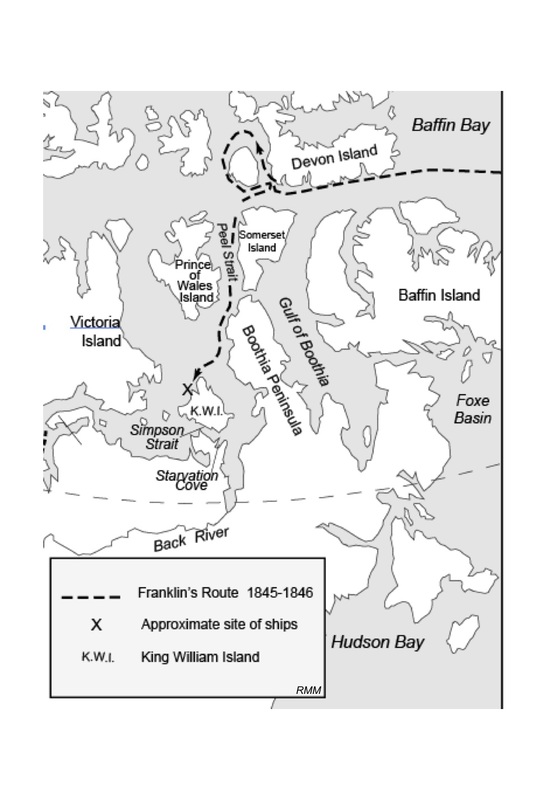

Recap: In 1857, twelve years after the expedition left England, the relentless Lady Jane Franklin sent M’Clintock to search for her husband, Sir John Franklin, near King William Island.

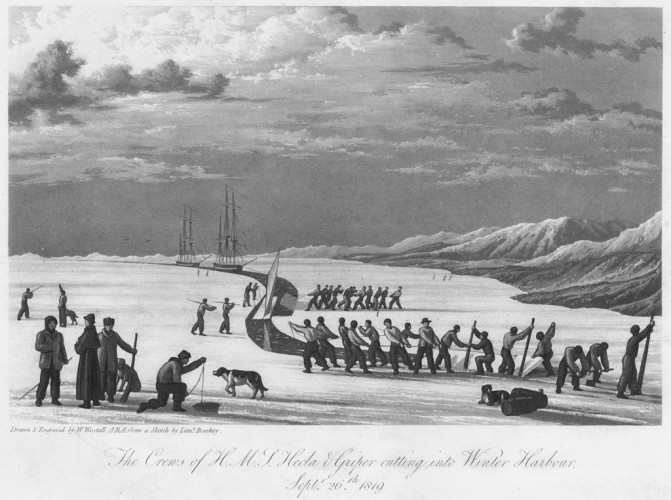

M’Clintock’s expedition split into two parties taking different routes toward King William Island. Each party consisted of teams of six to eight men harnessed to heavy sledges, each loaded with eight hundred pounds of cargo. They could average ten or twelve miles per day over the relatively smooth surface of the frozen sea and go where no ship could sail.

Eventually M’Clintock’s party came upon a rock cairn containing this ominous message:

April 25, 1848 — H. M. ships, Terror and Erebus were deserted on the 22nd April 5 leagues N.N.W. of this, having been beset since 12th September, 1846. The officers and crews consisting of 105 souls, under the command of F. R. M. Crozier, landed here. Sir John Franklin died on the 11th June, 1847; and the total loss by deaths in the expedition has been to this date 9 officers and 15 men.

F. R. M. Crozier James Fitzjames

Captain and Senior Officer Captain H. M. S. Erebus.

start tomorrow, 26th, for Back’s Fish River.

Apparently Captain Crozier, who took command when Franklin died, had abandoned the expedition and tried to take his 105 starving men to a place of refuge. The nearest such destination was a Hudson Bay Company post on the Great Slave Lake, more than 1,000 miles away. The company of the Erebus and Terror must have been on reduced rations for much of the winter of 1847-48, and the men already wasted enough to be in weakened condition before they left the ships.

Traveling along the west coast of King William Island, M’Clintock found relics of the expedition, including a twenty-eight foot boat mounted on a sledge that the escaping men had brought only a short distance. A large quantity of tattered clothing lay in the boat, and portions of two human skeletons. The boat weighed about eight hundred pounds and when mounted on the heavy sledge made a 1,400 pound dead weight for the weakened men to pull. Sledging with such an incredible weight went against all that had been learned up to that time about travel in the Arctic where survival depended upon traveling light. Besides the provisions they could muster, the survivors had carried almost anything of value, including silver table service and an “amazing quantity of clothing”—of no use to their survival.

Other items found in the boat included five watches, two double-barreled guns— one barrel in each of them was loaded and cocked. Several small books were found, including The Vicar of Wakefield, and scriptural or devotional readings. A brief listing of the items M’Clintock found serves to illustrate their seeming lack of awareness of the dire situation they faced. He saw different types of boots, such as sea boots, cloth winter boots, heavy ankle boots, shoes, silk handkerchiefs, towels, soap, toothbrushes, and combs. Other items included twine, nails, saws, files, bristles, wax ends, sailmakers’ palms, powder, bullets, shot, cartridges, knives (including dinner knives), needle and thread cases, and two rolls of sheet lead. The guns, bullets, powder, and hunting knives would have been essential if they found game. M’Clintock found a bit of tea and forty pounds of chocolate but no biscuits or meat. Also in the boat were eleven large silver spoons, four silver teaspoons, and eleven silver forks, all bearing crests of Franklin or one of the other officers, but no iron spoons of the type issued to seamen. Apparently desperation forced the men to abandon the heavily loaded sledge and continue only with what they could carry.

The emerging story from M’Clintock and various later accounts remains hazy, but certain elements are firm. One hundred five men from the two ships had set off for the Great Slave Lake via Back River. As they reached Terror Bay, only twenty-five miles from their abandoned ships, the crewmen, weak from hunger and scurvy, had already begun to falter under their heavy loads. They apparently camped for several days to recuperate. Later searchers found several skeletons and two boats in addition to the one found by M’Clintock. Physical evidence suggests that Captain Crozier and any men strong enough to move continued south toward the Back River. As the group slowly moved along the south coast of King William Island, fallen men and abandoned equipment marked their route. At some point the group split and took different directions, probably hoping that at least one would reach help. Crozier’s group of about forty men continued toward the Back River. A second group headed east toward Boothia Peninsula, perhaps hoping to reach open water and intercept a rescue ship. Whatever their expectation, they failed and died.

Meanwhile, Crozier’s dwindling party crossed Simpson Strait on the ice and reached the mainland. Sometime, possibly as much as three years later, Eskimos found bodies of thirty men at a small bay on the north coast of Adelaide, now called Starvation Cove. They had traveled nearly one hundred fifty miles from the ships, almost reaching the estuary of the Back River. The Eskimos’ account revealed that the corpses had been eaten by humans. They said that bones had been cut through by saws, and skulls had been broken open to remove the brains. Also, the Eskimos found many papers, probably records of the expedition. Having no value to the Eskimos, the papers were discarded and lost forever.

Franklin’s starving men purposely had avoided contact with Eskimos who could have helped the stranded mariners survive. The crewmen had persisted in living as Europeans who saw no reason to learn from an uncivilized people about living in the Arctic environment. Most British naval explorers of the nineteenth century refused to learn from the experience of other explorers or the Eskimos. Author James Morris attributes this hubris to the success of the British empire in the nineteenth century. He wrote, “...an assumption of superiority was ingrained in most Britons abroad. ...the ancient social orders of the subject nations were all too often ignored or mocked.”

Applying that outlook to the nineteenth century exploration experience in the Arctic shows that the British naval officers failed to recognize an environment in which they could not follow their usual practice of simply transplanting their culture. Few of them ever realized that the indigenous culture held the essential keys to survival in the Arctic.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson described this attitude as part of the culture of the British gentry when he wrote, “Just as with fox hunting for the British gentleman, in which the prime objective is not killing the fox, but the proper observance of form during the pursuit and kill, also, explorations should be done properly and not evade the hazards of the wilderness by the vulgarity of going native. They must face the dangers of the Arctic or other wilderness in the proper manner.” He wrote further “...that the crews of the Erebus and Terror perished as victims of the manners, customs, social outlook, and medical views of their time.”

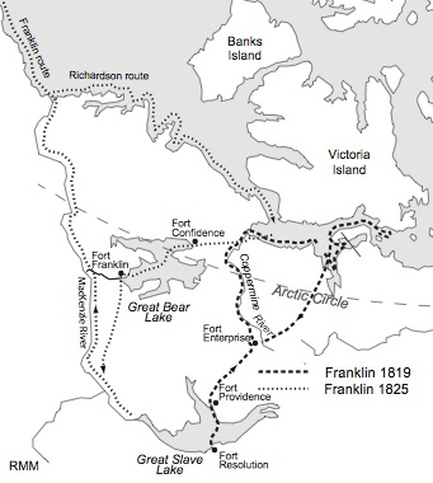

It should be noted that the attitude of exploring the Arctic as “gentlemen,” existed primarily in the Admiralty and among officers of the Royal Navy. The Hudson Bay Company employees, who were also primarily British, survived very well on Arctic expeditions by depending heavily on fundamentals earlier described to the Admiralty by John Rae. Norwegian, Canadian, American explorers, and the voyageurs all coped with the Arctic by following the Eskimo ways. Some Hudson Bay Company employees ridiculed the English naval explorers because of their unwillingness to give up comforts while in the wilderness. The widely known nineteenth century Chief Factor of the HBC, George Simpson, is quoted as saying, “Lieutenant Franklin, the officer who commands the party [referring to Franklin’s first expedition], must have three meals per day, tea is indispensable, and with the utmost exertion he cannot walk above eight miles in one day. It does not follow if these gentlemen are unsuccessful that the difficulties are insurmountable.” Despite these criticisms, the British naval officers’ devotion to duty and acts of heroism were a source of pride to the nation.

The central figure in this saga, Sir John Franklin, is a bit of a paradox. Although his expedition failed, the mystery of his whereabouts elevated him from an ordinary explorer to a revered public idol. This is strange considering that his actual lifetime achievements were of small consequence and his expeditions lost far more lives than all the other Arctic expeditions. Furthermore, a king’s ransom was spent searching for him. Between 1848 and 1859 more than fifty expeditions searched for some sign of Franklin’s ships and men. Other lives and ships were lost during the search. Years were wasted through searching in places not on Franklin’s proposed route and avoiding his planned route because it was filled with ice when the searchers arrived. Search ships were sent to every corner of the Arctic except the one where Franklin went.

A primary force pushing the Admiralty was the intrepid Lady Jane Franklin. She was relentless in her determination to learn what happened to her husband and eventually raised funds herself to send an expedition. In the end it was Lady Jane’s private effort in sending M’Clintock, not the navy, that found remains of Franklin’s expedition and pieced together what had happened. Lady Jane's determination was not to be denied: she refused to accept the Eskimo’s report of cannibalism, contested the Admiralty’s award of the prize money to Commander Robert McClure, and continued to insist that Sir John Franklin had succeeded in finding the Northwest Passage. McClure, however, had entered the passage from the west and had absolutely discovered one of the routes through the passage.

In the summer of 2014 Parks Canada discovered the HMS Erebus sitting upright with masts shorn off in thirty-five feet of water near King William Island. The location was determined with sonar, and divers explored the ship to make positive identification. Underwater investigations continued in the summer of 2015. The HMS Terror is still missing.

Pictures can be seen on the Parks Canada website:www.pc.gc.ca/eng/culture/franklin/index.aspx

The PBS science program NOVA has produced several presentations of the Franklin Expedition., The most recent, Arctic Ghost Ship, was aired on September 23, 2015 and may be viewed on the NOVA website at www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/tech/arctic-ghost-ship.html.

Sources

Berton, Pierre. The Arctic Grail: the Quest for the Northwest Passage and the North Pole, 1818-1909, New York:Viking Penguin, 1988.

McCoy. Roger M. On The Edge: Mapping North America’s Coasts. New York: Oxford University Press. 2012.

Morris, James. Heaven's Command: An Imperial Progress. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1973.

Stefansson, Vilhjalmur. Unsolved Mysteries of the Arctic. New York: Collier Books, 1962.