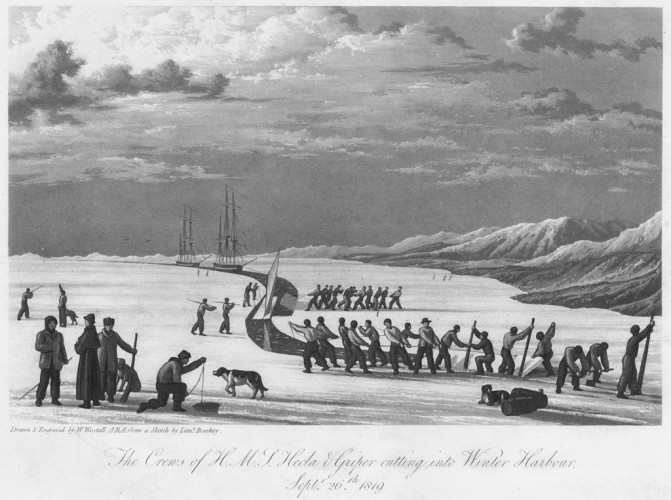

The ships had to find a protected inlet away from the path of moving crushing ice floes. The above illustration by Lieutenant Parry shows crews of the Griper and Hecla cutting a channel into a bay for the winter of 1819-20. Once in position for the winter the ships quickly became icebound. The crew then enclosed the deck with canvas, forming a large tent as protection against snow and wind, and providing a place for exercise in bad weather. Snow was banked around the hull, adding insulation as shown in the second illustration by Lieutenant W. W. May on a later expedition.

Winter activities for the officers involved daily scientific measurements of snow, wind, ice, temperature, and the earth’s magnetic field. Such measurements taken by subsequent expeditions throughout the nineteenth century created a benchmark of data for comparison by scientists today. Occasional hunting parties supplemented the ship’s rations with meat from caribou and musk ox. Most of the time, however, no game could be found. Parry wrote that there were few animals available due to the migration farther south. Occasionally they would see Arctic foxes or wolves, but most of the time nothing moved in the silence of the long winter, which Parry called “a death-like stillness.”

“Officers inspected the men,” Osborn wrote, “and every part of the ship to see if both were clean, and then they dispersed to their several duties, which at this severe season were very light; indeed confined mainly to supply snow to melt for water, and keeping the fire-hole in the ice open [for water in the event of fire].”

In addition to the daily cleaning and maintenance performed by the crew, the men attended daily classes to learn reading and writing. Officers taught the mostly illiterate crew to read the Bible and reported how pleased the men were with themselves that they could return to their homes as readers. Sherard Osborn wrote, “There, on wooden stools, leaning over the long tables, were a row of serious and anxious faces, tough old marines curving ‘pothooks and hangers’ [learning to write the letters] as if their very lives depended on it. Then some big-whiskered scholar top-man [sail rigger], with slate in hand, recites his multiplication-table, and grins approval.” This education, while good for the men, also kept them from the boredom and discontent of idleness. “Monotony was our enemy,” said Osborn. “Men who had no source of amusement—such and reading, writing, or drawing—were much to be pitied. ...nothing struck one more than the strong tendency to talk of home and England; it became quite a disease. We spoke as if all the most affectionate husbands and dutiful sons had found their way into this Arctic expedition.”

Osborn wrote, “If it was school night, the pupils went to their posts, artists painted, some played cards or chess combined with conversation and an evening’s glass of grog [a mixture of rum and water], and a cigar or pipe served to bring round bedtime again.” For their part, the officers performed plays and played musical instruments to entertain the crew. Some dressed as women to play female roles, and the crew took great amusement to see their officers in silly costumes and playing comical roles.

A later phase of exploration by the Royal Navy turned to winter overland treks by sled, either man or dog drawn. This activity began when they realized that much could be explored on foot while the sea was frozen, providing an easy avenue of travel. Exploration on foot began as soon as the first glimmer of daylight ended the constant darkness of winter in late January or early February, and continued until thawing began when neither sea nor land could be traversed on foot.

Occupying the crew with education was a brilliant idea, serving as a positive mental activity and also giving the men skills that strengthened their self-esteem. Keeping an ice-bound crew busy, both creatively and intellectually, was essential to the success of such a voyage.

References

McCoy, Roger M. On The Edge: Mapping the Coasts of North America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Osborn, Sherard. Stray Leaves From an Arctic Journal: Eighteen Months in the Polar Regions in Search of John Franklin’s Expedition, in the Years 1850-51. New York: George Putnam,1852.

Parry, W. E. Journal of a Second Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage. London: John Murray, 1824.